A June 12 headline in Politico might need some unpacking. It reads: “Sanders goes full FDR in defense of democratic socialism.”

FDR, of course, is Franklin D. Roosevelt, the 32nd president of the United States, in office from 1933 to 1945, leading the nation during the New Deal of the 1930s and then, in the 1940s, to victory in World War II.

Along the way, FDR won four landslide elections, in 1932, 1936, 1940, and 1944. In addition, FDR’s hand-picked successor, Harry Truman, won a fifth national victory in 1948. As such, with those five consecutive victories, FDR’s New Deal coalition amassed the greatest White House win-streak since the 19th century—what vote-hungry politician wouldn’t want a piece of that?

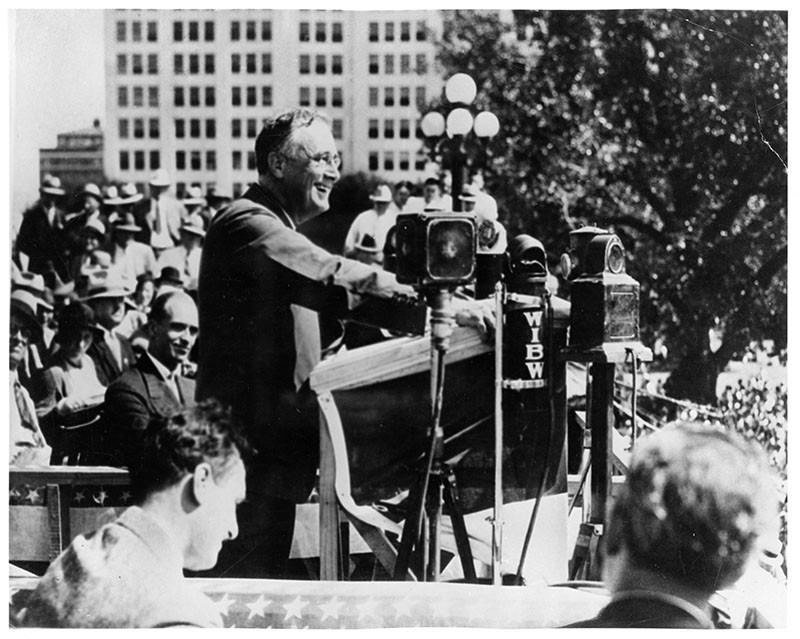

Franklin D. Roosevelt giving a campaign speech to farmers in Topeka, Kansas, promising them a “new deal.” (Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library & Museum)

Moreover, more than seven decades after his death, FDR’s legacy is still felt: For instance, there’s the Social Security program, now an evergreen of governance. And more broadly, there’s the general feeling nowadays that the federal government has a responsibility to oversee the management of the economy—that is, preventing depressions and combatting both extreme poverty and excessive inequality. If it seems hard to imagine an America without such policies in place, well, that just goes to show the depth of FDR’s influence.

Yes, of course, FDR had many fierce critics, in his life and ever since, and yet the continuing popularity of his persona and his ideas is undeniable.

In other words, Bernie Sanders was well advised to stake his claim to Roosevelt’s legacy. In his speech at George Washington University on June 12, Sanders name-checked FDR eight times, arguing that his own proposals are simply an echoing, and an updating, of FDR’s ideas.

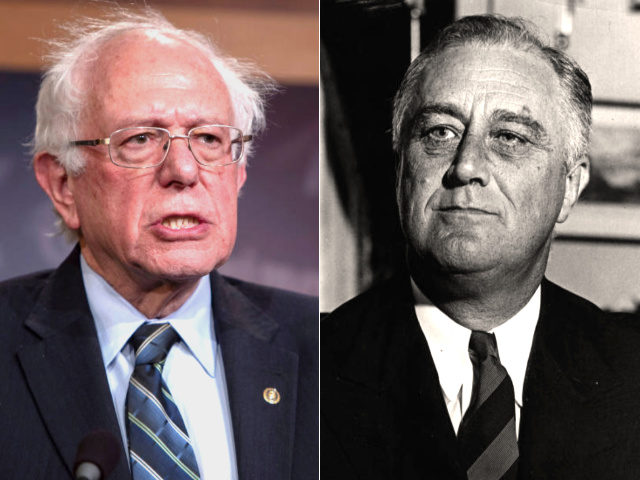

Presidential hopeful Bernie Sanders delivers remarks at George Washington University on June 12, 2019, in Washington, DC. Sanders discussed democratic socialism in his address. (Sarah Silbiger/Getty Images)

In particular, Sanders recalled FDR’s proposal, in his 1944 State of the Union address, for an “economic bill of rights,” covering such topics as wages, education, and health care.

Interestingly, the 32nd president even included this pro-business provision: “The right of every businessman, large and small, to trade in an atmosphere of freedom from unfair competition and domination by monopolies at home or abroad.”

Indeed, in these times of Big Tech domination, such thinking seems fresh and compelling all over again.

Now, 75 years later, Sanders sought to wrap himself in FDR’s mantle as he put forth a “21st century economic Bill of Rights,” including:

The right to quality health care, the right to as much education as one needs to succeed in our society, the right to a good job that pays a living wage, the right to affordable housing, the right to a secure retirement, and the right to live in a clean environment.

If one only looks at the polls on policy, Sanders has a popular package on his hands. For instance, on the issue of securing dignity in retirement, one poll from earlier this year finds that 74 percent of all Americans believe that Social Security should not be cut in any way; moreover, another poll, taken three years ago, finds that 72 percent of Americans support higher taxes on the rich to pay for the expansion of Social Security. And the supporting percentages among just Democrats—the folks who will be picking the 2020 nominee—are even higher.

Yet of course, presidential elections are about more than just policy proposals put down on a piece of paper. The voters also consider questions of personality, character, temperament—and, yes, trustworthiness.

So it’s interesting that within the Democrat primary field, Sanders is polling at less than 17 percent. That’s enough to put him in second place, behind Joe Biden, but still, it means that five-sixths of Democrats are supporting someone else—or no one else.

So what could be undercutting Sanders’ appeal? Why do Democrats not fully embrace Sanders, even when he cites the sainted FDR?

We can point to lots of possible explanations, of course, including the fact that most other Democrats in the race support similar policies, even if they don’t invoke FDR’s name. (Having been born in 1941, Sanders can say that he actually remembers the living FDR.)

President Franklin D. Roosevelt speaking on a platform during his fourth presidential inauguration in September 1944. (Keystone Features/Getty Images)

And yet there’s another, more profound question to be asked about Sanders: Is he being sincere when he claims that he is an FDR man? Or to put the matter more bluntly, Is Sanders, in fact, way to the left of FDR?

We can start to answer such questions by considering self-appellation—that is, the terms that the two men have used to describe themselves.

FDR sometimes called himself a “liberal,” albeit one with some decidedly conservative aspects. For instance, in 1936, Roosevelt traveled to Dallas for the unveiling of a statue honoring Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee, whom FDR described as “one of the greatest American Christians and one of our greatest American gentlemen.”

That same day, speaking at the Cotton Bowl, FDR seemed to embrace what might be called the “Gone With the Wind” view of the Civil War and post-Civil War Reconstruction; as he said to the assembled Texans, “You have gone through the difficult days of the War Between the States and the trials of Reconstruction. You have had to fight against oppression from within and without.”

We know that Roosevelt, a New Yorker, was no fan of the Confederacy. However, he was president of all the 48 states of the union, and so he was judiciously—and, yes, politically—mindful of public sentiment, including conservative and nostalgic sentiment. And so that’s one reason he carried Texas, and all of Dixie, comfortably, in all four of his presidential runs.

Okay, so if we dig into Roosevelt a little bit, we find a complicated picture; FDR was undeniably on the left overall, and yet at the same time, he was always staunchly anti-communist.

As he also said in 1936: “I have not sought, I do not seek, I repudiate the support of any advocate of Communism or of any other alien ‘ism’ which would, by fair means or foul, change our American democracy.”

At the same time, FDR was also cheerleader for Americanism and American nationalism; as he said in yet another speech in 1936, his goal was “a safer, happier, more American America.” Indeed, one might even go so far as to define FDR as an “Economic Patriot.”

As we can see, FDR was nuanced. Yes, he was a liberal, economically, but he was a moderate, and sometimes even a conservative, on cultural issues. And as for winning World War II and bringing America to its zenith of power and influence in the world—where does one put that on the ideological meter?

President Franklin D. Roosevelt reviews a map of an American army camp during his nationwide inspection of war plants and military training centers circa 1943. (Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

We might pause to note that one big fan of FDR was … Ronald Reagan. Yes, the 40th president was a good deal different from the 32nd president, and yet even so, the Gipper retained a lifelong affection for the man he had voted for, four times. In fact, in the White House, RWR happily hosted a centennial tribute to FDR.

Okay, so now, back to Sanders. For openers, he calls himself a “democratic socialist”—that’s a term FDR never used about himself.

Moreover, there’s serious question as to the various ideological places that Sanders has been to in his life, as well as the geographical places he has traveled to, and paid homage to. On both scores, Reason magazine’s Justin Monticello has done valuable spadework:

Sanders once identified as a socialist who, with reservations, admired the economic achievements of Cuba under Fidel Castro, of Nicaragua under the Sandinistas, and of the Soviet Union right up to the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Running for office as a candidate for the Liberty Union Party in Vermont in the 1970s, Sanders sought a top tax rate of 100%, saying “nobody should earn more than $1 million.”

Sanders wanted to stop businesses from moving out of their original communities, arguing that the ultimate solution to protect workers was national legislation that would “bring about the public ownership of the major means of production.” He favored the government seizure of “utilities, banks, and major industries,” without compensation to investors or stockholders.

That’s not FDR-type thinking, that’s a whole different ideology.

Of course, even if he was once a real socialist, or maybe even more than a socialist—Brooklyn in the ’40s was, after all, known for its many “red diaper babies”—Sanders has a right to change his mind. Yes, it’s possible that when he was younger, he was way-y-y to the left—way to the left of the New Deal—and that he’s mellowed into, merely, a staunch progressive.

Or, it’s possible that when Sanders invokes FDR, he’s seeking to mislead us, and that, in fact, those hard-left flames still burn bright in his heart. (That might explain why he always seems so cranky.)

At a minimum, Sanders owes us a full accounting of his shifting views—and how, why, and where they have changed.

And of course, the rule is always, to borrow a Russian proverb, Доверяй, но проверяй. Translated, that’s “trust, but verify.”

Maybe Sanders already knows that.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.