Americans will face a divided government in 2019, with Democrats controlling the U.S. House, and Republicans in charge of the Senate and the White House.

And the confrontation has already begun.

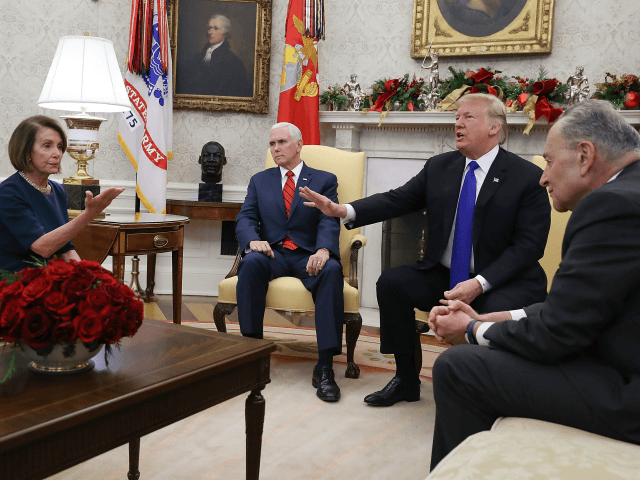

Democrats refuse to yield to President Donald Trump’s demand for $5 billion in funding for a border wall, or fence — a down payment on the estimated $25 billion cost to secure the entire U.S.-Mexico border.

They are holding out because they are convinced that Trump will cave — just as every Republican before him has caved, just as he himself caved before rather than be blamed for a government shutdown.

Meanwhile, Republicans are increasingly convinced that Trump will stand his ground — largely because he has no other choice.

When it looked like he might compromise earlier this month, and sign a continuing resolution without border wall funding, conservatives reacted in alarm, reminding him that he would be reneging on a core campaign promise and suggesting he would lose their support.

He is backed into a corner: he cannot yield. He has to fight.

In negotiation, the side that is too weak to compromise is, ironically, in a stronger bargaining position. Democrats may have made a fateful miscalculation.

But they may also have tied their own hands by promising that they will never compromise on the wall. “You’re not getting your wall today, next week, or on January 3 when Democrats take control of the House,” Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) said on the Senate floor last week.

There are only two reasons to think there might be a compromise. One is that Democrats have supported border security before — in the form of a “fence,” not a “wall.” Two of the eight “wall” prototypes are fences anyway, meaning both sides might accept funding for a “fence”.

The other is that Pelosi will have more flexibility once she is elected Speaker of the House; until then, she has to take a hard line to keep her caucus’s new radicals on board.

Such are the calculations in a divided government.

It is an identical political scenario to that of 2011, after the Tea Party wave. And just as Republicans believed that victory would be a prelude to defeating President Barack Obama in 2012, Democrats hope to build on their 2018 successes to oust President Trump — at the ballot box or otherwise.

It is interesting to consider how Obama confronted the new political challenge. Early in 2011, then-Secretary of the Treasure Timothy Geithner sent new Speaker of the House John Boehner (R-OH) a letter warning him to raise the debt limit, lest the country default on its debts.

It was a curious warning, since while Republicans had run against massive government spending, few Republicans had made the debt limit a major issue.

Geithner’s letter provoked a confrontation with the Republican-led House that resulted in a political crisis that summer. It was resolved, ultimately, in the Budget Control Act of 2011, which raised the debt limit in return for automatic spending cuts (the “sequester”) in the event that the parties refused to accept the recommendations of a new debt commission. The spending cuts fell equally on defense spending and domestic discretionary programs.

In the long term, the effect was nil. Obama rejected the debt commission’s prescriptions, as did the Republicans. The sequester kicked in for a while, briefly limiting the growth of federal spending, but was gradually removed.

What the confrontation did accomplish, however, was what Obama had likely intended: to convince the public that Republican control was too dangerous to risk. He went on to win re-election easily in 2012.

President Trump could repeat Obama’s strategy. He could look for opportunities to fight the new Democrat-run House, exposing how radical the opposition has become under the influence of “democratic socialists.”

Just as Obama played on class divisions to encourage the “99%” to oppose the “1%,” Trump could exploit differences on wedge issues like immigration — a task Democrats have made easier in the current fight over border wall funding.

But there is no guarantee such confrontation will work for Trump in 2020 as it did for Obama in 2012. Obama, after all, had the entire mainstream media and Hollywood behind him, while Trump is their public enemy number one. The public is also tired of divisive rhetoric, even though Trump is largely fighting back.

The alternative is for Trump to look for opportunities to cooperate. He could find areas of bipartisan agreement — as he did recently on prison reform — and offer Democrats the opportunity to work together.

He could play up his skills as a dealmaker, and present himself in the 2020 election as the only candidate who can bring the parties together to produce solutions to the nation’s urgent problems.

The risk of that strategy is that Trump might alienate some of his core supporters if he attempts a Bill Clinton-like triangulation, or an Arnold Schwarzenegger-style conversion.

But as long as he holds firm on the policy priorities most important to his base — especially border security — Trump will have flexibility to negotiate on other issues.

Meanwhile, Trump can still make the most of his executive powers by appointed conservative judges to the federal bench and reforming far-left policies in federal agencies.

That will mean more confrontations — even as Trump strives to achieve legislative cooperation.

If we are lucky, 2019 will be a year of both.

Joel B. Pollak is Senior Editor-at-Large at Breitbart News. He is a winner of the 2018 Robert Novak Journalism Alumni Fellowship. He is also the co-author of How Trump Won: The Inside Story of a Revolution, which is available from Regnery. Follow him on Twitter at @joelpollak.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.