“Populism” has become a favored expression in dealing with contemporary politics. Like many of the terms employed by political journalists, it has no specific definition. Unlike the formal sciences, political, and social science invoke and employ terms having only tentative discursive or lexical definition—usually framed as criterial definitions in which some properties are advanced as definitive of the concept. Thus, we are told that “populism” refers to a political strategy calculated to address the felt needs of the general population as distinct from, and usually opposed to, the settled preferences of the “establishment.”

Such a definition is so loosely framed that it can be applied to almost any significant variation in customary politics. Thus we are informed that V. I. Lenin, Benito Mussolini, and Adolf Hitler all were “populists”—as were Mao Zedong, Fidel Castro, and Pol Pot. As such, the term means little more than “revolutionary.” We are now told that the current president of the United States, as a populist, is somehow a member of such a list. We are assured that like Mussolini, President Donald J. Trump is a “fascist.”

Intelligent persons tell us that all this is very serious—but fail to offer a supporting analysis. At best, such a claim is preliminary, heuristic, and research suggestive. What is needed is an “unpacking” of the concept of “populism”—to demonstrate the substantive similarities between the populisms of Mussolini and Trump. That minimally requires the provision of an applicable historic context and measurable specifics.

We are provided some assistance in that regard when we are told that, as president of the United States, one of the first foreign politicians Trump chose to meet was Nigel Farage, leader of the United Kingdom Independence Party. Both populists—each in his own country—addressed themselves to what each conceived was a neglected audience and potential constituency: domestic nationalists and traditionalists. Their opponents were, and are, the politically liberal globalists and Europeanists who dominate the “establishment.”

Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump welcomes pro-Brexit British politician Nigel Farage at a campaign rally in Jackson, Mississippi, on Aug. 24, 2016. Like Brexit, Trump’s victory over Hillary Clinton in the U.S. presidential election was driven by voters turning against the political establishment. (AP Photo/Gerald Herbert)

President Barack Obama, Trump’s predecessor, had made a point of his anationalism. For a time, by way of illustration, he refused to wear the traditional flag lapel pin worn by politicians in office. He regularly renounced any claim that the United States exhibited national “exceptionalism.” He advised Americans that they should accustom themselves to a more modest, and undistinguished, national economic productive rate of less than 2% per annum. He materially reduced defense spending so that the United States would no longer loom large as a military power. He increased welfare provisions as evidence of national vulnerabilities. Whatever his ultimate intentions might have been, it seemed clear that he wished to dampen national sentiment. Trump’s call to “Make America Great Again” was seen as antithetical, and offensive, to all of that.

In the Western industrialized states nationalism has been largely in disfavor since the conclusion of the Second World War. The reasons are many and varied and need not detain us. What we are obliged to do is understand something of how a damping of national sentiment is undertaken and propagated.

One need only attend the lecture halls of American institutions of advanced learning to come away with an awareness of what is transpiring. The atmosphere there is thick with pervasive anationalism. Lecturers in social science, liberal arts, and law will opine in excruciating detail about the history of “ethnic cleansing” of North America undertaken by “invading hordes of White settlers.” They will be eloquent in the account of the horrors that attended the enslavement of Blacks—and the exploitation of immigrant labor to satisfy the rapacity of “Big Business.” That is generally coupled with detailed renderings of abuses suffered by homosexuals, lesbians, bisexuals, and transgender individuals—anyone who does not conform to traditional norms.

These sentiments are reinforced in the entertainment media and repeated in many of our churches. Failure to accept the message without resistance exposes one to charges of “racism” and “homophobia.” Among the results one finds a measureable change in attitude toward national symbols in the general population—and on university campuses many students will more readily fly the flag of some Third World country than that of their own nation. Those who resist are cast into the bushel of “deplorables.” They are those who irrationally “cling to their Bibles and guns.”

Presidential candidate Donald Trump addresses supporters at a rally in Akron, Ohio, on August 22, 2016. (Angelo Merendino/Getty Images)

Trump took issue with all of that. He has sought to reanimate the United States with a soft, or sentimental (if well-armed) nationalism. His populism depicts the nation as an admirable cultural and historic continuity—neither biological nor class-based. It finds its strength not in a particular ideology, but in traditional symbols—in its history, its flag and its national anthem. His is a relatively benign form of nationalism. He is not a statist. His nationalism is neither aggressive nor expansionist. He will use, or invoke, the threat of violence whenever he is convinced (at times perhaps incorrectly) that the security, territory, or citizens of the nation are in jeopardy. Unlike other nationalisms, that of Trump’s United States has no specific racial reference; it has no irredentist claims on the territory of others, nor does it seek to secure external “vital spaces” to supply it resources.

All that makes the media response to his self-identification as a “nationalist” decidedly curious. Trump speaks to the sentiments of common people of the United States—and every survey of that population shows it overwhelmingly prideful of the nation and respectful of its symbols. He speaks to that sentiment when he commits himself to making the nation “great again,” to have it respected and admired. That is why he seeks a restoration of its industrial base—by making a direct appeal to the immediate material interests of workers—promising increments in pay and benefits, together with comprehensive tax cuts. His intention to reindustrialize the nation through the reduction of regulatory constraints and tax cuts favoring business has a following among entrepreneurs—and his plan to construct a wall along the nation’s southern border to ensure the territorial integrity of the nation against uncontrolled immigration has engaged the support of those who fear the impairment of sovereignty as well as a dilution of traditional culture. Increases in defense spending are seen as contributions to the defense of both national security and sovereignty. All of this is inspired by nationalism.

Such policies constitute the core of Trump’s populism—and resulted in an electoral coalition that won him the presidency. Whatever data we have (and it is fragmentary and uncertain at best) indicates that his coalition is composed, in substantial part, of voters characterized by a relatively low level of advanced (post-secondary school) education, relatively low annual income, and relatively little in personal savings. As such, many of those attracted by Trump have probably avoided much of the liberal indoctrination irresistible at university, and actively welcome the reindustrialization of the nation and attendant benefits. They are relatively insecure and many are concerned that an unrestricted flow of immigration might jeopardize their employment opportunities and standard-of-living circumstances.

Beyond that relatively stable core, the electoral coalition contains important segments of potential instability. With the improving economic circumstances, and consequent full employment, business interests—both agricultural and industrial—may find Trump’s attempted populist control of immigration unserviceable. They might prefer the flow of low wage, unskilled labor that unrestricted immigration delivers.

There is suggestive evidence that such a concern may have already matured. Although his Republicans have a legislative majority in the national congress, Trump has been unable to secure the funds to construct his border wall. Members of his own party have shown reluctance to provide the requisite monies. Many Republicans in congress represent business constituencies, and their evident reluctance to fund Trump’s border wall may reflect those interests.

As workers find employment in the reindustrializing economy, and as their life circumstances become more secure, their interests may well turn elsewhere. Their nationalism is open textured. It then becomes unclear what their future political dispositions may be. One can hardly have confidence that their enthusiasm for Trump’s populism will continue unabated. Some polls suggest that the support for the policies that won Trump the presidency may already be dissipating. Opposed to all that we have the unwavering opposition to his populism by well-entrenched progressives and liberals.

Surrounded by applauding steel and aluminum workers, President Trump holds up the ‘Section 232 Proclamations’ on steel imports that he signed at the White House on March 8, 2018. (Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

Trump’s election to the presidency of the nation precipitated an unprecedented hysteria among establishment globalists and anationalists. The entirety of the communications, educational, and entertainment media has been, and resolutely remain, opposed to everything he proposes. Liberal control of the universities ensures the continued production of anti-Trump professors, journalists, lawyers, essayists and entertainers—so that when his support base diminishes in any measure, and for whatever reason, there are anti-Trump replacements ready to fill the vacancies.

Under any circumstances, Trump can only be president for a maximum of eight years. The Constitution of the United States prohibits any more than that. Once out of office, a successor can undo virtually everything accomplished. Little other than his appointments to the Supreme Court can have enduring effect. Given the nature of his populism, it can only be largely transient.

Uninhibited by reality, Trump’s opponents have chosen to attack the legitimacy of his presidency by charging him with “racism,” “homophobia,” “misogyny,” and the “promotion of violence.” Perhaps the most outrageous charge against Trump’s populism is that it is “fascist.” No other word in the lexicon of contemporary politics evokes so emphatic a repugnance. It conjures up images of racial oppression and genocide, against a background of absolute dictatorship and unrelieved oppression.

However popular the notion may be in some circles, none of this applies to the populism of Trump. Unless one chooses to speak at a level of abstraction at which virtually anything can be said, there is no fascism in Trump’s populism.

Those who advance the claim often argue that Trump’s populism is nationalistic—so was the populism of Benito Mussolini. But then, virtually every modern populism has been, or is, nationalistic. The cry of the Marxist fidelistas of Cuba is “the fatherland or death.” There has never been a question of the nationalism of Mao Zedong. Even Josef Stalin, the Marxist internationalist, had to ultimately seek to instill “patriotism” in his populism—and there is no question about the nationalism of Vladimir Putin’s populism. A sense of national pride certainly does not make Trump’s populism fascist.

Then, there is the question of charisma. Mussolini was charismatic—so is Trump. However the term is defined, it is agreed that both Trump and Mussolini can be so characterized—as can almost every other populist leader. The history of populist politics, in fact, is littered with charismatic figures.

Once one moves below the level of such abstractions, one recognizes the vastness that separates the populism of Trump from that of historic fascism. In the first place, Trump’s populism plays out in a viable representative democracy. At best, he can serve a total of eight years. The situation for fascism was fundamentally different.

First of all, historic fascism arose through violence. The representative system into which it injected itself was fragile. Organized socialism, some elements of which aped Lenin’s Bolshevism, had seized major factories in the industrial regions of the peninsula. Municipalities had been taken by armed “Red Guards”—returning veterans had been assaulted. The response to all of this by the government was tepid. Citizens feared not only the loss of their property, but their lives as well. The result was a massive, if inarticulate, resistance on the part of the general population.

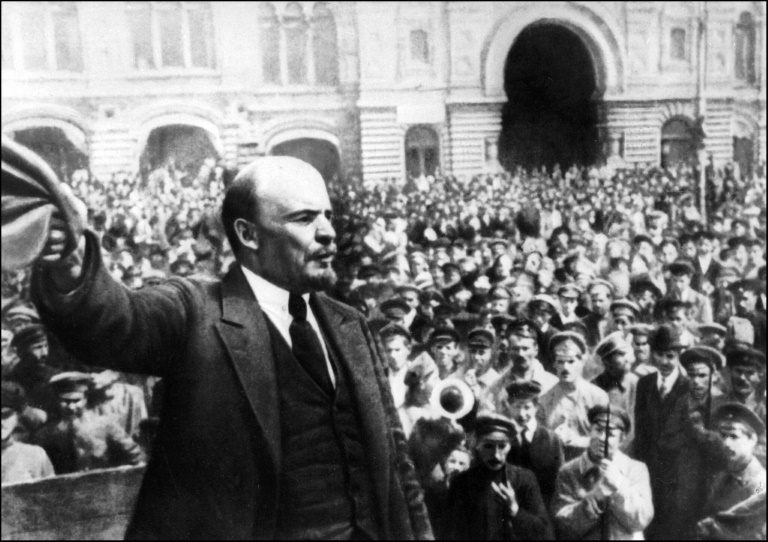

V. I. Lenin addresses a meeting in Moscow in 1919. (AFP/Getty Images)

In 1919, Mussolini founded a movement predicated on a response to what he and his followers understood to be a betrayal of a military victory purchased at staggering cost. Even before the end of the Great War, Mussolini had spoken of the “aristocracy of the trenches” as his intended recruitment base. He sought to mass mobilize the hundreds of thousands of combat veterans to mount an armed resistance to organized, anti-nationalist, and anti-military, socialism—as well as the liberal government that supplied it its environment.

His call resonated not only among combat veterans, but among property holders and nationalists as well. In the course of fascism’s mobilization, it received collateral support from the national security forces that had been vilified by organized socialism. We have convincing evidence that the security forces assisted fascist squads in their armed suppression of organized socialism. Being combat trained, the fascist squads quickly defeated their opposition—dismantling their communications and command structure. By 1922, there was no force on the peninsula that could resist fascism. The king called upon Mussolini to form a government. Populist fascism had come to Italy.

Italian fascist dictator Benito Mussolini delivering a speech. (Fox Photos/Getty Images)

One need only compare the history of fascism with that of Trump’s populism to recognize the irreducible differences that distinguish them. Mussolini’s succession to power did not depend on the occasional votes of a transient constituency. Fascism did not seek the support of a population temporarily aggrieved by the political system. From its very founding in 1919, fascism was animated by convictions concerning the mass mobilization of a durable support base. Mussolini had early settled on combat veterans as his primary recruitment demographic. The fascist literature from the period survives and testifies to the fact.

The grievances of veterans were enduring—and veterans were available in sufficient number to secure victory in popular elections. In defense of their fatherland, they had sacrificed everything. They had witnessed their comrades die in the service of a nation renewed. Fascist strategists recognized that the program to which fascism had committed itself by the time of its founding—the economic and industrial development of the economically retrograde peninsula—required protracted political control, social stability and comprehensive commitment. That demanded an enduring and inflexible platform of support. Fascists saw that support in the multitudinous combat veterans returning from the Great War. After the victory in the streets, the veteran combat squads who fought for the revolution were organized into a militia that became the armed guard of the Fascist National Party.

The populism sought by fascism was the arduous populism of developmental nationalism. They did not expect its instauration to be the consequence of an election. Given the presence of an established socialist opposition, they understood that violence would be essential to their success. Populisms predicated on developmental nationalism frequently acknowledge the role of violence in their establishment and success. The history of developmental populism in the Soviet Union, China, Cambodia, Vietnam, and Cuba, is sufficient to establish that.

Providing the foundation for economic growth and industrialization—constructing a suitable communications, transportation, and energy distribution network, as well as collecting the necessary human and financial capital for development in austere circumstances—requires an entirely different set of policies compared to a program of reindustrializing an established system. Marshalling continued support for an entire program of national economic growth and industrial development would require the studied orchestration, or imposition, of compliance behavior. Within four years of coming to power, fascism dismantled the representative democracy of Savoyard Italy to introduce what would be an enduring single-party dictatorship.

For fascism, this was undertaken by inculcating the population with a set of public beliefs that took on the imperative qualities of a political religion. It was instilled where necessary by fear of potential punishment, and reinforced by the collective sentiment born of the wearing of uniforms and the sharing of symbols, together with the regular performance of ritual. Similar programmatic phenomena are recorded in many of the developmental populisms of the twentieth century. It has been seen in the Soviet Union of Josef Stalin, in Mao’s China, and in Pol Pot’s Kampuchea. There is none of that in Trump’s populism—and it would be ineffectual if attempted.

The distinction here is the distinction between the populism that arises in less developed, marginalized economic communities and those populisms that arise in industrialized (and essentially democratic) nations. The one involves enduring programs of mass mobilization, sacrificial labor, dedication, and obedience—that often consume the lives of millions of innocents. The other involves winning episodic elections. Fascism is the paradigmatic instance of the first, Trump’s populism is an incarnation of the second.

One need only read the fascist doctrinal literature of the period to recognize the source of the difference. Fascists aspired to totalitarian control of their demanding developmental environment for an anticipated period measured in decades. Trump’s populism seeks to win the next election. Its time horizon is measured in months. Almost all its tangible effects will be transitory and almost entirely remediable by its successor. That anyone should find an instructive similarity between the two systems could only count as evidence of prejudgment.

As long as populism arises in industrialized, viable, representative democracies its overall effects are largely transitory. The populism in advanced industrial environments arises largely in reaction to the excesses of abundance. In the United States public immorality and the abandonment of decency is accompanied by the annual death of more Americans through street violence than the loss of American lives on the battlefields of the Middle East. Each year, together with the death of thousands of citizens through anarchic violence, hundreds of thousands of unborn infants perish through their voluntary abortion by their parents.

Liberalism’s narcissism and advocacy of individual self-indulgence, its anomic and amoral life style, its irreligiosity, and consequent anti-traditionalism—all consequences of abundance—together contribute to consequences that prompt political dissatisfaction among the more mature segments of the population. Such an environment precipitates the appearance of a charismatic to rally those politically disaffected and effectively disenfranchised. The result is the appearance of a “conservative” populist nationalism. Such reactions generally have some initial success, but they are predictably not enduring. Unless they can fundamentally alter the system, through some political alchemy, they will largely disappear with new elections.

There are communities of yet uncertain populism. Putin’s Russia and Erdogan’s Turkey are among them. They give evidence of a populist nationalism as yet not fully articulated. The properties of such systems vary as circumstances change. Their future remains obscure. Putin’s Russia seems scheduled to run a course of an anomalous developmental nationalism.

Chinese soldiers ride in an armored vehicle while passing in front of Tiananmen Square and the Forbidden City during a military parade on September 3, 2015 in Beijing, China. (Kevin Frayer/Getty Images)

The differences between the populisms here considered are manifest. Those that appear in established and viable representative democracies are far different from those—like Putin’s Russia—that manifest themselves in industrialized but essentially nondemocratic environments. Many of the non-socialist populisms that surface in economies only marginally developed are distinctive. The populism that arose in Taiwan, South Korea, Hong Kong, and Singapore have been distinctive. Their developmental nationalism has been characteristically protracted, authoritarian, and essentially supportive of traditional values. Their populations are industrious, frugal, obedient, demonstrably moral, and overtly nationalist. Generally animated by a set of relatively formal convictions that render them compliant, they often provide the platform for what becomes a time conditioned, essentially one-party governance.

The variants of socialist developmental populism (and Mussolini’s Fascism was one such variant) constitute a distinctive subset. Some of the consequences of the populism of a socialist oriented, developmental nationalism can be observed in the behaviors of the People’s Republic of China. After a century, China is nearing the end of its developmental cycle. Its one-party state and its political religion remain fully intact. It has its charismatic life-time president.

Within the next two dozen years China may well surpass the productive capacity of the United States. Its armed forces are growing with impressive rapidity. It poses a threat to United States dominance in the West Pacific and to the freedom of navigation through the choke points in the South China Sea. Its irredentist shadow falls across Japan, Taiwan, and the nations of Southeast Asia. In effect, like fascism, China is a classic instance of a “socialist,” nationalist developmental populism. The Chinese regularly remind us of the time when China was the Central Kingdom—the critical center of civilization. All of that suggests that rather than the imagined fascism of Trump’s populism—it is the populism of China that should occupy our serious attention.

Professor A. James Gregor is professor emeritus of political science at the University of California, Berkeley. He is the author of thirty academic volumes and is a Knight of the Order of Merit of the Republic of Italy.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.