One hundred years ago this week, the first rays of dawn were poking through the trees near the US military cemetery in Thiaucourt, France, as Lieutenant Arthur E. Dewey knelt in the muddy earth beside one of the hundreds of crosses in the field.

Like the thousands of others dotting the landscape, this white marker designated the final resting place of one of the Americans who had fallen in the battle of St. Mihiel.

Bundled against the morning chill, Dewey and an assistant began their grisly task — painstakingly sorting through badly decomposed remains, searching for dog tags, photographs, scraps of paper, or anything else that could possibly identify the body. Nearby sat a gleaming steel-gray Springfield casket, its polished surface contrasting sharply with the gritty russet soil of the grave site.

Finding nothing on the body or its tattered clothing, they respectfully placed the remains on a blanket they had brought for the purpose. Then they wrapped the fallen soldier and placed him into the waiting casket.

At exactly the same moment, an identical scene was playing out in three other American cemeteries in France: Belleau Wood, Bony, and Romagne-sous-Mountfaucon. Each served as the final resting place for thousands of unidentified American soldiers who had fallen in one of the United States’ major engagements in World War I.

One of those bodies would become the Unknown Soldier interred in in Arlington National Cemetery.

I retell the story of that selection process in my new bestselling book, The Unknowns: The Untold Story of America’s Unknown Soldier and WWI’s Most Decorated Heroes Who Brought Him Home. The Unknowns follows eight American heroes who accomplished extraordinary feats in some of the war’s most important battles. As a result of their bravery, these eight men were selected to serve as Body Bearers at the ceremony where the Unknown Soldier was laid to rest at Arlington Cemetery.

The plan to honor an Unknown Soldier got off to a rocky start. Several other nations had already constructed monuments to recognize the sacrifices of their unidentified fallen, but U.S. Army Chief of Staff General Peyton C. March initially thought it was a terrible idea and dismissed it out of hand. He held on to the hope that the Graves Registration Service (GRS) would eventually be able to identify all the bodies buried in Europe.

However, as the Americans saw news coverage of other nations’ Unknown Soldier ceremonies, the public began to clamor for a monument of their own. Marie M. Meloney, the editor of a popular women’s magazine, trumpeted the idea, writing to March, “There is in this thing, the way England has done it, the essence of democracy, and the soul of a people. It is the kind of thing which should have found birth in America. I want you to do the fine, big human thing that no one else in America has initiated. . . . It brings patriotism home to men in a personal way.”

Newspapers and Republican New York Representative Hamilton Fish, a hero and officer in the “Harlem Hellfighters” during the war, also got behind the idea. General John Pershing, who had led the American Expeditionary Forces, added his support, and the political pressure proved too much for lawmakers to resist. On February 4, 1921, Congress approved Public Resolution 67, which called for the construction of a simple tomb for an unknown soldier at Arlington. American would honor its Unknown Soldier with an official ceremony to be held on Armistice Day, November 11, 1921.

The next nine months required a flurry of activity to prepare for the big day. The GRS devised complicated plans to ensure that the body to be buried would remain anonymous, designers drew up plans for the memorial, and excavators began preparing the site. General Pershing also played a role, choosing the heroes who would serve as body bearers for the Unknown Soldier — each enlisted man was also chosen to tell a part of the AEF’s story in Europe.

One body selected from each of the four American military cemeteries throughout France arrived at the city hall in Châlons at precisely 2:50 p.m. on Sunday, October 23, 1921. There they lay in state as crowds of grateful French citizens paid their respects, many of them adding bouquets to the heaps of flowers piled around the caskets. “Each person in that long, steady line, as he reached the door, bowed the head, offering a silent prayer, a prayer of sorrow and of thanksgiving, for the eternal rest of the souls of those Unknowns, far from home, who had given their lives in assisting France,” Dewey recalled. “Hardly a dry eye was to be seen in the crowd, for nearly every French family had lost dear ones during the awful four years of the war.”

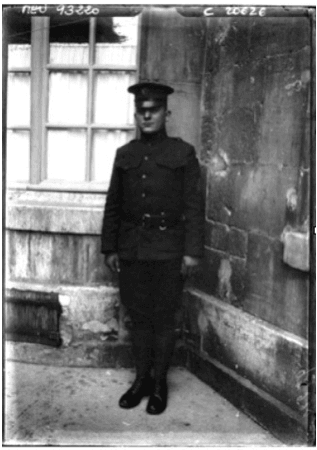

That night, the caskets and bodies were secretly shuffled to ensure that no one would know which cemetery the Unknown Soldier had come from. And the next morning, Sergeant Edward Younger received word that he would have the honor of selecting the Unknown Soldier. A quintessential doughboy, a citizen-soldier from Chicago, Younger had battled and bled for his country, receiving two wound chevrons to recognize his injuries in battle. “I had gone over the top many times, had known the agony of waiting for the charge,” Younger later recalled. “But nothing had paralyzed me as that simple announcement did.”

Edward Younger, the man who selected the Unknown Soldier. Bibliothèque Nationale de France

With 50 French and American officials looking on, Younger circled the caskets in the city hall several times, carrying a clutch of white roses. “I was numb. I couldn’t choose,” he recalled. “Then something drew me to the coffin second to my right on entering. I couldn’t take another step. It seemed as if God raised my hand and guided me as I placed the roses on that casket. This, then, was to be America’s Unknown Soldier, and by that simple act I had started him on his road to destiny.”

The ceremony to select the Unknown Soldier was only the first of many official events to honor the fallen American before he reached his final resting place in Arlington. The body lay in state in the Châlons city hall until 5:00 p.m., and a steady stream of French mourners passed by. Then a French honor guard lined up, and officers on horseback led a procession as the casket was transported by horse-drawn caisson to the train station. There, the body again lay in state before heading to Paris and then to the port city of Le Havre.

In Le Havre, the French citizens again massed for a ceremony to honor the American Unknown Soldier. A processional wound through town from the train station to the dock where the USS Olympia was berthed. Beside the ship, French and American officials expressed their thanks for the sacrifice that America’s doughboys had made in the war, and a band played “La Marseillaise” and then “The Star-Spangled Banner” as the casket was carried aboard the Olympia. As the ship left the harbor, the music shifted to Chopin’s Funeral March, and French vessels fired in respect before accompanying the American ship to sea.

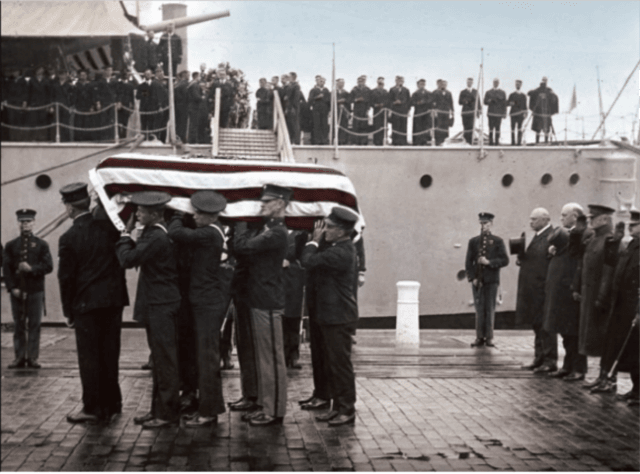

The Olympia arrived back home in Washington, D.C., on Wednesday, November 9, a drizzly, foggy day. A regiment of cavalry and a mounted band waited solemnly in the wet weather before accompanying the Unknown Soldier to the U.S. Capitol and ultimately to Arlington.

Patrick K. O’Donnell is a bestselling, critically acclaimed military historian and an expert on elite units. He is the author of eleven books. The Unknowns is his newest and is featured at Barnes and Noble stores. O’Donnell served as a combat historian in a Marine rifle platoon during the Battle of Fallujah and speaks often on espionage, special operations, and counterinsurgency. He has provided historical consulting for DreamWorks’ award-winning miniseries Band of Brothers and for documentaries produced by the BBC, the History Channel, and Discovery. PatrickkODonnell.com @combathistorian

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.