San Francisco International Airport officials ask the public to submit photographs for the next two months for consideration for permanent display in the Harvey B. Milk Terminal. The San Francisco Board of Supervisors, the same governing body on which Milk and his assassin once sat, voted to name Terminal 1 in honor of the gay-rights activist earlier this year.

“The images will be reproduced at approximately 14”x 20” and interspersed with informational text,” the call for photographs informs. “Each selected contributor will receive an honorarium in the amount of $500 per image selected for Exhibition Phase 2 and will be credited in the exhibition space.”

One photograph not likely to find itself included in the exhibit shows Harvey Milk speaking passionately in support of Jim Jones while inside a raucous rally at Peoples Temple in the summer of 1977. When a New West magazine exposé charged Peoples Temple with financially exploiting members, staging fake faith healings, and even ordering the beating of a teenage lesbian for hugging a woman, many politicians ran from Jim Jones. Harvey Milk rushed to his defense. As he had earlier written Jones, “The first time I heard you you made a statement[:] ‘Take one of us and you must take all of us.’ Please add my name.”

Milk, good to his word, remained loyal. But even as interest in his life has exploded along with the success of the gay-rights movement that he once served, this puzzling alliance remains off limits. From the Academy Award-winning Harvey Fierstein-narrated Times of Harvey Milk documentary, which mentions the Jonestown tragedy in passing without noting the supervisor’s alliance with Jones, to the Oscar-winning biopic Milk starring Sean Penn, chroniclers of Milk’s life delicately avoid the subject of Harvey Milk’s relationship with Jim Jones.

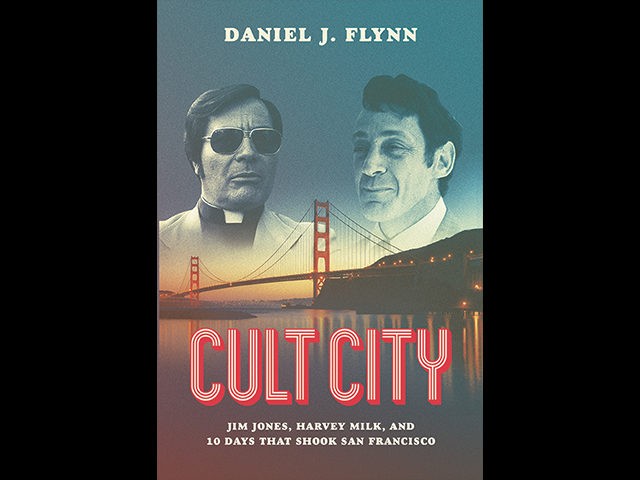

In researching Cult City: Jim Jones, Harvey Milk, and 10 Days That Shook San Francisco, I discovered that research institutions overflow with correspondence from Harvey Milk to Jim Jones and to powerful leaders in praise of Jim Jones. Although many San Francisco pols associated with Jones to one degree or another, Milk, along with future San Francisco mayor Willie Brown and local power-broker Carlton Goodlett, acted most zealously and uncritically in promoting the Peoples Temple leader.

“Such greatness I have found at Jim Jones’ Peoples’ Temple,” Milk gushed in a letter to Guyanese Prime Minister Forbes Burnham. To Jimmy Carter, the president of the United States, Milk wrote: “Rev. Jones is widely known in the minority communities here and elsewhere as a man of the highest character, who has undertaken constructive remedies for social problems which have been amazing in their scope and effectiveness.” To Joseph Califano, the secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare, he remarkably described Peoples Temple as “the first to defend the constitutional rights of others,” Jonestown as “a beautiful retirement community in Guyana,” and the group, which imported food into its agricultural project until the end, as “alleviating the world food crisis.”

Though Milk issued effusive praise for Jones and Jones spoke of Milk as “one of our deepest supporters,” the relationship was also transactional.

Jim Jones provided Harvey Milk a printing press, conscripted campaign “volunteers,” and free publicity. When Milk needed entertainment for a street fair he had organized, Peoples Temple provided professional-level entertainers. After one of Milk’s lovers took his own life, the Temple sent dozens of condolence letters from Guyana with the stated expectation that he might visit or even come to live in the jungle commune.

In exchange, Milk provided Jones legitimacy. When former Peoples Temple members accused the group of fraud, beatings, and other criminal activities, Milk rushed to his patron’s defense. He wrote to New West objecting to the magazine’s investigation. In his letter to Jimmy Carter, whose wife knew Jones personally, Milk pleaded with the president to not intervene in an intercontinental custody battle that pitted a boy’s parents against Jones, his kidnapper. Carter’s State Department took Jones’s side, and the boy, John Victor Stoen, died in Jonestown without ever seeing his parents again.

The last place in the United States where so many of the poisoned Peoples Temple members stepped foot was San Francisco International Airport. It was here where Tim Stoen plaintively petitioned Jim Jones to deliver his son, instructing him to inform him of “the exact time and flight of John Victor’s arrival at San Francisco International Airport.” But six-year-old John Victor Stoen never arrived at San Francisco International Airport.

Forty years after his death, the man who judged Stoen’s father as guilty of “bold-faced lies” and portrayed his mother as engaging in “blackmail” posthumously graces an SFO terminal with his name. The pictures that soon accompany it will undoubtedly tell only part of the story.

Daniel J. Flynn is the author of Cult City: Jim Jones, Harvey Milk, and 10 Days That Shook San Francisco (ISI Books, 2018).

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.