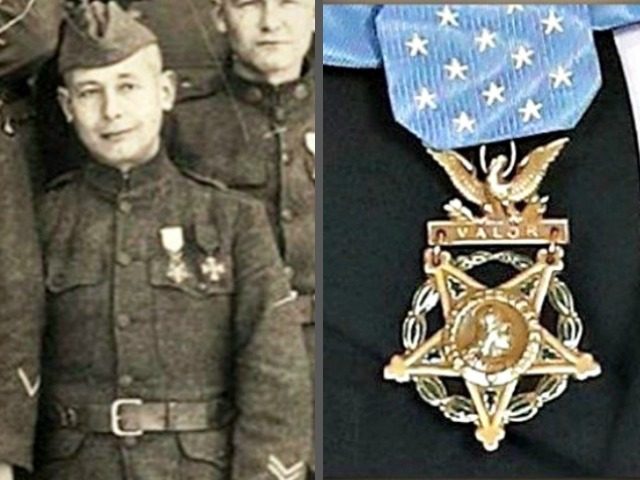

With his boyish face and small stature, New York Private Frank J. Bart did not look much like a hero. On October 3, 1918, Bart’s unit, Company C of the 9th Infantry Regiment, found itself pinned down in front of a pair of German machine guns. Not only were the Americans unable to advance on their objective — German fortifications on Blanc Mont Ridge — the German gunners were hitting their targets. Bart’s comrades were dropping on all sides.

With telephone communication in its infancy, Bart served as a runner, a messenger who would carry information from one unit to another. He was quick on his feet and accustomed to danger as the runners often had to leave the relative safety of the trenches and dash across to fortifications manned by other units. This was one of the most perilous positions of any army on the Western Front.

That experience served him well on Blanc Mont Ridge. Instead of freezing in the onslaught of fire, Bart grabbed a Chauchat machine gun. Although the weapons were renowned for their tendency to jam, on that day the French-made Chauchat did not fail. All alone, he charged toward the first machine-gun nest and unleashed a torrent of lead on those inside.

After taking out the first nest, Bart repeated his performance with the second machine-gun emplacement, killing all the Germans inside.

Bart’s actions allowed the 9th to capture Médéah Farm on the far right of Blanc Mont Ridge. And for his courage under fire, he later received the Medal of Honor.

This month marks the 100th anniversary of Bart’s heroics on Blanc Mont Ridge. While few people today remember that fateful assault, it was one of the bloodiest battles for the U.S. 2nd Division. Its capture has been rightfully called the “single greatest achievement of the 1918 campaign.”

I tell the story of that epic battle in my newest bestselling book, The Unknowns: The Untold Story of America’ Unknown Soldier and WWI’s Most Decorated Heroes Who Brought Him Home. Released in May, The Unknowns follows eight American heroes who accomplished extraordinary feats in some of the war’s most important battles. As a result of their bravery, these eight men were selected to serve as Body Bearers when the Unknown Soldier was laid to rest at Arlington National Cemetery.

Several of those Body Bearers, including the man who selected America’s Unknown Soldier, fought at Blanc Mont. The French Army had been attempting to take the high point for years. The only result was tens of thousands of men gored on the seemingly impenetrable defenses.

The Germans had converted the white limestone ridge into a fortress. Row upon row of machine-gun emplacements, pillboxes, and barbed wire made the ascent all but impossible; the Germans had nearly 400 machine guns and dozens of artillery pieces dug in to the side of the mountain. They had carefully positioned their concrete redoubts, enabling them to triangulate their fire, and scores of concrete pillboxes dotted the area, their deadly fire supporting the main redoubts. In addition, a system of honeycombed trenches and tunnels connected the strongpoints, enabling the Germans to reinforce them or recapture overrun positions. Blanc Mont was crucial to the German defenses in the Rheims sector of the Western Front. The Germans intended to hold the ridge at all costs.

The ground in front of Blanc Mont bore testimony to the Allies’ inability to take the stronghold in the preceding four years of war. Husks of trees, bleached bones, broken equipment, and scores of lonely helmets with bullet holes drilled through their rusted metal skins dotted the lunar-like landscape. Numerous allied forlorn assaults had only produced thousands of casualties.

Now, it was up to Bart’s 2nd Division, which included the 3rd Brigade (9th and 23rd Army Infantry Regiments) and 4th Brigade (5th and 6th Marines), to capture the German fortification.

They went over the top at 5:50 a.m. the 3rd of October. “For a moment, the sun shone through the murk, near the horizon—a smoldering red sun, banded like Saturn, and all the bayonets gleamed like blood. Then the cloud closed again.” In front of them lay the result of the previous doomed French attack on the German trenches: scores of dead soldiers formed “a wedge, thinning toward the point as they had been decimated, and at that point was a great bearded Frenchman, his body all a mass of bloody rags, who lay with his eyes fiercely open to the enemy and his outthrust bayonet almost in the emplacement.”

American heavy artillery pelted the German lines with crimson and green flames. A powerful rolling barrage rained down on the defense, creeping ahead of the advancing infantry.

The enemy responded in kind. One of the Americans recalled, “The German artillery was raising the devil with us; one shell killed eighteen horses that were being fed in a ravine about a hundred yards back of us. Our position was continually under fire.”

Countless acts of heroism, like Private Bart’s, somehow allowed the Americans to ascend the hill slowly. By the evening of October 4, the 2nd’s Marines and soldiers linked up on the crest of Blanc Mont.

It would have been a moment to bask in glory, but the French Army, which was supposed to be shielding the 2nd Division’s flanks, had failed to keep up with the Americans. As a result, the men atop Blanc Mont Ridge were now exposed on three sides. The Germans surged in counterattack, attempting to crush the 2nd.

Miraculously, the men atop the ridge held it overnight despite the bullets, shells, and gas mercilessly pouring down upon them. Having brought little food or water into battle, they scavenged the bodies of the fallen, scavenging full canteens or anything to eat.

But holding the hill was not enough for the brass. Orders came down from headquarters for the 2nd to press on toward the town of Saint-Étienne. “Orders are to attack, and by God, we’ll attack,” declared Major George Hamilton, who led the 1st Battalion of the 5th Marine Regiment.

As dawn broke, a sea of doughboys clad in overcoats and army tunics with their gas-mask bags slung around their necks advanced in columns of battalions. The Germans immediately responded, opening up with machine guns and artillery, saturating the area with high explosive shells and deadly poison gas. “Singing balls and jagged bits of steel spattered on the hard ground like sheets of hail; the line writhed and staggered, steadied and went on, closing toward the center as the shells bit into it . . . red flashes, full of howling death.”

Casualties mounted, and some of the men broke. They ran for the rear until Hamilton and another officer drew their guns and forced the men to stop.

Hamilton organized the men for a charge toward another ridge near Saint-Étienne, but the Germans had circled around behind and were now firing from that direction, as well. “The fire from the ridge itself was so intense,” recalled the report. “Here we were practically surrounded and receiving a galling fire from three directions. There was nothing to do but advance on up the hill.” The men were trapped in a harrowing area they dubbed, “The Box.”

The Marines gained the ridge but had lost so many men on the way that they found themselves unable to advance any farther. Hamilton sent a message to headquarters: “Our forces are so much diminished that we do not extend over to the original left of the sector. . . . This battalion will go, or attempt to go where you order it. You should understand, though, that your regiment is now much depleted, very disorganized, and not in condition to advance as a front line regiment. . . . It is hard to say ‘can’t,’ but the Division Commander should thoroughly understand the situation and realize that this regiment can’t advance as an attacking force. Such an advance would sacrifice the regiment.”

The Americans dug in for another sleepless night of shelling. One of the 5th Marines recalled, ” Away out of the air we could hear the hissing of a shelling headed our way like a red-hot iron dipped in water. As it drew nearer, the hissing grew louder, and when it hit the ground with a crash, everything around us shook. I lay and trembled, as did the others in my foxhole, so much that I could see it when we heard a shell coming we stopped trembling, stopped breathing, closed our eyes, pulled our muscles taut enough to burst, and waited; it seemed a long time, but it was possibly only ten seconds. When the shell burst and we found we still had a connection with a thread of life, we started to breathe again, opened our eyes; perfectly normal for a few seconds, then began to tremble again.”

This was life and death, fighting in “The Box.”

After several more days of hard fighting, the 2nd Division eventually captured Blanc Mont and secured a foothold in Saint-Étienne. French Field Marshal Pétain later proclaimed, “The taking of Blanc Mont is the single greatest achievement of the 1918 campaign.”

The Americans had won the battle, but at a staggering cost. From its original strength of 1,000 men, Hamilton’s 1/5 now had only about 150 Marines. In all, the 2nd Division suffered 4,832 casualties.

And not all of those deaths had been at the hands of the enemy. One participant recalled that one of the Marines “had been caught rifling the pockets of the dead of his battalion. He was dead too, [fratricide] as a man or two could tell. There are some laws that must not be transgressed.”

Patrick K. O’Donnell is a bestselling, critically acclaimed military historian and an expert on elite units. He is the author of eleven books, most recently The Unknowns: The Untold Story of America’ Unknown Soldier and WWI’s Most Decorated Heroes Who Brought Him Home. @combathistorian

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.