This week marks the hundredth anniversary of the beginning of America’s largest and deadliest battle: The Meuse-Argonne Offensive. One of the greatest stories of World War I and that battle involved Sergeant Alvin York.

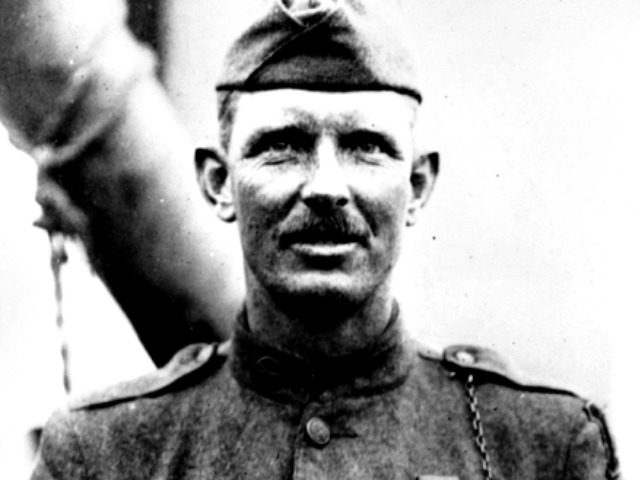

Born in the backwoods of Tennessee, York had attended school only through the third grade, but he knew plenty about farming, blacksmithing, hunting and fighting. He was also a crack shot, winning numerous local shooting competitions. In his twenties, the red-headed man with a bushy mustache gained a reputation as a hard-drinking rabble-rouser. But after seeing a close friend killed in a bar fight, York became a born-again Christian who devoted himself to his faith with all the fervor he had previously given to boozing and brawling.

When he was drafted, York first claimed conscientious objector status due to his religious beliefs. But after careful consideration, he changed his mind and entered the 82nd Division of the U.S. Army as a private.

Like the rest of the 82nd, York saw his first real action at the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. Fresh off the success of the battle of St. Mihiel, where the 82nd was held in reserve, the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) launched an assault on Germany’s famed Hindenburg Line. Their goal: to breach the most heavily defended real estate on the entire Western Front and ultimately to capture the railway hub at Sedan, severing German supply lines.

Over the course of three years, the Germans had converted the Argonne Forest into a fortress. A strip of rocky, mountainous woods about six miles long, the terrain provided defensive cover and murderous, natural kill zones. The Americans faced mountains of barbed wire, a maze of interlocking trenches, and concrete pillboxes designed to lure incoming attackers into dead ends where German heavy artillery and field guns were poised to rain down showers of death. Machine guns, manned by expert German gunners, were set in concrete bunkers and redoubts and had interlocking fields of fire aimed at goring attackers with enfilading (flanking) fire.

American officers compared the ground to that of the Battle of the Wilderness in the Civil War, notable for its heavy underbrush and equally heavy casualties. One described the Argonne as a “natural fortress . . . beside which the Wilderness in which Grant fought Lee was a park.” Another described the Meuse-Argonne as “the most comprehensive system of leisurely prepared field defense known to history.”

The long and bloody battle in the Meuse-Argonne dragged on for 47 days. Picture the opening scene of Saving Private Ryan duplicated nearly every day for nearly seven weeks. Infantry assaulted heavily defended kill boxes as deadly artillery rained down upon them and accurate machine-gun fire pierced their bodies and poison gas filled the air.

I retell York’s story and recount the Battle of the Meuse-Argonne in my new bestselling book, The Unknowns: The Untold Story of America’s Unknown Soldier and WWI’s Most Decorated Heroes Who Brought Him Home.

In a legendary episode from the battle, two battalions of the 308th Infantry Regiment, including one led by Major Charles Whittlesey, attack a key road in the Argonne Forest. When a flanking action went wrong, the 554 men found themselves far out ahead of the American lines and surrounded on three sides by the Germans. With their strength already greatly depleted, Whittlesey ordered the men to dig in.

The enemy attacked relentlessly. Whittlesey attempted to break out several times but failed. He then sent carrier pigeons requesting new orders or reinforcements. Meanwhile, the German machine-gun and artillery fire continued unceasingly, but Whittlesey’s men held.

When their efforts to overrun the small band of Americans proved unsuccessful, the Germans sent back an American prisoner with a note recommending that his comrades surrender. One of the officers recalled, “There was a good smile all around among the crowd of us, because we knew that the Germans felt that they could not take us. . . . They had tried to wipe us out every day and had been trying to wipe us out every day since we had been in the position and then had written us a note stating that they would like to have us surrender in the name of humanity.”

The Americans did not surrender.

To relieve the Lost Battalion, as it would later become known, the AEF sent in elements of Alvin York’s 82nd Division, as well as other units. Their objective was to take out more than thirty machine-gun nests on a nearby ridge and sever a German rail line supporting the front line, hopefully to relieve the German pressure on Whittlesey.

Facing the sustained fire that had pummeled the Lost Battalion for days, York’s unit saw its ranks quickly decimated by German fire. “It ’most seemed as though it was coming from everywhere,” York later recalled in his Tennessee drawl. “I’m telling you they were shooting straight, and our boys jes done went down like the long grass before the mowing machine at home. Our attacks jes faded out.”

With all of the officers in the group dead or wounded, York, then a corporal, took command as the senior noncom on the scene. Relying on his well-honed hunting skills, York told the men to circle around through the brush and approach the German high ground from the left flank. From this better vantage point, York put his shooting skills to work, picking off machine gunners as they raised their heads before firing. “Every time a head come up, I done knocked it down,” he later said.

York’s sharpshooting didn’t go unnoticed long. Determined to stop the American, a German officer and five men charged headlong toward the Tennessean. Unfazed, York razed his pistol and shot the last man in line first, then the second to the last, and so on. This approach meant the men at the front kept running without realizing their friends had fallen. It was “the same way we shoot wild turkeys at home,” York explained.

In the end, only the officer made it to York’s position. The American pointed his .45 at the German’s head and told him to have his men cease fire. “He knowed I meaned it,” York said.

The German blew a whistle, and all up and down the line, the enemy soldiers stopped firing.

Having killed 28 men, York took the rest of the Germans in the unit prisoner. He marched the lot of them back to the American trenches, where he reported to Brigadier General Julian R. Lindsey.

“Well, York, I hear you have captured the whole damned German Army!” Lindsey quipped.

“I only had 132 men,” York humbly recalled.

Patrick K. O’Donnell is a bestselling, critically acclaimed military historian and an expert on elite units. He is the author of eleven books. The Unknowns is his newest, released in May. O’Donnell served as a combat historian in a Marine rifle platoon during the Battle of Fallujah and speaks often on espionage, special operations, and counterinsurgency. He has provided historical consulting for DreamWorks’ award-winning miniseries Band of Brothers and for documentaries produced by the BBC, the History Channel, and Discovery. PatrickkODonnell.com @combathistorian

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.