Sen. John McCain (R-AZ) passed away Saturday, 4:28 p.m., at the age of 81 after a months-long battle with brain cancer.

McCain was born on a U.S. Navy base in Panama in 1936, the son and grandson of career Navy officers. He graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy and served as a Navy pilot in the Vietnam War.

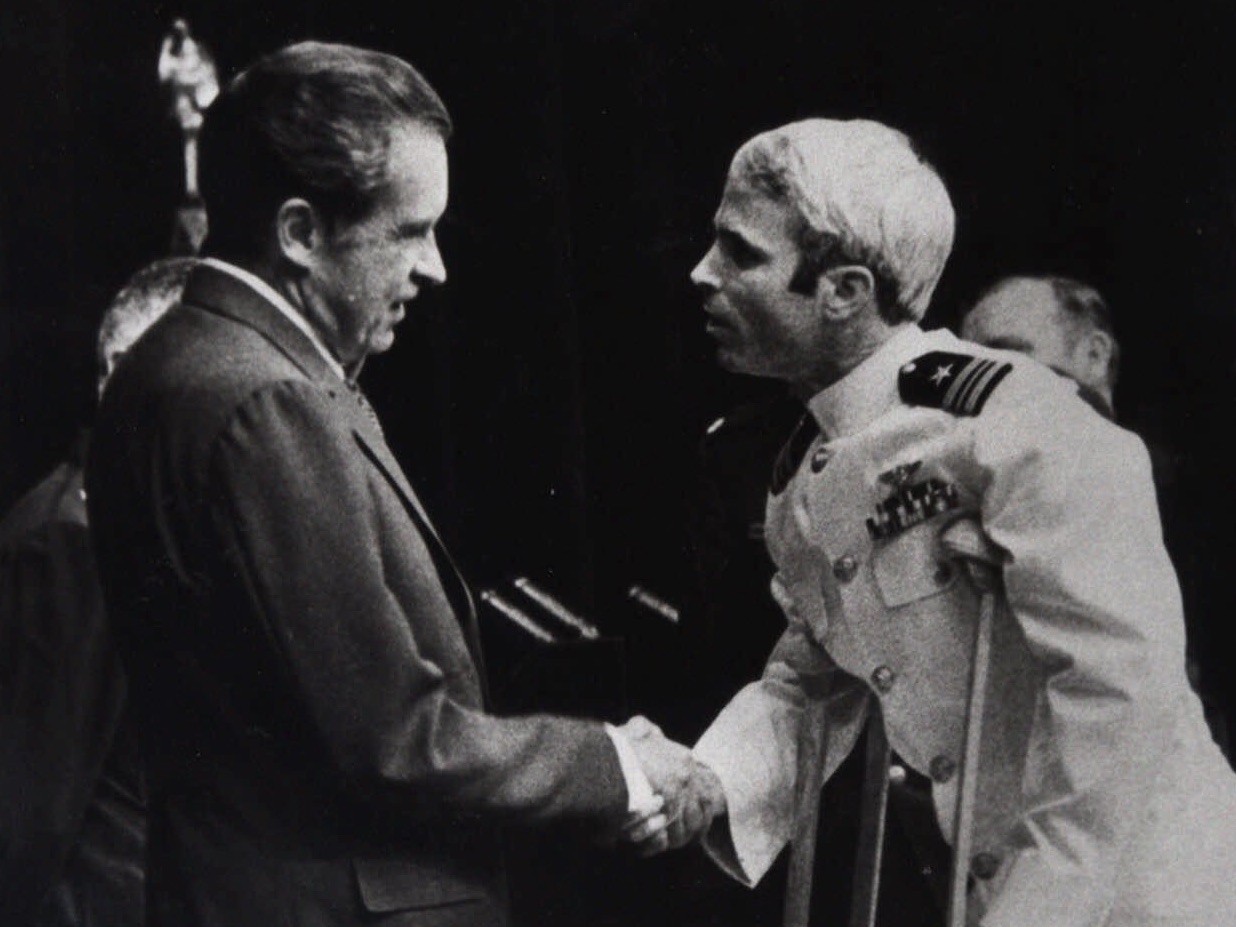

He was shot down over Hanoi in 1967 and was a prisoner of war for five and a half years. McCain was tortured by the North Vietnamese, leaving him permanently disabled. He famously refused to be released ahead of POWs who had been captured first — denying the enemy a propaganda coup, since his father was then the commander of all U.S. forces in Vietnam.

Upon his release in 1973, McCain studied at the Naval War College in Washington, DC, where he puzzled over the question of America’s struggles in Vietnam, ultimately concluding that lack of political commitment to victory had led to defeat. It was a lesson that would guide his later approach, in Congress, to America’s foreign interventions.

McCain was assigned to be the Navy’s liaison to the Senate in 1977, which served as his introduction to politics. He retired in 1981 and ran for Congress in Arizona’s first congressional district in 1982, and won. He opposed U.S. intervention in Lebanon, defying President Ronald Reagan, warning that there was no clear strategy for victory. He was proved correct, tragically, when a terrorist drove a truck bomb into the U.S. Marine barracks in Beirut later that year, killing hundreds of American and French peacekeeping troops and leading to an American withdrawal.

In 1986, McCain won his first term in the U.S. Senate. He soon found himself embroiled in scandal as one of the Keating Five, accused of intervening in a federal investigation of the Lincoln Savings and Loan, run by McCain donor Charles H. Keating, Jr. McCain was cleared of any wrongdoing beyond poor judgment, but the experience had scarred him deeply, and he committed the rest of his Senate career to fighting against corruption and waste.

McCain soon developed a reputation as a “maverick,” defying his party whenever he thought it was veering too far to the right (or, critics said, whenever it suited his own ambitions).

In 2000, McCain ran for President, mounting a strong primary campaign against Texas governor George W. Bush and winning New Hampshire, where his brand of centrist politics found traction. He lost a bitter South Carolina primary race, however, and soon ran out of steam.

In the Senate, McCain continued to build a profile as a reformer. His major achievement was the McCain-Feingold campaign finance reform law, officially known as the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act (BCRA), which passed in 2002. Many Republicans were deeply critical of BCRA, which they saw as a form of unilateral disarmament and a limit on free speech. Parts of the law were ruled unconstitutional in the controversial Citizens United case in 2010.

McCain also joined the “Gang of 14,” a bipartisan group of Senators that fought to preserve the filibuster after the Republicans threatened to end it in response to Democrats repeatedly blocking President Bush’s judicial nominees. And McCain continued to work with Democrats, notably Sen. Ted Kennedy (D-MA), in proposing immigration reform bills that were backed by the administration but ultimately collapsed due to opposition within both parties.

In 2003, McCain joined a bipartisan majority in the Senate in supporting the Iraq War. But unlike many others, who abandoned the war as a terrorist insurgency grew, McCain remained committed to victory. Drawing from his ideas on Vietnam, he argued that the U.S. needed additional troops to secure Iraqi cities, defeat local Al-Qaeda cells, and prevent new terrorists from infiltrating. As the war grew more unpopular, he was virtually alone in his position.

However, President George W. Bush agreed with him, and launched the “surge” in 2007, in defiance of the opinions of the top military brass and the Iraq Study Group, a bipartisan panel that recommended reducing U.S. commitment to the war. McCain put aside his old rivalry with Bush and became the best surrogate for the White House’s policy.

In 2007, McCain launched a second presidential campaign. He was seen as a long-shot candidate, especially after his campaign lost several key staff members in mid-2007. But his steadfast commitment to the surge helped him to stand out among the other candidates on the debate stage, and voters were moved by the force of his convictions. In addition, it was clear that the electorate was ready for change, and McCain made the case that he alone among Republicans had a record of fighting for reforms. He won New Hampshire again, and eventually the nomination.

In the general election, McCain faced then-Sen. Barack Obama (D-IL), who had just won a spectacular, if brutal, victory over then-Sen. Hillary Clinton (D-NY) in the Democratic primary. McCain made the controversial decision not to attack Obama for his deep ties to the racist Chicago preacher Jeremiah Wright — perhaps out of a sense of guilt for his own early opposition to naming a pubic holiday for Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., which he regretted.

McCain trailed Obama for most of the summer of 2008. But he bested Obama at a religious forum hosted by pastor Rick Warren, and then upended the entire race by naming Alaska Gov. Sarah Palin as his running mate, the first time a woman had been named to a Republican presidential ticket. Palin, a corruption-busting fellow “maverick,” captured the public imagination and briefly attracted the interest of women voters disappointed by Clinton’s loss.

But the McCain-Palin lead was short-lived. The media targeted Palin with hostile, even condescending, coverage. And then, in mid-September, the global financial crisis struck as Wall Street giant Lehman Brothers collapsed. Obama, who had criticized the Bush administration’s economic performance for months, seemed prescient.

McCain decided to show leadership by suspending his campaign and returning to Washington, DC, where he backed a $700 billion bailout in the form of the Troubled Assets Relief Program (TARP), which was decried by conservatives and liberals alike. Obama, too, voted for TARP, but by the time they arrived at the first presidential debate a few days later, there was no longer any real difference between the candidates. Obama went on to win the election easily.

Conventional wisdom in party establishment circles partly blamed Palin for McCain’s loss, but she helped turn out the conservative vote in areas where the moderate McCain had struggled to connect. Recently, McCain said that he regretted choosing Palin instead of Democrat-turned-independent Sen. Joe Lieberman of Connecticut, a fellow foreign policy hawk and the man who nearly became vice president on the Democratic ticket with Al Gore in 2000.

Back in the Senate, McCain remained deeply critical of Obama’s foreign policies, as the new administration backed away from the country’s previous commitments to Iraq, creating a vacuum for the Iranian regime and new terrorist groups like the so-called Islamic State.

But McCain remained a maverick, and joined the bipartisan “Gang of Eight” in proposing a new immigration reform bill — despite having run for re-election in 2010 on a promise to “build the danged fence” along the U.S.-Mexico border. The bill ultimately died due to conservative opposition in the House.

In 2015, McCain was deeply critical of Donald Trump, who had entered the race for president on a platform of strong opposition to illegal immigration. In response, Trump aimed a pointed insult at McCain’s war record: “I like people who weren’t captured.”

That ignited a feud that never ended. McCain’s decisive, dramatic “thumbs-down” vote to defeat an effort to repeal Obamacare in July 2017 was widely perceived as motivated by personal revenge.

McCain announced that he had brain cancer last July, but continued to work in the Senate as he received treatment. His condition worsened in recent months, and he returned to Arizona to convalesce at home, surrounded by friends and family. His family announced on Aug. 24 that he was ending medical treatment.

He is survived by his wife, Cindy McCain (née Hensley), his first wife, Carol Shepp McCain; seven children, many grandchildren, and his redoubtable mother, Roberta, still alive at the ripe old age of 106.

Associates of the ailing Senator made it clear in the closing days of his life that he did not want President Trump to attend his funeral.

John McCain will be remembered for many things — his heroic endurance in Vietnam, his passion for reform, his battles with his own party, and his support for the military.

But perhaps the most memorable tribute came from the conservative columnist Charles Krauthammer, who wrote after McCain’s tough loss in the 2008 election: “He will be — he should be — remembered as the most worthy presidential nominee ever to be denied the prize.”

Joel B. Pollak is Senior Editor-at-Large at Breitbart News. He was named one of the “most influential” people in news media in 2016. He is the co-author of How Trump Won: The Inside Story of a Revolution, is available from Regnery. Follow him on Twitter at @joelpollak.