While eating dinner on a cold February night in 2007, I received an impassioned phone call.

“Pat, this is Stokes. You know my dream has always been to be a Marine. I need your help on something. I found out this week the Corps doesn’t want to extend my enlistment — they are going to kick me out. Can you write a letter of recommendation for my career placement officer? He said it might help, but I’m still probably going to get kicked out.”

I told him I would do all I could to help. When I hung up, I was furious. Sean Stokes was one of the finest Marines I had ever known. I witnessed him risking life and limb countless times. He deployed to Iraq twice, single-handedly killed nine insurgents, and was combat wounded twice. Now, he had to beg just to stay in the Marine Corps? My anger fueled my calls.

I met Sean in the heart of the Battle of Fallujah, among America’s most intense urban combat since Huế City. As one Marine put it, “If Fallujah isn’t hell, it’s in the same zip code.” I was a combat historian and fought house-to-house with Stokes’s platoon, as chronicled in my book We Were One. Resembling Luke Skywalker, this six-foot, blue-eyed, young Marine had tremendous personal presence and, above all, courage. I saw firsthand his fearlessness, and he displayed, over and over, his natural leadership.

On November 8, 2004, the Thundering Third assaulted the main defenses of Fallujah. The fighting was room to room, often hand to hand, against enemies who were hoping to be killed and only wanted to take Americans with them. Stokes’s First Platoon dropped from about 50 Marines to 14 in less than two weeks, including four Marines killed in action.

On the second day of the battle, grenade fragments ripped into Stokes’s arms and legs, but he was still able to function. He wanted to remain with his buddies, so Stokes hid his wounds to avoid mandatory evacuation. Over the next nine days he led the fight through the endless rows of houses and bunkers.

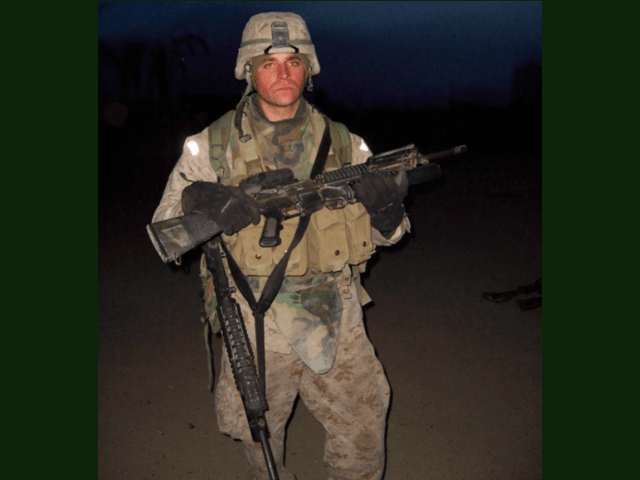

On November 17, Stokes, along with most of First Platoon, was lured into a sophisticated ambush in two adjacent but connected houses. Inside one of the houses, Stokes was thrown back six feet by an enemy fragmentation grenade that detonated next to his body. He was trapped alone in the ambush house with the jihadists. “As I got up, rounds started impacting near me down the hall. The fighters kept coming closer, closer,” Stokes recalled. “I was firing at the Chechens who were getting closer.” Foreign fighters in Fallujah hailed from at least 18 different countries; the Chechens were the best-trained, most deadly Islamist fighters in the city. Fighting was intense. A Marine sergeant near me was struck in the arm by machine-gun fire (see photo in this article) and the Marine in front of me was shot in the face. Hoping he was still alive, I carried the mortally wounded Marine out of the firefight.

“[As the Chechens charged,] my magazine went dry!” Stokes said. “Everything I did was by instinct, so I pulled out a grenade to frag the Chechens. I thought I was going to die; I was out of mags and they were just about to peek around the corner.”

Before the insurgents could kill Stokes, Lance Corporal Kramer bull-rushed a padlocked steel door and burst into the house, guns blazing. Kramer grabbed Stokes and carried him to safety. The Marines destroyed the houses with explosives and tank fire, killing the Chechens. Suffering from a concussion, yet lucid, Stokes refused to leave his fellow Marines and had to be ordered to the field hospital.

Stokes snuck out of the field hospital so that he could rejoin his brothers-in-arms as quickly as possible. A week later, he found himself in hand-to-hand combat with an insurgent, whom he dispatched with a trench knife.

Yet as a private, Stokes was the lowest-ranking member of First Platoon. Why?

Other men in the platoon explained that prior to 3/1’s second deployment to Iraq in the summer of 2004, then-Lance Corporal Stokes was court-martialed for leaving Camp Pendleton without permission.

Stokes had risked his dream and career to protect a loved one who was a victim of domestic violence. He found his family member a new place to live, returned to Pendleton, and asked for a second chance. He was demoted but temporarily allowed to stay in the Corps if he joined Lima Company, 3/1, which was about to deploy to Fallujah.

Stokes understood the risks of heading to Iraq. It was clear to most that a major battle for Fallujah loomed. He knew he would likely fight in Fallujah. But rather than dread the deployment, Stokes embraced it. “3/1 gave me another shot.”

Stokes responded to this second chance by becoming a model Marine during the following three years.

The story should have ended here, but Stokes’s AWOL would continue to haunt him. He returned to Iraq with 3/1 for his second tour. He volunteered to be a scout and led Lima Company into battle again. As usual, Stokes was out front.

After returning from Iraq from his second tour, Stokes spent the next few months at Pendleton preparing for his next deployment. Since fighting in Fallujah, he had been promoted to lance corporal and then to the rank of corporal, with sergeant right around the corner. He was devastated when he was informed that his enlistment would not be extended. While he debated leaving the Marine Corps and taking a real-estate job, he called me and told me his heart was in the Marine Corps.

Eventually, Stokes was offered a ten-month extension if he would deploy to Iraq a third time. It was a temporary assignment, and he would serve as the battalion commander’s personal security.

Several officers told me flatly that Stokes’s chances of staying in the Corps after the temporary 10-month deployment to Iraq were practically nil. The Commandant of the Marine Corps would have to approve it, and Marines with similar incidents to Stokes’s AWOL were being let go.

One officer stated bluntly, “His only chance is if we get him the medal he deserves from Fallujah. With a combat decoration in his file, there’s a tiny chance he might be able to stay in.” In my 25 years of conducting interviews with thousands of WWII and Iraq veterans, it was one of the most compelling cases for receiving the Bronze Star I had ever seen. The combat version of the medal is awarded to servicemen who distinguish themselves by courage under fire. Stokes clearly went beyond the call of duty and the requirements for the medal. I wrote a letter detailing Stokes’s actions in Fallujah and the reasons he merited at least the Bronze Star. It also included a reference for his second Purple Heart, which he should have received for the wounds he hid at the beginning of the battle.

Initially, I did not tell Sean about the medal recommendation. I did not want the members of the medal committee to think Stokes was in some way trying to influence his own award. As the USS Bonhomme Richard was pulling out of port with the Thundering Third on board, bound for the unit’s fifth combat deployment to Iraq, Stokes called me to inform me he was leaving for Iraq. In a final act of selflessness, to spare his family the anguish of deployment, he never told them he was heading to Iraq.

Sergeant from 1st Platoon wounded in Chechen ambush in Fallujah on Nov. 17, 2004 (Photo Credit Patrick K. O’Donnell)

Weeks passed, and I had not received a response on the medal. I found out that the “award authority” had expired; therefore, the battalion was highly unlikely to approve it. Though progress on the medal had stalled, one officer suggested I create a paper trail. Sean emailed me to let me know he was moving from Kuwait to Iraq the next day and asked whether I or any of the officers had written on his behalf to the Marine career planner. Out of frustration and because I did not want him to think I failed him, I emailed him the Bronze Star recommendation letter. Stunned, he wrote back, “Wow, I don’t deserve that… I just got off a four-day training op in Kuwait. So sorry it’s taken so long to respond, but here I am. I can’t thank you enough for that, but I don’t deserve it. The guys who deserved medals got them and I got to live on…that’s my medal.”

While leading 3/1’s personal security detachment on a combat operation outside Fallujah, an honor reserved for the most elite Marines, on July 30, 2007, Sean was slain by two 155mm artillery shells that were daisy-chained together, forming an IED. The force of the blast hit Sean, saving the life of his battalion commander, whom Sean was protecting. Minutes later, Corporal Sean Stokes died in his battalion commander’s arms. Sean Stokes received his third Purple Heart and later the Silver Star for his actions in Fallujah. He will be a Marine forever.

Patrick K. O’Donnell is a bestselling, critically acclaimed military historian and an expert on elite units. He is the author of eleven books, including We Were One, which was on the Commandant’s Professional Reading List. The Unknowns is his newest. He will be the keynote speaker for National Purple Heart Day at Mount Vernon. O’Donnell served as a combat historian in a Marine rifle platoon during the Battle of Fallujah and speaks often on espionage, special operations, and counterinsurgency. He has provided historical consulting for DreamWorks’ award-winning miniseries Band of Brothers and for documentaries produced by the BBC, the History Channel, and Discovery. PatrickkODonnell.com @combathistorian

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.