The Necessary Mission to Moscow

The President of the United States is under fire for being too close to Russia; he is now being attacked daily for being too helpful to that country in a time of crisis.

One Senator, a member of the President’s party, warns that the administration’s Russia policy exceeds its constitutional authority; the lawmaker says he is dead-set “against every step which gives dictatorial powers to the President.” The Senator adds, “Never before has a Congress coldly and flatly been asked to abdicate.” In the meantime, a Congressman says dismissively of the man at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, “Let the President clean his own house; quit issuing half-truths.”

A second Senator says angrily of entanglement with Russia,“I care not for Russia and Russia’s greed,” warning the President, in the starkest possible terms, against any partnership with Moscow: “Do not plunge this country into that sort of holocaust.”

Yet the President, born and bred a wealthy New Yorker, doggedly insists on continuing his pro-Russia policy, declaring publicly, “It is our duty, as never before, to extend more and more assistance and ever more swiftly to . . . Russia.” In fact, the President has also communicated privately to the Russian leader, promising to keep working “to assure you of our great determination to be of every possible material assistance.”

Does all this seem familiar? Were you thinking maybe that this is a description of the year 2018, as the 45th President, Donald Trump, pursues his controversial Russia vision?

Well, actually, Virgil was recalling criticism of the 32nd President, Franklin D. Roosevelt during the first eleven months of 1941, January to November—that is, the fraught period just prior to Pearl Harbor. (For the historically curious, the links to all of FDR’s comments can be found here.)

American President Franklin Delano Roosevelt (1882 – 1945) declares an ‘unlimited’ national state of emergency over the radio in response to German aggression during World War II, Washington, D.C., May 27, 1941. (Photo by FPG/Getty Images)

Indeed, a look back at history—at the choices made by FDR in 1941—provides useful perspective for today, because it casts light on the choices being made by Trump in 2018.

How so? One big reason is that then, as now, the U.S. President has had to consider the possibility of working with Russia—repugnant as that country’s regime was, and still is—in order to build a coalition against an even greater threat. That is, the Commander-in-Chief must see if it’s possible to include Russia in a coalition that would serve the ultimate national-security interests of the United States. In 1941, that greater security threat was Nazi Germany; in 2018, it’s the People’s Republic of China.

Americans have been slow to realize the threat from China. After all, it wasn’t that long ago that President Bill Clinton proclaimed that he was engaging China in a “constructive strategic partnership.” And of course, the Clinton, Bush 43, and Obama administrations were always touting ever more “free trade” with China.

Yet in recent years, Americans have been waking up. During the 2016 campaign, Trump accused China of “raping” the U.S. on trade, and today, of course, U.S.-China trade relations are a flashpoint. Indeed, the whole world is waking up to China’s rapidly expanding military, economic, and geopolitical power.

Perhaps most urgently, Chinese spies and hackers have been penetrating deeply. In his July 18 testimony on Capitol Hill, FBI Director Christopher Wray said that while the Russians have been an “aggressive actor,” it’s the Chinese who are the real danger. As Wray put it, “I think China, from a counterintelligence perspective, in many ways represents the broadest, most challenging, most significant threat we face as a country.”

One leading American figure who has been sounding the China alarm loudly is Stephen K. Bannon, the former Trump White House adviser and former Breitbart News chief. Bannon is not unmindful of the threat from Russia, and yet he is more mindful of the much greater threat from China; after all, China has 10 times the population, and 10 times the GDP, of Russia. And of course, whatever the Russians can do, hacking-wise, the Chinese can do more—and, indeed, they are doing more.

So with that in mind, Bannon urges a revised geopolitical strategy. That is, if China is the greater risk, then Americans should adjust their thinking accordingly. As Bannon told CNBC on July 18, we’re already in an “economic war” with China.

That same day, a headline in the British Spectator summed up another key part of Bannon’s message: “‘We have to end the Cold War with Russia’: The former White House strategist thinks China poses a much greater threat.” As Bannon told the magazine, Russia is a “kleptocracy . . . not good guys,” and yet still, “we have to bring Russia into some sort of alliance or rapprochement with the West.” That is, pull Russia into some sort of working relationship.

In fact, the Russians have always been suspicious of China; the two countries are natural rivals for dominance on the Eurasian land mass, and they have fought innumerable battles and skirmishes along their extensive borderlands, including as recently as 1969. To this day, the Chinese claim extensive Russian territories as their own; in fact, much of what the Russians call “Siberia” is known to the Chinese as “Outer Manchuria.”

So yes, it should be possible, as well as desirable, for the U.S. to enlist Russia into a China-containment policy. Yet if such a cordon sanitaire cannot be established, and if Russia were to slip into the Chinese orbit, well, that would spell bad news for the U.S.; the prospect of a Eurasia united in anti-Americanism would be scary, indeed. As Bannon says grimly, if Russia were ever to partner “with this [China-led] axis, the 21st century will be quite different.” That is, for America, quite worse.

In the meantime, Trump is determined to ride out the controversy over his Russia policy. As the President tweeted on July 18, “Some people HATE the fact that I got along well with President Putin of Russia. They would rather go to war than see this. It’s called Trump Derangement Syndrome!” And the following day, he added, “The Fake News Media wants so badly to see a major confrontation with Russia, even a confrontation that could lead to war. They are pushing so recklessly hard and hate the fact that I’ll probably have a good relationship with Putin.”

In fact, Trump’s outreach to Russia is already paying dividends, as attested by this July 20 headline in The Washington Post: “Inside the Putin-Netanyahu-Trump deal on Syria.” As the article details, the three leaders—Russia’s Vladimir Putin, Israel’s Binyamin Netanyahu, and Trump—seem to have worked out a deal on Syria, which, among other things, gives Israel the right to strike at Iranian targets in that country. As the picture of Netanyahu and Putin shaking hands, all smiles, suggests, the Israelis, at least, seem quite pleased. (Yes, it’s a bit odd that the Post, which normally spends 99 percent of its time trashing Trump, would run an article demonstrating that he’s actually accomplishing things; we might say that this pro-Trump piece was a one-off, even as, of course, the underlying reality of a deal over Syria is more important than any mere gaggle of headlines.)

Russian President Vladimir Putin shakes hands with Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, right, during their meeting in the Novo-Ogaryovo residence, outside Moscow, Russia, Monday, Sept. 21, 2015. (AP Photo/Ivan Sekretarev, Pool)

The Hard Choice Made by Churchill and Roosevelt

So with the realization that a diplomatic understanding with Russia can be valuable, even vital, it’s worth looking back to the diplomacy of the early 1940s, to a time when Uncle Sam and the Russian Bear found common ground at a time of extreme crisis. As we shall see, that ground was always unsteady, even rocky—and yet the cooperation that was achieved saved America and the world.

We can begin with the events of August 23, 1939, when Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia reached an agreement—the so-called Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact—with each other. The leaders of the two countries, Adolph Hitler and Josef Stalin, were hardly friends; indeed, the two men had never so much as met each other. And yet the Hitler-Stalin entente was a big deal, because it enabled both dictators to pursue their respective plans of conquest.

Réunion entre le bras droit de Staline Viatcheslav Molotov et Adolf Hitler, circa 1930. (Photo by Keystone-France/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images)

So on September 1, 1939, Hitler, flagrantly violating numerous treaties, invaded Poland. In response, Britain and France loyally, albeit reluctantly, declared war on Germany. The two Western countries had no chance of actually defending Poland from the blitzkrieg onslaught, but it was the right thing to do.

Then, astonishingly, after the German Wehrmacht had mostly destroyed Poland’s defenses, the Red Army attacked from the east. As a result, Poland disappeared from the map, brutally partitioned by its two neighbors.

We might now pause to consider the geopolitical situation as it must have appeared to London or Paris in 1939: The terrible dictators, Hitler and Stalin, each boasting huge armed forces, were teaming up on nasty conquest. From the point of view of liberal democracy, it’s hard to think of a worse situation—the bad guys, united, vastly outnumbering the good guys.

Then the situation got worse: In late 1939, the Soviet Union attacked Finland. Only the gallant defense of the Finns, fighting bravely in the wintery forests they knew well, staved off the complete subjugation of that country. Instead, the Finns suffered only a partial defeat.

For its part, Germany was even busier—and more effective. In May-June 1940, the Nazi military overran most of Western Europe, including France. Those German victories were so staggering that the world hardly noticed the smaller Soviet wins in the meantime: The Russians invaded and occupied the three Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania.

To look at a map of Europe in mid-1940 is to see that Churchill’s England was, well, alone. As a pair of Oscar-winning movies reminded us last year, this was Britain’s darkest hour, and yet, at the same time, one of its finest hours.

Yet even as Churchill was proving himself to be a determined war leader and inspirer of the human spirit, he was nonetheless a realist. He could see that both Hitler and Stalin were malevolent, and yet he saw that of the two, Hitler was worse—and this at a time when nobody yet knew the full depths of Hitler’s evil; his greatest crimes were still to come.

So to preserve Britain, Churchill had to make a choice. That is, he had to decide to to oppose one dictator, but not both. If Hitler was the urgent threat, well, then, Hitler was the enemy—an enemy to be fixated on, with relentless focus. And as for Stalin, well, by default, if he wasn’t the enemy, then he was, at least potentially, a friend.

This was a hard choice for Churchill, and yet in the world of high-stakes statecraft, all big choices tend to be hard choices. And once he had made his choice, Churchill was both resolute and articulate, quipping, “If Hitler invaded hell I would make at least a favorable reference to the devil in the House of Commons.”

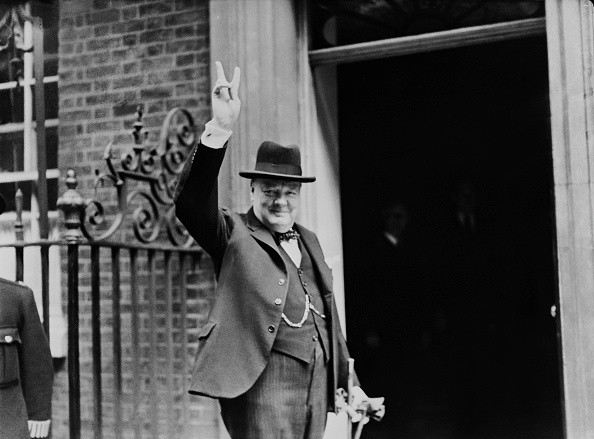

Prime Minister Winston Churchill outside 10 Downing Street, gesturing his famous ‘V for Victory’ hand signal, London, June 1943. (Photo by H F Davis/Topical Press Agency/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

So where was the U.S. at this time? As we know, the Yanks had come to the aid of Britain and France in World War One, and yet the disappointing aftermath of the Versailles peace proved to be deeply disillusioning to Americans. Even two decades later, according to the polls, majorities in the U.S. wanted nothing to do with a second European war.

For his part, President Roosevelt could see that a war with Germany was likely, like it or not. As far back as 1937, he had argued in favor of a heavily armed stance for the U.S.—he called it a “quarantine”—aimed at mostly Nazi Germany, but also at Fascist Italy and Imperial Japan.

Yet many well-placed American observers thought that Germany was unbeatable. One such was the famous aviator Charles Lindbergh; he had traveled to Germany, schmoozed with top Nazis, and reported back to America that German aviation would give that country a decisive edge in any conflict. Indeed, Lindbergh’s wife, Anne Morrow Lindbergh, went even further; in 1940, she published a best-selling book, The Wave of the Future, predicting, in glowing terms, a fascist destiny for America.

So we can see: In 1940, it wasn’t at all obvious that the U.S. could even survive as a free country, let alone prevail in a second world war.

And yet Roosevelt knew that America needed to do more than just await a bitter fate. On June 10, 1940, even as the Nazis were storming into Paris, FDR spoke at the University of Virginia, explaining that isolationism was not an option; as he put it, some Americans “still hold to the now somewhat obvious delusion that we of the United States can safely permit the United States to become a lone island, a lone island in a world dominated by the philosophy of force.” (Only years later did we learn that Hitler, in fact, had every intention of someday attacking the U.S. in North America.)

Yet even so, FDR knew that, powerful as he was, he could still only nudge, not shove, public opinion. So he used the bully pulpit: On December 29, 1940, he delivered one of his “fireside chats”—only this chat was anything but cozy. Describing the ominous world situation, he warned:

…If Great Britain goes down, the Axis powers will control the continents of Europe, Asia, Africa, Australasia, and the high seas—and they will be in a position to bring enormous military and naval resources against this hemisphere. It is no exaggeration to say that all of us, in all the Americas, would be living at the point of a gun—a gun loaded with explosive bullets, economic as well as military.

As he spoke of guns and bullets, FDR had a plan. And that’s why that December 29 address is remembered for the vivid phrase, “arsenal of democracy.” Virgil will take up that mighty subject in Part Two.

This is the first of three parts. Next: Using Russia to overcome the greater foe.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.