In today’s mainstream media, the most common label to slap on anyone who is not a self-confessed liberal is “far right,” despite the fact that most opinions associated with this “far right” were commonly held less than a generation ago.

On Saturday, NBC News ran an article calling Candace Owens — the bright, telegenic, African American conservative — the “loudest voice on the far right.” It is, of course, unthinkable — the logic runs — that a young, smart, black woman reason for herself and step out of sync from the groupthink that African Americans are regularly told they must espouse.

This week, Truthout.org echoed the liberal characterization of the Patriot Prayer group as “far right,” presumably because the Portland, Oregon-based organization advocates free speech for all and declares itself pro-family and a defender of the First Amendment.

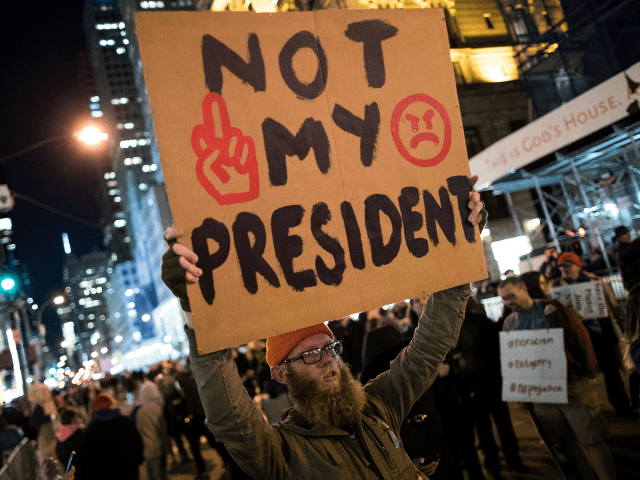

Virtually anyone who voted for Donald Trump in the 2016 presidential election is necessarily branded as part of the “far right,” despite the fact that the numerical mass of people encompassed within this group would seem to defy this adjective since “far” anything usually denotes a numerically tiny fringe.

The “far right” label is not reserved for Americans, of course, and is regularly used to describe members of populist and pro-sovereignty parties and movements in Italy, Austria, France, Germany, Hungary, and even Sweden. As soon as a party questions the logic behind open borders and mass immigration, for instance, it becomes “far right” by default.

In Italy, Interior Minister Matteo Salvini is regularly described as “far right” by establishment media because he balks at the idea that Brussels should be telling Italians how to run their country, a scenario mirrored in the Hungary of Viktor Orbán. This happens despite the fact that there are several parties clearly to the right of Salvini’s League and that he ran, and came to power, under the banner of “center right.”

In the United Kingdom, it is sufficient to have supported the Brexit vote to be tarred as “far right” because — the left seems to suppose — any rational person would have wanted to stay in the European Union. The fact that the Brexit referendum passed by a majority seems an unimportant detail to those who are determined that anyone to the right of them must be “far right.”

The question presents itself as to why establishment media insist on using the language of “far right” to describe their ideological opponents.

The answer is twofold: political and linguistic.

First, calling a person, movement, or party “far right” immediately conjures up images of swastikas, brown shirts, and Nazi salutes. This has been particularly effective in Germany but is employed to formidable effect elsewhere as well. Even the ultra-violent Antifa movement in the United States — whose members wear black masks and cudgel innocent citizens on the streets — had the good political sense to names themselves in opposition to fascism, another buzzword meaning anybody who is not a socialist.

To be politically “far right” then is to be dangerous, villainous, anti-Semitic, and quite probably demonic.

The second reason that the establishment insists on using the term “far right” is to try to pigeonhole their adversaries as radical extremists, far removed from the acceptable “center.” The “far right” is worse than “right” (which is bad enough) and brings to mind cultish practices and conspiracy theories worthy of Mel Gibson’s brilliant opening scene in the movie of the same name.

If cultural ideology runs a spectrum from left to right, then the “far right” must be somewhere off in the distance in mountain villages where men still marry their sisters.

The bright side to all of this name-calling, however, is that the left has overplayed its hand. Anyone who has ever heard Candace Owens speak (and this includes hundreds of thousands, if not millions) knows full well that there is nothing “far right” about her, and the term itself begins to lose its impact.

Hearing that Trump voters are all “far right” may ring true to the ears of certain tone-deaf coastal elites but sounds ridiculous both to the millions of Trump voters themselves and to their families and friends.

The trouble with relying on labels in place of arguments is that they eventually lose their force, and when that happens, reasoned argument has a way of moving back toward center stage.

Follow Thomas D. Williams on Twitter Follow @tdwilliamsrome.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.