There are certain words and terms in the English language that carry negative connotations and conjure unfavorable images in peoples’ minds, regardless of the facts or contexts in which the terms are used. One such term is “assault weapon.”

Gun control activists long ago discovered that if they use the term “assault weapon” to describe a firearm, the vast majority of people reading or hearing such term, will picture in their mind a rifle capable of fully automatic fire; this despite the fact that private possession of fully automatic firearms has been essentially unlawful for more than eight decades.

The gun control movement’s love affair with the term “assault weapon” began in the mid-1980s in California. On July 18, 1984, one James Huberty murdered 21 individuals (and injured many more) at a fast-food restaurant in San Ysidro. None of the three firearms he used for his horrendous killing spree was capable of fully automatic fire; thus, none was an “assault weapon” as the term had for decades been used to describe military firearms having that capability. Still, the term provided sufficient emotional horsepower for gun control legislators in California to ban civilian, semi-auto “assault weapons” five years later, in 1989.

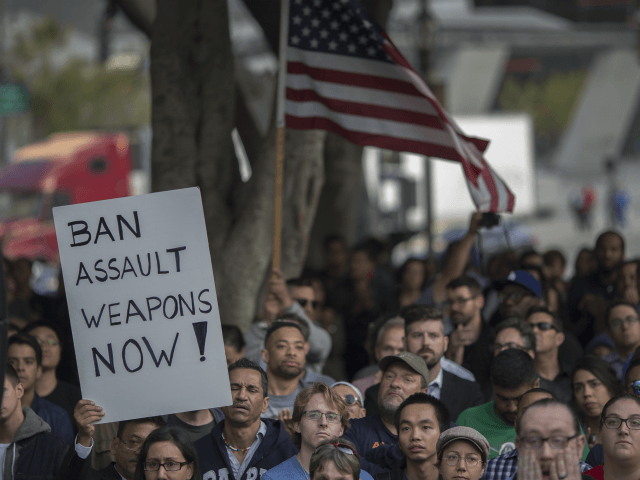

The romance blossomed in the mid-1990s, when Congress enacted a ten-year federal ban on “assault weapons.” In recent years, almost always spurred by a mass murder involving firearms, several states have passed laws banning such firearms.

In every instance in which federal or state officials have moved against “assault weapons” legislatively, the language follows the same narrative: “These are weapons of war that are made for the sole purpose of killing as many people as possible as quickly as possible. These weapons are not used for hunting or any legitimate purpose.” Etc. Etc. Etc.

Relentless use of the term “assault weapon” to color and, in many respects, define the gun control debate over the past three decades, has served the movement well. It greatly facilitates debate that otherwise would force voters and legislators alike to actually understand that there in fact is a significant difference between civilian, semi-automatic versions of military rifles, and those used by the military and law enforcement that may look the same but possess the ability to fire in full automatic mode.

Keeping the debate focused on the false narrative that “assault rifles” have no purpose other than mass murder, makes it easy to skip over the facts that rifles such as the civilian AR-15 often are used in legitimate rifle competition and for hunting. This is because the rifle is extremely accurate. Such rifles also have been used effectively for home defense, as was established as early as 1995 during House Judiciary Committee hearings in which I participated.

The Parkland, Florida school shooting last February — in which the killer used a civilian, semi-automatic version of the military’s M-16 automatic rifle – has ratcheted the rhetoric to a new, fantastical level. California Congressman Eric Swalwell, a glib but photogenic gun-control champion, wrote recently in USA Today that such “hand-held weapon[s] of war” must be banned nationally. He called for billions of taxpayer dollars to be used to buy back all such rifles currently owned lawfully by citizens across the country (up to 15 million by some estimates). In Swalwell’s mind, such measures are easily justified because of the enhanced public safety such moves would ensure.

Except for one thing — measures such as banning the AR-15 and buying back all such rifles would ensure nothing.

For starters, the vast majority of crimes committed with firearms in the U.S. are committed with handguns, not rifles of any configuration; by a ratio of about 19 to 1. And of crimes committed with rifles, hardly any perpetrators used AR-15-type rifles.

So, do gun bans work as a method of reducing gun crimes generally or mass shootings in particular? The 1994 federal “assault” weapons ban in the U.S. did not; and similar bans in European countries have not done so either.

Do gun buy-backs, as Congressman Swalwell favors, work? No. The nationwide, mandatory gun buy-back program in Australia in 1996-97 actually had a reverse effect, as noted by well-known firearms analyst John Lott. Writing this past February, just days after the Parkland tragedy, Lott’s research revealed that the armed robbery rate in the “Land Down Under” rose dramatically following the buy-back program. The explosion in armed robberies declined only after Aussies began once again to buy firearms for protection in the years after the buy-back.

So if gun bans and buy-backs don’t serve to reduce crime and enhance public safety, what purpose do they serve? Simple. Such proposals serve as talking points for those politicians whose thirst for control remains focused on the one aspect of American society that has served as a bedrock of individual liberty since the Bill of Rights was ratified in 1791 – the right to keep and bear arms.

Bob Barr is president and CEO of the Law Enforcement Education Foundation (LEEF). From 1995-2003, he represented Georgia’s Seventh Congressional District in the U.S. House of Representatives.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.