Most Americans think of General George S. Patton as the great commander of U.S. forces in North Africa and Europe in World War II, but fewer know that the colorful and charismatic officer also played a key role in World War I — and here he learned to command.

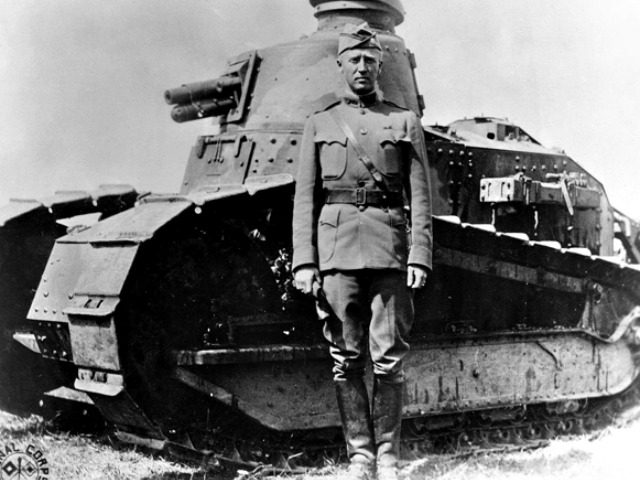

One hundred years ago, in the summer of 1918, Patton led 144 FT-17 tanks into battle against the Germans near St. Mihiel, France. The Americans’ goal was to reduce a salient, a bulge in the lines where the enemy had pushed into Allied territory.

Ahead of his time, Patton recognized that tanks would one day be a tremendous force on the modern battlefield, and he had been largely responsible for establishing and training the country’s nascent tank force. The U.S. relied heavily on the French-made Renault FT-17, a revolutionary vehicle that was the first to feature a fully rotating turret and have the crew compartment up front and the engine in the back. Sixteen feet long and about six feet wide, the FT-17s were nimble enough to navigate French forests and eliminate German machine-gun nests while their armor plating protected the crew inside.

However, WWI technology didn’t always meet expectations. The light tanks frequently became enmired in the muck surrounding the trenches, halting forward progress while they waited for the combat engineers who escorted them to extricate them from the morass.

For the always irascible Patton, the picture of these magnificent war machines stuck in the mud near St. Mihiel “was a most irritating sight.” He decided to take his frustrations out on an American infantryman they passed. “I saw one fellow in a shell hole holding his rifle and sitting down,” Patton later wrote. “I thought he was hiding and went to cuss him out.” But when he got close to the man, the officer discovered that the soldier was dead with a bullet over his right eye.

Other men might have found the grisly sight disturbing, but not Patton. “The more one sees of war, the better it is,” he wrote in a letter to a friend. “Of course there are a few deaths but all of us must ‘pay the piper’ sooner or later and the party is worth the price of admission.”

Some of Patton’s experiences in World War I are retold in my new bestselling book, The Unknowns: The Untold Story of America’s Unknown Soldier and WWI’s Most Decorated Heroes Who Brought Him Home. Released in May, The Unknowns follows eight American heroes who accomplished extraordinary feats in some of the war’s most important battles. As a result of their bravery, these eight men were selected to serve as Body Bearers at the ceremony where the Unknown Soldier was laid to rest at Arlington Cemetery.

One of those Body Bearers, Corporal Thomas Saunders, served in the 2nd Combat Engineers near Patton’s tanks at St. Mihiel. Another Body Bearer, Sergeant Samuel Woodfill, fought near Patton in the Meuse-Argonne in September 1918. Then a lieutenant colonel, Patton commanded the 304th Tank Brigade in the Meuse-Argonne and planned to use his armor in a concentrated force to sweep in and annihilate the enemy. But as at St. Mihiel, the tanks ran into difficulty with the terrain.

Exasperated, Patton climbed down from the tank where he was riding and marched up to the front of the line to see why the column had stopped moving. One of the tanks had been unable to cross a ditch, and with the enemy artillery zeroed in on the location, the men had taken shelter rather than working to extricate the vehicle.

Patton had no such qualms about being in the line of fire. He immediately ordered a crew of men to join him in getting the tank past the obstacle. When one man balked, Patton hit him on the head with a shovel. He later said that might have killed him — he didn’t know for sure.

The incident was in keeping with one of Patton’s mottoes: “A good plan, violently executed now, is better than a perfect plan next week.”

When at last the tank was free and the column was moving again, Patton decided to continue on foot, despite the nearly constant machine-gun fire.

“To hell with them,” he said aloud. “They can’t hit me.”

But when the torrent of bullets intensified, Patton momentarily became overcome with fear. He dropped to the ground trembling. At that moment he remembered the generations of his ancestors who had given their lives for their country. “It is time for another Patton to die,” he decided.

The lieutenant colonel called for volunteers, and six men came forward. Patton led them straight into the thick of the battle as he directed the movement of his tanks. One by one, five of those volunteers fell, killed by enemy fire. Eventually, even Patton had to stop after a bullet struck his thigh and exited through his buttocks. But rather than allow himself to be taken to the field hospital, he stayed on the scene and continued giving orders, directing his tanks to eliminate the German machine-gun nests so the other Americans could advance.

The Meuse-Argonne would be Patton’s last chance to fight in World War I — much to his dismay. From his hospital bed, Patton wrote to his wife, “Peace looks possible, but I rather hope not for I would like to have a few more fights. They are awfully thrilling, like steeple chasing, only more so.”

Throughout his life, he saw himself as the representative of a great line warriors stretching back for generations. He believed it was his duty to fight violently on the battlefield and then conduct himself with decorum when off it. Addressing young officers after the end of World War I, he said, “Does it not occur to you gentlemen that we, as officers of the Army … are also the modern representatives of the demigods and heroes of antiquity? … In the days of chivalry, the golden age of our profession, knights (officers) were noted as well for courtesy and being gentle benefactors of the weak and oppressed. … Let us be gentle. That is courteous and considerate for the rights of others. Let us be men.“

He was perhaps the most striking example of a generation of soldiers who put duty above all else. Shortly before his death in 1945, Patton summed up his thoughts on the subject when speaking at an Armistice Day event. “I consider it no sacrifice to die for my country,” he said. “In my mind we came here to thank God that men like these have lived rather than to regret that they have died.”

Patrick K. O’Donnell is a bestselling, critically acclaimed military historian and an expert on elite units. He is the author of eleven books. The Unknowns is his newest, released in May. O’Donnell served as a combat historian in a Marine rifle platoon during the Battle of Fallujah and speaks often on espionage, special operations, and counterinsurgency. He has provided historical consulting for DreamWorks’ award-winning miniseries Band of Brothers and for documentaries produced by the BBC, the History Channel, and Discovery. PatrickkODonnell.com @combathistorian

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.