This year marks the one hundred year anniversary of some of America’s most important battles in World War I. In many ways, it has become a forgotten war, although the fighting and its aftermath defined the twentieth century and continue to shape our world today. As Memorial Day approaches, this a fitting time to reflect upon the achievements of one of the forgotten war’s forgotten heroes, Edward Younger.

Younger’s story is retold in a new bestselling book, The Unknowns: The Untold Story of America’s Unknown Soldier and WWI’s Most Decorated Heroes Who Brought Him Home by Patrick K. O’Donnell. Released in May, The Unknowns follows nine American heroes who accomplished extraordinary feats in some of the war’s most important battles. As a result of their bravery, eight of these men were selected to serve as Body Bearers at the ceremony during which the Unknown Soldier was laid to rest at Arlington National Cemetery. The ninth, Sergeant Edward Younger, had the honor of selecting the body that would become the Unknown Soldier.

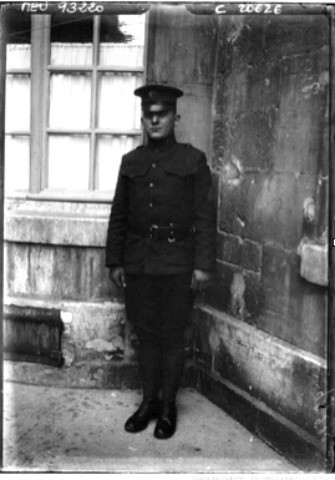

Born in Chicago in 1898, Younger was a somber, stocky man of average height, who had attended school only through the eighth grade. In February 1917, at the age of eighteen, he joined the U.S. Army “just out of excitement—or curiosity maybe.”

The following year, he found himself in the thick of the action. On July 1, 1918, Allied artillery began a barrage on the German-held town of Vaux near Belleau Wood, France. As evening fell, Younger’s 9th Infantry and other units swarmed the city. In the desperate fighting that ensued, Younger received multiple gunshot wounds to his head, neck, and left arm. Miraculously, he made a full recovery.

It would not be the last time.

He sat out as his company battled in Soissons but was back in action by September. While still recuperating, he led more than 60 men over the top and through no-man’s land to attack the Germans in the trenches of St. Mihiel. He and his men participated in the assault and capture of the village of Thiaucourt, now the location of a major American cemetery.

Then, just a few weeks later, they took part in the battle of Blanc Mont Ridge. Younger and the other Americans were tasked with a seemingly impossible mission: clearing the Germans from high ground where they had constructed an ostensibly impregnable fortress. Hundreds of machine-gun nests, an intricate maze of trenches, concrete blockhouses, artillery pieces, and tangled masses of barbed wire awaited any force foolish enough to attack. Thousands of Frenchmen had died while attempting to take the crest over the last three years of the war, and their remains littered the battlefield that Younger traversed.

From the moment their feet hit the ground, Younger’s company took fire. Leading the way, they charged up the ridgeline to the crest, where they hoped to link up with other Allied units. The Americans accomplished their goal, capturing the ridge and forcing the Germans to retreat in one of the most incredible feats of arms on the Western Front. But they took heavy casualties, including Younger, who would spend weeks healing from a machine-gun bullet in his thigh.

The indomitable American would recover again and participate in the last battle of the war, less than 24 hours from the signing of the armistice that ended hostilities. He survived one of the war’s most brutal — and tragic — battles, but what would be arguably his biggest contribution to America’s participation in World War I was yet to come.

In 1921, grass roots activism led to calls for America to create a memorial to honor the unknown soldiers who had perished in the fighting and were unable to be identified. Several European countries had created similar monuments, and the nation demanded an opportunity to remember and mourn its sons who lay in unmarked graves so far from home.

A general officer was originally going to select the Unknown Soldier, but a French official mentioned that his country had given the honor to an enlisted poilu (grunt). The Americans decided to follow suit and gathered a group of Doughboys, one of whom would choose the body to be buried in the monument.

The night before the selection, Younger and the others didn’t know which of them would be responsible for selecting the Unknown Soldier. They got little sleep “as the full meaning of our assignment bore in upon us,” Younger said.

The next morning, the men heard the news: Edward Younger would select the Unknown Soldier.

He later reflected, “I had gone over the top many times, had known the agony of waiting for the charge. But nothing had paralyzed me as that simple announcement did.”

As a military band played Chopin’s Funeral March, Younger slowly paced around four flag-draped caskets in the dimly lit city hall in Châlons, France. The American military had exhumed the bodies from four different cemeteries in France, including Thiaucourt where Younger had fought, taking special care to make sure that none of the corpses held any marks that could lead to identification. In his arms, Younger carried a clutch of white roses, which he was to place on whichever casket he selected.

Younger’s thoughts raced. He wondered if one of the men in the coffins before him could possibly be one of his own friends who had fallen in combat.

“I was numb. I couldn’t choose,” he recalled. “Then something drew me to the coffin second to my right on entering. I couldn’t take another step. It seemed as if God raised my hand and guided me as I placed the roses on that casket. This, then, was to be America’s Unknown Soldier, and by that simple act I had started him on his road to destiny.”

The Unknown Soldier would travel by ship to Washington, D.C., where tens of thousands of mourners would come to honor all the Americans who had fallen in battle. He was laid to rest at Arlington Ceremony in a moving ceremony. President Harding addressed the crowd, saying the Unknown Soldier’s “sacrifice, and that of the millions dead, shall not be in vain. There must be, there shall be, the commanding voice of a conscious civilization against armed warfare.” He added, “As we return this poor clay to its mother soil, garlanded by love and covered with the decorations that only nations can bestow, I can sense the prayers of our people, of all peoples, that this Armistice Day shall mark the beginning of a new and lasting era of peace on earth, goodwill among men.”

Edward Younger would spend the rest of his life trying — but often failing — to escape the notoriety he had achieved by selecting the Unknown Soldier. He returned home to Chicago, married, went to work in the post office, and raised a family. But every Memorial Day and Armistice Day, reporters would turn up, asking him to relive his glorious days of battle and the moment when he selected the Unknown Soldier.

Younger died in 1942 and was buried in Arlington National Cemetery, not far from the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier.

Today, this ordinary man who was selected as a symbol of the heroism of American Doughboys has achieved his dearest wish — almost no one knows his name anymore.

However, that seems a shame. Surely a man, who, like many of his generation, crossed an ocean to fight for his country and recovered from wounds time and again only to return to the battlefield, deserves our admiration and respect. This Memorial Day, it is fitting to honor the unknown hero who selected America’s Unknown Soldier.

Photos courtesy of The National Archives, Patrick K. O’Donnell

Patrick K. O’Donnell is a bestselling, critically acclaimed military historian and an expert on elite units. He is the author of eleven books. The Unknowns is his newest, which will be released in May. O’Donnell served as a combat historian in a Marine rifle platoon during the Battle of Fallujah and speaks often on espionage, special operations, and counterinsurgency. He has provided historical consulting for DreamWorks’ award-winning miniseries Band of Brothers and for documentaries produced by the BBC, the History Channel, and Discovery. PatrickkODonnell.com @combathistorian

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.