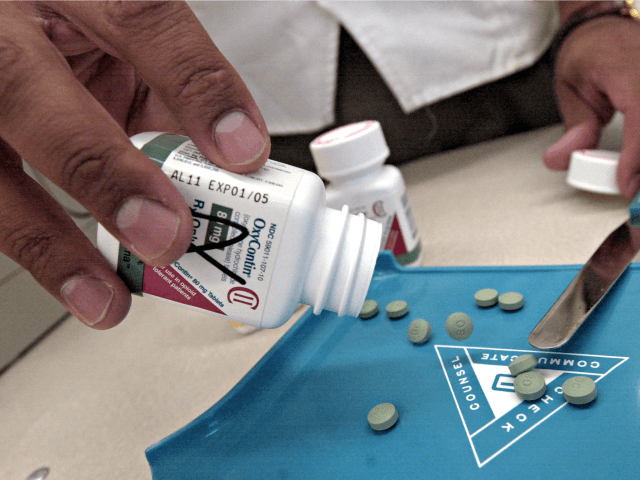

Determining the true cause of the opioid crisis is crucial – is it prescription painkillers or street drugs? Congress should not be passing legislation to solve the wrong problem. There will be serious public health consequences for cracking down on the wrong type of drugs.

The crisis will not abate if the real problem is not addressed effectively. There are good reasons to fear that special interests are pushing us in the wrong direction by targeting deep-pocketed pharmaceutical companies instead of elusive street dealers and foreign drug cartels.

A critical data point was provided by research confirming what police and doctors working on the front lines have said for years: the center of gravity in the opioid epidemic shifted from the overprescription and abuse of prescription painkillers to heroin and deadly fentanyl about a decade ago. If policymakers insist on treating pain medications as the more serious aspect of the epidemic, they will be making a grave mistake.

The skeptical position on our current drug war, stated bluntly, is that trial lawyers are eager to bring enormous lawsuits against pharmaceutical companies, and they have more than enough political influence to shape legislation. Many legislators prefer the narrative of rapacious Big Business getting the American people hooked on pills to reap windfall profits.

On the other hand, there is no money to be made by going after drug dealers and street gangs. There is no political profit from tightening border security to choke off the flow of drugs from Mexico and South America. Border security looks like all pain and no gain to politicians – they get hassled by activists, ridiculed as xenophobes by the media, and shunned by special interests. Fighting the War on Drugs is even more thankless, as clear-cut victory has proven elusive for decades.

One element of the opioid crisis is a problem the Washington elite loves to attack, while the other is something it doesn’t want to touch with a ten-foot pole. It seems reasonable to worry that the establishment will reverse-engineer a diagnosis that justifies the course of treatment it would much rather pursue.

Daniel Horowitz wrote in the fifth installment of his opioid series at Conservative Review that the danger of political misdiagnosis was the primary reason he set pen to paper (or keyboard to pixel, if you prefer):

The politicians are still blind to nature of the illicit drug/chemical warfare crisis in this country that they misleadingly refer to as a prescription opioid crisis. The good news is that Congress has made this issue the top legislative priority for the coming month. The bad news is that, as we have noted in our continuous series of articles, legislators are completely misdiagnosing the problem, ignoring the data showing both what the crisis actually is and what caused it. As such, their solutions are making the problem worse, as they focus exclusively on government practicing medicine, monitoring patients, restricting prescriptions and even morphine use in hospitals (not just outpatient prescriptions), and shoveling billions of dollars to special interest health care cartels to “treat” a problem they refuse to properly identify.

This week, four House and Senate committees will hold hearings and analyze over 30 pieces of legislation to address the “opioid crisis.” Almost all of the hearings, witness testimony, and legislation fail to address the core problems causing the alarming flood of illicit drugs: Mexican cartels, transnational gangs, open borders, and sanctuary cities.

Horowitz added that even the prescription drug side of the opioid crisis has been deliberately misunderstood for political reasons:

To the extent that this is a health care issue, they refuse to address the 800-pound gorilla in the room – the role of the Medicaid expansion fueling over-use of painkillers among Medicaid patients, a population inherently vulnerable to addiction, while they severely restrict use of much-needed painkillers for other patients.

At least one major government report, released by the Senate Homeland Security Committee in February, has examined the relationship between Medicaid expansion and increased levels of painkiller prescription and abuse, but it was resolutely ignored by the media and trashed as a cheap shot at Obamacare by Democrats.

Horowitz charges that the current round of congressional hearings on the drug crisis “feature heads of organizations and programs that stand to benefit from endless taxpayer funds,” while very little attention is paid to the politically awkward and unprofitable problem of drug cartels flooding America’s streets with heroin, fentanyl, and cocaine.

Meanwhile, a legal offensive comparable to the gigantic lawsuits against Big Tobacco is taking shape in the courts, led by some of the same lawyers and firms that went after the tobacco companies.

“The prospect of the biggest payday since the $200 billion tobacco settlement in 1998 has drawn many of the same plaintiff lawyers who appear again and again in big tort cases over everything from VW diesels to Vioxx to the BP Deepwater Horizon disaster,” Daniel Fisher observed at Forbes in January, as multi-district legislation against opioid manufacturers and distributors gained momentum.

Fisher quoted University of Georgia law professor Elizabeth Burch comparing the legal muscle behind these mega-lawsuits to an “oligopoly” and noting that “the same five lawyers are involved in practically every proceeding.”

Lawsuits against drug companies and distributors allege they have deceived the public on a massive scale with advertising for their products, flooded markets with opioids, pushed doctors to prescribe them, and failed to investigate illicit drug orders properly. The industry responded by accusing litigants of misunderstanding how the distribution system for prescription drugs works and turning pharmaceutical corporations into lucrative scapegoats.

On the legislative side, Senator Bernie Sanders (I-VT) introduced a bill this week targeting opioid manufacturers with $7.8 billion in fines for deceptive advertising and establishing criminal liability for corporate executives found to have “contributed to the epidemic.”

Sanders expressed a desire to extract even more money from the industry to deal with the drug crisis he accuses them of creating: “At a time when local, state and federal government are spending many billions of dollars a year, those people will be held accountable and asked to contribute to help us address the crisis. It shouldn’t just be the taxpayer that has to pay for the damage that they did.”

If Congress and the courts get the opioid crisis wrong, patients who truly need medication for chronic pain will suffer even more than they already do. They already complain that the drugs they need have been excessively stigmatized and doctors have been intimidated out of writing prescriptions.

The patients themselves resent being treated like drug addicts. They have good reason to fear their access to vitally needed medication will grow even more restricted, between heavy-handed legislation and lawsuits that could clobber drug companies with billions of dollars in damages and settlements. Insurance companies are in the mix as well, performing calculations of benefit and risk, including legal risk, that can contradict the judgment of physicians.

“I’m looked at as an addict. I feel this stigma every single day: you’re a chronic pain patient, you must be an addict,” fibromyalgia patient Edwina Caito told the IndyStar in November.

“Nobody is hearing us, because everyone on the no-opiate bandwagon is screaming the loudest and we don’t have a voice.” Caito added.

Some doctors are worried that severe new limits on prescription opioids proposed by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid will leave chronic pain patients unable to obtain the medications they need. Doctors who questioned the new limits said they could force patients to seek out more dangerous illegal substances to manage their pain or even drive them to suicide.

“People who are gonna use heroin and fentanyl are gonna go ahead and use it. People who are really dependent on opioids, because there is no access to treatment, they are gonna move on to heroin. Only set of people this is going to affect is a lot of people who are stable on this medications,” Yale University addiction medicine fellow Dr. Ajay Manhapra predicted in March.

In early April, officials with the Centers for Disease Control conceded that its 2016 guidelines on opioid prescription might have been based on flawed data. Specifically, the research supporting the guidelines was criticized for failing to distinguish between overdoses of legally obtained pain medication and deaths resulting from illicit heroin and fentanyl. The number of deaths attributed to prescription drugs in 2016 was almost doubled by this faulty analysis, according to doctors who believe the CDC should scrap its current guidelines completely and explain why the data was handled so badly.

None of this is meant to absolve drug companies of all possible misbehavior, argue that prescription drug abuse is no longer a problem at all, or dismiss all funding for addiction treatment as taxpayer money siphoned off by special interests. The point is that government at every level should examine the opioid crisis clearly and honestly, with the vision of lawmakers as unclouded as possible by big money or political narratives, before regulations are imposed and funds are allocated.

There are already too many examples of people suffering unnecessarily because the problem has been diagnosed incorrectly. There should be no room in this process for political narratives, hidden agendas, grandstanding, or blind panic.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.