The conventional wisdom on the opioid crisis is that prescription drug dependency was a major factor behind the surge of addictions and overdoses.

This belief was challenged by studies demonstrating that prescription drug problems from the 1990s and 2000s were fading before the current opioid crisis began, and the real problem today is with street drugs like heroin and fentanyl. New research highlights a very sharp dividing line between the earlier pill problem and today’s drug crisis: OxyContin was reformulated in 2010 to cut down on abuse, so addicts turned to heroin.

According to a study published by the National Bureau of Economic Research, the border between the two drug crises is as plain as day. OxyContin, perhaps the most widely abused of the opioid painkillers, was altered in 2010 to make it more difficult for abusers to break the pills down and inject or snort the powder.

The reformulation was considered highly successful. It was not impossible to abuse Oxy under the new design, but it was much harder. Crucially, the reformulation made it harder to overdose on the drug. Studies conducted over the next few years suggested a reduction in OxyContin abuse rates of over 60 percent. The epidemic of “hillbilly heroin,” as it was often called, was clearly declining.

Unfortunately, even in the earliest days of reformulated OxyContin, medical professionals saw the great danger of abusers moving to heroin to get their fixes. The demand for OxyContin on the street evaporated with remarkable speed, but doctors and police were astonished by the surge in demand for heroin. Tragically, beefed-up street distribution networks and supply chains stretching over the porous southern border stood ready to meet that demand.

“Fixing” OxyContin was supposed to cut the legs out from the opioid epidemic because people who slipped into abusing prescription drugs would be reluctant to buy heroin from gangsters. The disappointment from medical professionals as those hopes were dashed is palpable in interviews from 2010 and 2011.

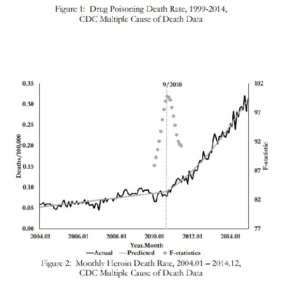

The NBER study uses a painfully clear graph to illustrate heroin overdose deaths skyrocketing within weeks of reformulated OxyContin hitting the market in the summer of 2010:

This is not the first study to establish a link between OxyContin reformulation and heroin abuse. Researchers from RAND and the Wharton School published a similar paper in January 2017. That paper looked at states with very high OxyContin abuse rates before 2010, and found that while abuse of the pills plummeted, the rate of overall opioid-related deaths did not decline at a similar rate.

A theory advanced in the study was that some people did escape from drug dependency once OxyContin became harder to abuse, but some of the remaining addicts turned to fentanyl, a synthetic opioid that is far deadlier than OxyContin or even heroin. This kept the rate of overdose deaths high. There were fewer addicts, but a higher percentage of them were killed by the drugs they transitioned to.

It is curious, and perhaps a bit suspicious, that drug policy remains driven by the perception that prescription drug abuse is the primary factor behind addiction and overdose deaths when that simply is not true any longer. The move to heroin and fentanyl has been common knowledge in the law enforcement and health care communities for years. Providers on the front lines expressed concerns that addicts were dropping OxyContin and moving to heroin within months of the 2010 reformulation. The latest research highlights a very clear line that everyone fighting the opioid crisis already knew was there.

“instead of reducing the addiction and death statistics, many addicts simply turned to heroin. It’s not only a lot cheaper than illicit OxyContin but a lot easier to come by,” the Novus Medical Detox Center wrote in April 2015, citing research available at the time.

“Prescription opiates can cost $30 or more per pill and a high-dose OxyContin pill often costs a lot more than that. But a hit of heroin can cost as little as $10 and you can find it on street corners all across America,” Novus pointed out.

This is not to say that prescription drug abuse, or disturbingly high rates of prescribed use, have completely disappeared. Some doctors expressed dismay that many addicts found ways to circumvent the reformulation of OxyContin and spread their techniques online, which may help explain why the reduction in abuse rates leveled out by 2014. There are still concerns that prescription drugs are a gateway to heroin for too many people. Pharmaceutical companies have been accused of helping to create the market for heroin and fentanyl by pushing pills to the previous generation.

The question is one of emphasis. If the current crisis has shifted so clearly to street drugs, are policymakers placing too much emphasis on pharmaceuticals? Is Washington fighting the last war because it’s not keeping up with current events? Is the federal government prone to treating the opioid crisis as a nationwide event instead of examining individual communities and regional trends? Is it easier for politicians to slam drug companies than talk honestly about street crime, illegal immigration, and the flow of drugs across the border?

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.