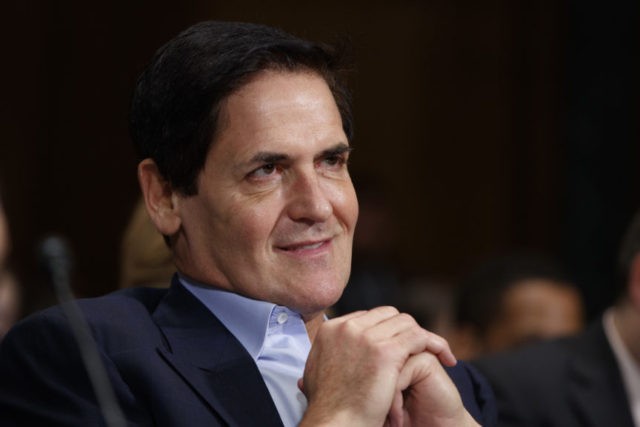

Mark Cuban is another brash billionaire with a popular reality-TV show, an active Twitter feed (7.6 million followers), a habit of giving punchy quotes to journalists, and, yes, national political ambitions.

These political ambitions, of course, have turned Cuban, once a friend of Trump, into his foe. And yet curiously, on key technology issues, the Dallas Mavericks owner is aligned with the 45th president. So if Cuban were himself ever to run for president, perhaps as soon as 2020, he’d be in the odd position of agreeing with his opponent on some hot topics.

To be sure, for the most part, Cuban has been distancing himself from Trump. In June 2016, he declared that Trump was getting “stupider before your eyes.” And in July 2016, he appeared at an event with Hillary Clinton and formally endorsed her, dismissing Trump as “batshit crazy.” Then, late in the ’16 campaign season, he appeared with Clinton again, this time saying of Trump, “You cannot be president of the United States if you don’t know when to shut up.”

Meanwhile, in 2017, Cuban has said that he is “considering” a presidential run, and he has been happy to see articles with headlines such as this, in the October 23 Washington Post: “Mark Cuban and Donald Trump, longtime frenemies, could face off in 2020 presidential race.” In that article, Cuban humble-bragged about his populist credentials:

You need somebody who can connect to people and relate to people at a base level and appreciate what they’re going through. I think I qualify on each of those.

So that’s Cuban’s self-declared persona: In his mind, he’s a populist billionaire, a rich man with the common touch; he likes to tweet, for example, inspirational tales about upwardly mobile entrepreneurs.

Okay, but what about his actual positions on issues? To put it mildly, Cuban’s agenda is unformed, although, of course, so was Trump’s at this point in the 2016 campaign cycle.

Still, we can learn a lot from Cuban’s Twitter feed. Not unlike Trump four years ago, Cuban weighs in on a wide variety of issues—although going in the opposite direction from Trump, having shifted to the left. For instance, he has retweeted strong defenses of Colin Kaepernick, and expressed skepticism about the Republican tax-cut plan.

Yet, bespeaking his own status as a Tech Lord—in 1999, Cuban sold broadcast.com to Yahoo for $5.7 billion—the bulk of his tweets concern tech issues. On the question of Net Neutrality, for instance, he has been supportive of at least the general course set by Trump’s Federal Communications Commission (FCC). So we can pause to observe that if Cuban is, in fact, positioning himself for a 2020 presidential run, he risks confusing his potential liberal supporters by aligning himself with Trump.

And perhaps even more interesting—and potentially wide-ranging in its political repercussions—is Cuban’s commentary on the recent action by the Department of Justice (DOJ) against AT&T’s proposed purchase of Time Warner. As Cuban tweeted on November 20:

I think the big losers of the DOJ suing to block the @ATT deal will be @FB and @Google. Their media advertising, content and distribution dominance will be a defense at trial. That could create bigger issues for them.

It’s worth unpacking this tweet, because it provides clues, not only about Cuban’s mindset, but also as to where the overall issue of the Tech Lords could be headed in the next few years.

As Cuban said in his tweet, DOJ’s action against AT&T will inevitably bring up other issues—that is, Facebook and Google could suffer collateral damage. That is, if AT&T is a target, then they, too, could be even bigger targets. As DOJ explained in its November 20 statement outlining its argument against the deal, “The $108 billion acquisition would substantially lessen competition, resulting in higher prices and less innovation for millions of Americans.”

AT&T Chairman and CEO Randall Stephenson, left, and Time Warner Chairman and CEO Jeffrey Bewkes are sworn in on Capitol Hill on Dec. 7, 2016, prior to testifying before a Senate Judiciary subcommittee hearing on the proposed merger between AT&T and Time Warner. (AP Photo/Evan Vucci)

Continuing, DOJ laid out some ominous possibilities as to how AT&T + Time Warner could harm rivals in both the tech and entertainment spheres:

The combined company would use its control over Time Warner’s valuable and highly popular networks to hinder its rivals by forcing them to pay hundreds of millions of dollars more per year for the right to distribute those networks. The combined company would also use its increased power to slow the industry’s transition to new and exciting video distribution models that provide greater choice for consumers, resulting in fewer innovative offerings and higher bills for American families.

Indeed, DOJ slyly quoted AT&T itself as saying that distributors with control over popular programming would “have the incentive and ability to use . . . that control as a weapon to hinder competition.” That is, AT&T could possibly use its “pipes”—its cable and cellphone services—to favor Time-Warner content, including, of course, CNN.

As Cuban suggested, AT&T’s defense will likely be two-fold:

First, all the tech companies play favorites to some extent, and the government has been fine with such favoritism in the past—so why come down, now, on AT&T? After all, every last thing that the consumer sees on Google, Facebook, Yahoo, and all the rest of them, is a choice by those tech companies. Yes, of course, each page view is determined by an algorithm, but so far, at least, the algorithms are controlled by people. So is it commercial bias? Or even, maybe liberal bias? We can be sure that AT&T lawyers will strike a rich vein if they dig into how and why rival tech companies make their decisions.

Second, AT&T, based in Dallas, will argue that it needs to grow in order to counteract the power of the Tech Lords of Silicon Valley. Indeed, Silicon Valley companies dwarf AT&T. We can compare: AT&T has a market capitalization of about $214 billion, while Facebook’s market cap is $525 billion; meanwhile, the market cap of Alphabet (Google) is a whopping $725 billion. So according to the “size matters” reckoning, not only is AT&T a relative piker, but also it’s perfectly obvious where the real behemoths are to be found. So why not let AT&T grow so that it can compete?

In fact, in the court battle to come, many experts think that AT&T can mount a winning campaign. After all, DOJ doesn’t win all of its antitrust cases. Indeed, the only certainty is that a lot of lawyers in D.C. and New York are going to make a lot of money on this case.

And yet it also seems certain that in the course of the anti-trust marathon to come, important questions about the power of the Tech Lords will loom large in the public consciousness. Is the power of the Tech Lords good for the American economy? Is their power good for American democracy? All the Tech Lords and all their p.r. agents and lobbyists won’t be able to stop people from thinking about these important questions.

Indeed, there’s already significant political ferment. Earlier this month, the Republican Attorney General of Missouri, Josh Hawley, announced that he was opening an investigation of Google’s business practices. As he said, “I will not let Missouri consumers and businesses be exploited by industry giants.”

And as the geek-insider site Ars Technica explained:

The danger for Google, then, is two-fold. First, the next Republican president may be as hostile to Silicon Valley as Trump has been. Even more ominously, the next Republican president is likely to have a much deeper bench of experienced Republican antitrust lawyers who see strict regulation of Google as a legitimate conservative objective.

So yes, the once-blindingly bright outlook for the Tech Lords is starting to look a little cloudy. It’s also worth noting that Hawley is running for the U.S. Senate next year; so obviously he thinks that scrutinizing the Tech Lords is a winning political issue.

Finally, we can recalling that back in 2008, Hawley wrote an admiring book about our 26th president, Theodore Roosevelt, often remembered as The Great Trustbuster.

So will trustbusting history repeat itself? We’ll have to see. Yet in the meantime, we can savor the irony that the anti-Trump Mark Cuban has become an inadvertent ally of Trump, and of the Republicans, in their coming populist crusade.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.