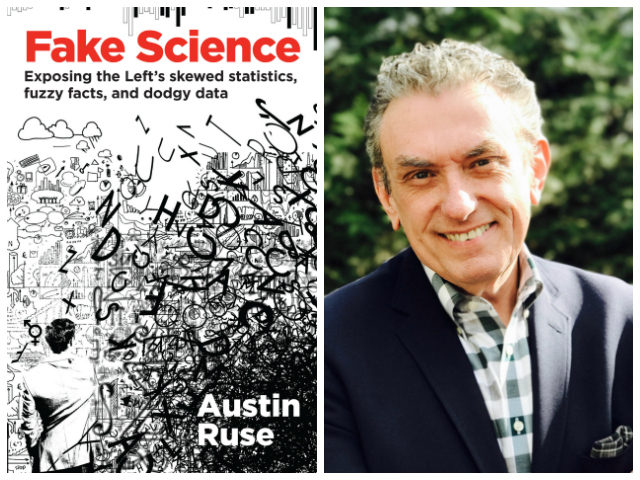

The following is an exclusive excerpt from Austin Ruse’s new book Fake Science: Exposing the Left’s Skewed Statistics, Fuzzy Facts, and Dodgy Data.

Surveying “Security” instead of Hunger

Starting in 1995, the USDA has conducted a regular survey of food security that measures food choices, intakes, shortages, and budgetary constraints. The 1995 report ties the lack of “food security” to lack of funds—an important fact to remember, in light of how the “food insecure” spend their money.

Between 1995 and 2006, the USDA defined four broad categories of food security: “food secure,” “food insecure without hunger,” “food insecure with moderate hunger,” and “food insecure with severe hunger.” In 2006, they changed their categories to persons with “low food security” and those with “very low food security.” They dropped “food insecurity with hunger” because not enough respondents reported that they felt hunger at any point during the reporting year. This ought to be a tip-off that something is fishy with government hunger numbers.

The USDA reports that the “eating patterns of one or more house- hold members were disrupted and their food intake reduced at least some time during the year because they couldn’t afford enough food.” Those households reported cutting back on intake—but also eating unbalanced meals or relying on cheaper food. Wait a minute. Is this really “hunger”? Who hasn’t had an unbalanced meal from time to time, or decided to go with the cheaper option on the menu?

Other stats from the survey do seem alarming at first. One in thirty adults in the United States is said to have experienced very low food security. One in thirty-five was hungry for at least one day because there was not enough money for food in the household. One adult in a hundred did not eat for a whole day because of a lack of money for food. But keep that “lack of money for food” in the back of your mind—more on it later.

According to the government, one child in 165 experienced very low food security. One child in 125 went hungry for at least one day because of a lack of money for food. One child in 250 skipped at least one meal because of a lack of food resources. One child in a thousand did not eat for an entire day because there was not enough money for food. Feeding America claims that thirteen million children are food insecure. But in fact the one-in-165 USDA statistic yields a total less than one tenth of that number. And the one child in a thousand who spent a whole day without eating equals about seventy-four thousand kids in the whole country. Even one hungry child is a tragedy. But the “anti-hunger” lobby is grossly exaggerating the scope of the problem—and proposing the wrong solutions.

It should be clear that though children are usually trotted out as at most risk of hunger, it is really adults who are most exposed to food insecurity. Only 4 percent of the food insecure are kids. About 7 percent are elderly, and a whopping 89 percent are non-elderly adults.

In congressional testimony in the summer of 2015, Heritage Foundation hunger and poverty expert Robert Rector said, “For Americans to go without food for an entire day represents a social problem, but it is a problem that is limited in scope, and it requires a well-informed policy response.”

How is it possible for Americans not to be able to feed themselves? Rector pointed out, “In fact, filling a stomach is quite cheap; 1,000 calories of rice, purchased in bulk, costs only 30 cents. In a pinch, an adult can fill his stomach and meet all his daily calorie needs with healthful but inexpensive foods for a dollar a day.”

The culprit is adults’ bad choices. “Cigarette smoking is a major cause of very low food security,” Rector told Congress. He is not a no-smoking scold; he is concerned about the cost of the habit. “Very low food security adults are much more likely to smoke than are food-secure adults, and money that is spent on cigarettes cannot be spent on food.”

According to Rector, “45% of adults with very low food security during the year smoked cigarettes during the 30 days before the survey.”

Using data from the National Health and Nutrition Evaluation Survey, Rector pointed out that 62 percent of adults “who reported they ‘did not eat’ for at least one whole day during the last 30 days before the survey because ‘there was not enough money for food,’ had smoked cigarettes during the month.” Lesson: stop smoking, eat, and feed your family. Rector figured that very low food security smokers consumed nineteen packs of cigarettes per month, at an average cost of $112 per month. That’s 63 percent of the cost of food for a single adult under the USDA’s “Thrifty Food Plan.”

Besides money wasted on cigarettes, there is the belief, particularly harmful to the poor, that fast food is a cheap way to eat. But fast food is not the poor man’s friend. Nothing could be further from the truth. A regular diet of fast food not only makes you fat and can kill you, but it’s also far more expensive per calorie than cooking and eating at home.

Rector pointed out that “a nutritious meal of rice and beans cooked at home provides around 2,200 calories for each dollar of food spending; by contrast, a Big Mac provides 138 calories for each dollar spent, as well as a lot of unhealthy fat.” Traditional food stuffs are far cheaper per calorie than fast food. All-purpose flour provides 4,717 calories per dollar; rice provides 3,599; rice and beans, 2,178; peanut butter, 1,750.

Sadly, low food security households spend 25 percent of their food budget at fast food restaurants or at vending machines.

And then there are the sugary soft drinks that make you fat and also cost a lot. Very low food security adults drink an average of two sodas per day. Presumably they buy them at $1.00 or $1.25 per can out of vending machines. This can run north of $70 per month.

Eliminating smokes and Cokes would put almost $200 more in the family food budget every month—just from cutting one person’s wasteful habits. Double that for a couple.

“Food insecurity” is a question of money. Folks spend unwisely, run out of money by the end of the month, and end up skipping a meal, eating less, or being worried about food. The vast majority of food insecurity— even very high food insecurity—could be alleviated by simple changes in behavior.

But the answer the massive food lobby favors is quite different: more and more money. They lobby for ever-more government spending, and they work feverishly to convince Americans to kick in yet more private donations as well. Lobbying and fundraising is where they spend a sizable chunk of their vast fortune. They also spend some of their lucre on food pantries and food banks, of which there are something like thirty thousand in this country. Rector, though, calculates that only a third of “very low food secure” families avail themselves of food banks or pantries. Two-thirds say they don’t have access to them.

And the “anti-hunger” lobby is only one part of the vast complex of “charitable” professionals and federal bureaucrats making a comfortable living off poverty in America.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.