NEW YORK CITY, New York — Bloomberg BusinessWeek National Correspondent Josh Green detailed in a Breitbart News Daily radio special on Wednesday his new number one bestselling book, Devil’s Bargain: Steve Bannon, Donald Trump, and the Storming of the Presidency, how Stephen K. Bannon met Andrew Breitbart, helped lift Donald Trump into the White House, and ripped apart Hillary Clinton. Green joined the program on SiriusXM 125 the Patriot Channel for a 45-minute special.

Bannon, now 63 years old, has had one of the most unlikely paths to being the White House chief strategist. He was the executive chairman of Breitbart News before President Donald Trump hired him last August to serve as CEO of the president’s successful campaign. But before all of that, Bannon had one of the most interesting paths to Washington of anyone in American politics, stretching from humble blue collar beginnings in Virginia to Virginia Tech to the U.S. Navy to the Pentagon up to Harvard Business School down to Wall Street out to Hollywood over to Hong Kong and back to the United States, before eventually rising as a cultural warrior alongside Andrew Breitbart in American politics and culture.

For Green, a lot of this has roots with former Alaska Gov. Sarah Palin—the 2008 GOP vice presidential nominee.

“The best way to tell the story is to come at it from the way that I did in the book and the story begins for me when I first met Bannon in 2011,” Green said. “At the time, I was a political reporter for the Atlantic Monthly, and I had just come back from Alaska doing a profile on Sarah Palin’s term as governor there because everybody—we in the media, I think Bannon himself too, thought Palin might run for president in 2012. And my piece on Palin was fairly contrarian, especially for me in the mainstream media, and I argued that if you look at her actual record as governor, she did pretty well. She fixed the state economy, she brought the oil companies to heel, and she really governed as a maverick during her two years she was in the governorship, and had some impulses that I thought were interesting ones; they were populist, maverick impulses.”

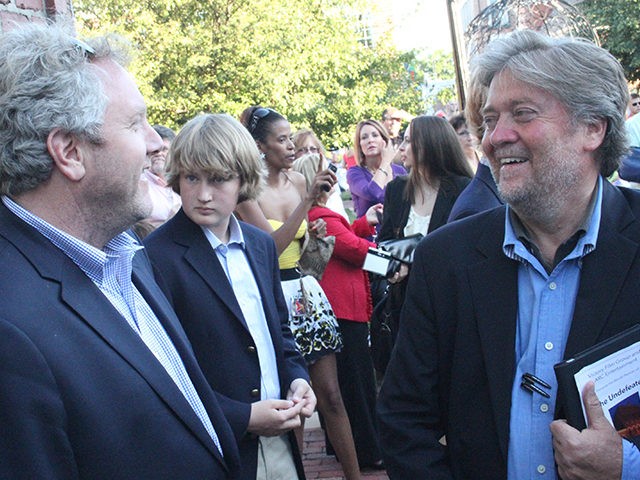

Bannon had just put together a documentary film on Palin, The Undefeated, something Green did not know when he was doing his Palin profile. It was at a screening of that film that Green met Bannon for the first time.

“I get back to D.C., and I get a phone call from a film publicist who says, ‘Hey, I represent this filmmaker who’s doing a documentary on Sarah Palin. Read your article and loved it. Can you come to Arlington, Virginia, to a sound studio tomorrow and see a screening of the film?’ I thought, ‘Sure,’” Green said. “I show up, and it’s Steve Bannon in all his ragged glory—the military field jacket and kind of exuding that manic charisma. We saw the Palin film, which I got to admit I was never a huge fan of, but Bannon himself was this fascinating character who had a very clear, distinct, right-leaning populist politics that you didn’t hear about in Washington a lot of the time. You live in D.C. I live D.C. Political people tend to be very doctrinaire, whether it’s the left or the right.”

Green and I discussed how most people in Washington are “cookie-cutter” types who fit into specific molds politically and intellectually, with rarely any people in national politics emerging as truly independent thinkers.

“Bannon was this kind of figure who was very different,” Green said. “He was just a fun guy to be around. My trade is long-form magazine-writing and what I try to do is collect interesting characters. We agreed to stay in touch, and over the course of the next few years, I hung out with him at political events. We’d go talk, and we followed some of the Breitbart stuff. I kind of got conscripted a little bit into the Breitbart universe, and then I learned about Bannon’s background. He’d been in the Navy. He’d jumped over to the go-go Wall Street in the 80s and worked at Goldman Sachs and had been in Hollywood, but what had really interested me about Bannon and what led to the big cover story I did about Bannon in BusinessWeek in 2015 was this elaborate plot that he had conceived with Peter Schweizer, with Breitbart, to take down Hillary Clinton—who we all knew, even back then, was going to be the Democratic nominee. Bannon’s analysis of where she was vulnerable and how conservatives could take advantage of that, I thought was really true because I covered Clinton’s campaign very deeply in 2007 and 2008, so I felt like I had a good feel for Clinton’s vulnerabilities and honing in on the financial relationships, the buck-raking, the speeches to Wall Street, that sort of thing. I had always thought that is where she was most vulnerable. Steve and Peter Schweizer had figured that out, too, and I thought had warranted a profile.”

In the book, Green noted that the first time he met Bannon, he sort of thought of Bannon as a typical political “grifter”—someone who swoops in to try to cash in on the latest fad in the country. But that changed as he dug deeper and learned Bannon was not pulling his chain and was, in fact, what he said he was.

“When I first met Bannon in this movie studio, I never heard of this guy, and I walk in, and he’s this wild character, and we’re talking after the movie, and he’s like, ‘Oh, yeah, I used to be an investment banker at Goldman Sachs. I was a Hollywood producer. I produced Sean Penn’s directorial debut. I just got back from Hong Kong running a video game company,’” Green said. “I mean, there’s a distinct Washington character type of the kind of people—I call them grifters, but who glom onto whatever the hottest thing is, whether it’s the Tea Party or Trump or whatever, but they’re really in it trying to make a quick buck. So initially, I sized Bannon up this kind of serial exaggerator or whatever, but I liked him. But later on, initially just for the hell of it—I’m a financial reporter, right?—I called a source at Goldman Sachs and checked: ‘Did a guy named Steve Bannon ever work there?’ And he goes and looks, and he goes, ‘Yep, he was an investment banker here in the 80s.’ And I did an IMDB search, and sure enough, there’s Bannon as executive director of The Indian Runner, Sean Penn’s [film]. The punchline is his story checks out. That often doesn’t happen, especially with political mover-and-shaker types. Like I said, once it was clear he was legit, I was kind of drawn to him because he had interesting and different ideas, but the thing about the facts—the thing I thought was so shrewd about his analysis—was Bannon was very politically self-aware of where conservatives had erred in the past.”

So Bannon set out over the past several years to use his vast resources and institutional knowledge from his long history to correct the pathway forward for conservatives heading into the 2016 presidential election.

“He had an interesting critique of why Republicans had failed to stop Bill Clinton in the 1990s even though they impeached him,” Green continued. “Bannon’s line was the problem was conservatives were trapped in their own bubble, trapped in their own ecosystem, talking to themselves in an echo chamber, and they didn’t realize that the mainstream media, Democrats and independents, didn’t believe them and weren’t listening. So even though they impeached Bill Clinton, he winded up doing just fine, and Democrats won seats in Congress. Bannon’s contention was that was because conservatives at the time had chased these kinds of wild rumors and blown their credibility, so the way to stop Clinton this time was to build a rigorous case built on facts that documented all of these allegedly nefarious relationships and put them in a book that wasn’t full of opinion and hyperbole and rumor and exaggeration and then take that material and hand it off to investigative reporters at mainstream newspapers like the New York Times, like the Washington Post, like Bloomberg News, on the belief that reporters—while many of them themselves may be politically liberal, they care enough about stories and investigations that they’ll take this material, they’ll check it out, and if it’s real, they’ll run stories about it and spread this message through the mainstream media in a way that conservatives were never able to do in the 1990s. In any event, that’s exactly what happened. The first big story based on Clinton Cash reporting was above the fold front page New York Times; it completely changed the contours of American politics.”

All of this, of course, was possible because Bannon met Andrew Breitbart in 2004 at the screening of another one of his documentaries, In the Face of Evil.

“One thing to know about Bannon is he is a very serious student of film history,” Green said. “He, like a lot of people in Hollywood, he came into the industry from the money side but his real passion was to move over to the creative side. He studied films, especially studied the Soviet and German propagandists of the 30s and 40s. Bannon loved that stuff. If you look at the opening scene of the In the Face of Evil, it’s an homage to one of those 1940s films. He’s very interested in the idea of using film as a medium of persuasion to kind of awaken and enlighten the masses in the same way that filmmakers did in the 1930s and the 1940s—and you can see that pretty clearly in In the Face of Evil. So Bannon took his own money, optioned the rights to Peter Schweizer’s book Reagan War, which is what it was based on, and made this documentary. I believe it was the debut. They debuted it at a conservative festival in Hollywood where Andrew Breitbart—who was working for Drudge at the time—he’s sitting in the audience. And after the film—I tell the story in the book—Bannon says, ‘This big bear of a man comes bounding out of the audience and like wraps his arms around me and says, “Brother, we got to change the culture. You’re one of us.”’ And as so many people did, Bannon, I really think, became enamored with Andrew Breitbart—both as a person and a political force, but especially, I think, for Bannon, as someone who understood at a visceral level how to shape media narratives. Andrew, because he had worked for Matt Drudge, had been inside the control room of the machine of the Drudge Report, and Bannon was fascinated by Drudge’s ability to essentially set the cable news dialogue, what stories wound up on the front page of major newspapers, by billboarding them on the Drudge Report and directing masses of his readers to these stories.”

Green noted that ever since Drudge broke the Monica Lewinsky story in 1998, “every producer, reporter, editor—they click on Drudge Report ten times a day. It’s always there. If Drudge is following a story and blowing it up big, we go follow it. I think Bannon wanted to learn that tradecraft and talked about it in a way that it was almost like being indoctrinated into a medieval guild. You were learning these skills he thought he could bring to Breitbart News.”

One place Bannon and Breitbart really personally connected, too, Green notes, is on the understanding both had of the dire circumstances Western civilization itself is in and just how important these fights are. Breitbart News’s motto as a news organization, of course, is #WAR.

“When I did this big profile, I interviewed Steve and another guy with a Drudge background, Alex Marlow—editor-in-chief of Breitbart. I know both those guys a little bit, had known them at the time; this is two years ago back in 2015,” Green said. “And, there’s a lot of criticism—to the extent the mainstream media paid attention to Breitbart back then, it tended to be for the over-the-top headlines, the stuff people found outrageous or offensive, whether it was about race or crime or immigration or gay marriage or marijuana legalization. I remember sitting in the interview saying to these guys, ‘You both seem like really educated, cosmopolitan people. Do you really have a problem with gay marriage? It doesn’t seem to me like you would.’ I thought the answer was really interesting, and I can’t remember if it was Alex or Steve, but they said, ‘Look, we’re fine with a lot of this stuff. What we don’t like, though, is the fact that every time one of these traditional values falls, liberals in the media go out and do this kind of grave dance to celebrate the destruction of tradition and identity and that sort of thing.’ That was kind of my first clue that this wasn’t just about arguing over politics and presidential candidates or bills in the House on the Hill. It was really something different: about culture. Not to geek out too deep, but one of the things I go into in the book is kind of the intellectual and religious lineage of Bannon’s nationalism—which is really steeped in his traditional Catholic upbringing and led him to a lot of nationalist philosophers.”

LISTEN TO JOSH GREEN ON BREITBART NEWS DAILY ON SIRIUSXM 125 THE PATRIOT CHANNEL

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.