Thursday’s nuclear option vote restores 200 years of Senate practice, going far beyond Neil Gorsuch’s confirmation to restore the proper constitutional balance for Supreme Court and federal court appointments.

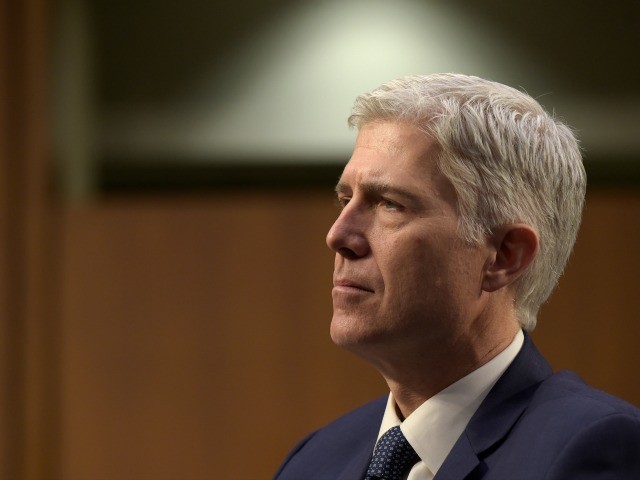

On April 6, the U.S. Senate voted 52-48 to extend Senate Democrats’ own precedent to guarantee that Supreme Court nominees can be confirmed with a simple-majority vote of 51 out of 100 senators. As an immediate result, Gorsuch was confirmed as a Supreme Court justice Friday morning by a bipartisan vote of 54-45, but the benefits to the Republic will last for decades.

Article II of the Constitution vests the power to appoint judges jointly between the president and the Senate. From the ratification of the Constitution in 1789 until 1987 (same digits, but in a different order), judicial nominations followed a particular pattern. The president takes the lead by nominating anyone he wants. Then the Senate either approves or disapproves of that choice by an up-or-down confirmation vote.

Their roles were always different. The president would consider every aspect of a nominee, including whether the nominee reflected the president’s philosophy on how to understand the Constitution, the law, and the role of the courts in America’s democratic republic.

The Senate’s role was more limited. The Senate does not pick the nominee; instead it was a check on the president so that, as Alexander Hamilton explained in The Federalist Papers No. 76:

To what purpose then require the co-operation of the Senate? I answer, that the necessity of their concurrence would have a powerful, though, in general, a silent operation. It would be an excellent check upon a spirit of favoritism in the President, and would tend greatly to prevent the appointment of unfit characters from State prejudice, from family connection, from personal attachment, or from a view to popularity. In addition to this, it would be an efficacious source of stability in the administration.

In other words, the Senate would ensure that the president did not choose someone on an improper basis, such as because that person was a family member, or a good friend, or perhaps the president owed the nominee money.

In practical terms, that means the Senate traditionally looked to three objective criteria to determine if a nominee was fit for office: education, experience, and character. So long as a judicial nominee satisfied those requirements, the Senate would respect the president’s prerogative. That was why Justice Antonin Scalia—whose seat Gorsuch will now fill—was confirmed in 1986 by a vote of 98-0, despite his crystal-clear record of being very conservative.

But then the very next year, something unprecedented happened when President Ronald Reagan nominated Judge Robert Bork, who might have been even more qualified for the Supreme Court than Scalia or Gorsuch, as extremely qualified as those two men were. (Bork was a former U.S. solicitor general, Yale law professor, one of the greatest legal scholars in all of American history, and a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit.)

Democrats took control of the Senate in the 1986 midterm elections, and it had become an article of faith in that party to protect sacred cows leftists were getting from a liberal Supreme Court that they could not get through the ballot box, like abortion on demand, racial preferences, and militant secularism.

In 1985, Attorney General Ed Meese declared that the official constitutional philosophy of the Reagan administration was originalism: In our democratic republic, the only legitimate way for unelected, politically unaccountable judges to interpret the law (and especially the Constitution as the Supreme Law of the Land) was according to the original meaning of its provisions, leaving it to the American people alone to decide whether the Constitution or lesser laws need to be changed or amended.

Reagan and Meese made good on that philosophy when Reagan elevated Scalia to the Supreme Court. With Bork—who was even more conservative than Scalia—nominated to the Court, the Left saw the possibility of an eventual Supreme Court majority that would destroy their decades-long march to achieve their agenda without earning the votes of the American people.

Consequently, Sen. Ted Kennedy (D-MA) led the charge to destroy the unbelievably well-qualified Bork, purely because Bork was an unapologetic conservative who openly explained his judicial philosophy. The Democrat-controlled Senate voted down Bork’s nomination. That seat on the Court eventually went to Anthony Kennedy.

Several years later it almost happened again. Justice Clarence Thomas was narrowly confirmed, 52-48.

Republicans tried to restore the constitutional balance. Ruth Bader Ginsburg was confirmed 96-3 in 1993, despite being as clearly very liberal as Scalia, Bork, and Thomas were clearly conservative. In 1994, Stephen Breyer was confirmed 87-9.

But Democrats would have none of it. When the very well-qualified Samuel Alito was nominated, he was confirmed in 2006 by a vote of 58-42. To avoid a double-standard, this new baseline started to impact how Republicans voted on Democratic nominees, as seen in the confirmation votes of Sonia Sotomayor (68-31) and Elena Kagan (63-37).

But the Left did not stop at the Supreme Court during these years. When George W. Bush was elected president, Senate Democrats in 2001 narrowly controlled the Senate 51-49, and began refusing final floor votes on Bush’s nominees to the federal courts of appeals. As an example, they refused to vote on the nomination of John Roberts to be a judge on the D.C. Circuit appeals court.

The American people did not tolerate this, and gave Republicans control of the Senate in the 2002 midterms.

Now in the minority, Democrats decided to double-down. One first-term senator, Chuck Schumer (D-NY), persuaded most of his colleagues to begin filibustering nominees they did not support, even when some Democrats were willing to join with the Republican majority to confirm them. Roberts got through to the D.C. Circuit anyway, but others—like Miguel Estrada, another nominee to the D.C. Circuit—were blocked.

As Republicans continued to gain seats in the Senate, Democrats considered taking things to still another low. They decided against filibustering Roberts’s nomination to the Supreme Court, but tried to do so on Alito. But that was a bridge too far for many Democrats at the time, which is why cloture was invoked on Alito 72-25, even though many of those Democrats who voted for cloture then voted against his final confirmation on the up-or-down vote, resulting in 58-42.

Finally with Gorsuch, Schumer led Democrats to claim the role of co-appointers of federal judges, merging filibusters with final confirmation votes. If a Republican president nominated someone whom Democrats would not have nominated (which presumably would be the case 100 percent of the time), Senate Democrats would not only vote against final confirmation, but also vote against cloture, regardless of qualifications.

Under the historical standard, President Donald Trump’s nomination of Gorsuch is a slam-dunk. Education? Undergraduate degree from Columbia, law degree from Harvard, and even a doctorate from Oxford. Experience? Law clerk for the U.S. court of appeals and for the Supreme Court, then a partner at a prestigious law firm, also U.S. deputy associate attorney general, then finally a federal judge for more than ten years on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit. Character? Impeccable honesty and integrity, as well as being a good husband, father, and member of his community, and known to be a gracious, humble, and respectful gentleman.

Because it takes 60 votes to invoke cloture, for the first time in American history putting cloture and final passage on the same level created a 60-vote threshold for confirmations, meaning that without 60 votes for both, a nominee would be filibustered. Unless Republicans would consistently hold a 60-vote supermajority on the Senate, it became possible that a vacant Supreme Court seat could conceivably remain unfilled for a full presidential term.

Critics insist that Schumer’s hypocrisy here was shameless, because during the Obama years, when Democrats narrowly held the Senate, for a while Republicans followed the Democrats’ new standard, and filibustered a couple of President Barack Obama’s nominees.

Crying self-righteous indignation, in 2013 Sen. Harry Reid (D-NV), Dick Durbin (D-IL), Pat Leahy (D-VT), and Schumer created a parliamentary ruling that the filibuster rule, Senate Rule XXII, did not apply to any presidential nominees, except that the ruling did not explicitly cover the Supreme Court. During this time, Schumer gave a passionate speech about how preventing an up-or-down vote on judicial nominees was profoundly undemocratic, and an assault on the constitutional order.

So Democrats created that precedent on November 21, 2013, one that did not address the Supreme Court simply because there was no Supreme Court vacancy at the time. During the 2016 campaign, Hillary Clinton’s running mate and Senate Democrats publicly declared that when they won the White House they would immediately extend their ruling to cover the Supreme Court.

Consequently, jaws dropped when Schumer declared with righteous indignation that denying a minority the right to filibuster by insisting on an up-or-down vote was profoundly undemocratic, and an assault on the constitutional order. This was the same time that Senate Democrats made clear that virtually every senator who opposed Gorsuch’s confirmation would also oppose cloture, solidifying a 60-vote threshold for judicial nominees from Republican presidents.

This ultimate double-standard and the warping of the constitutional framework was the last draw, which is why on Thursday Republicans ended the madness. They highlighted the fact that this was purely a response to what the Democrats had done, by phrasing the procedural issue as whether “the precedent of November 21, 2013,” applied to Supreme Court nominations. By a vote of 52-48, senators issued a “judgment of the Senate” that the Democrats’ own rule applies here, abolishing the remaining judicial filibusters.

Now the Republic goes back to where it stood for roughly 200 years. Elections have consequences. When the American people give the presidency and the Senate to opposing parties, they have the choice of picking comprise candidates (if there is such a thing these days) or of keeping seats open. When the American people speak with one voice to give the same party control of both the White House and the Senate, then it should be no surprise that they are able to get judges who reflect that unified philosophy on the federal judiciary at every level—including the Supreme Court.

Ken Klukowski is senior legal editor for Breitbart News. Follow him on Twitter @kenklukowski.