Third of Three Parts

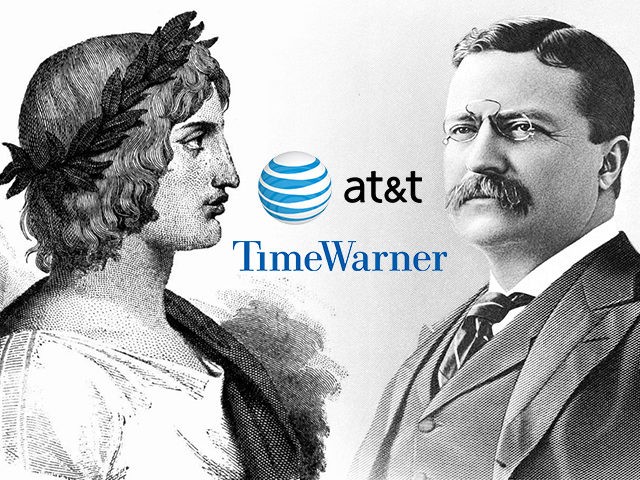

Theodore Roosevelt Explains His Theory of Antitrust: Why Size Doesn’t Always Matter

by Virgil, with Theodore Roosevelt

In Part One, we considered the curious partisan political inversion around the proposed AT&T-Time Warner deal, as Donald Trump has come out noisily in opposition, while Hillary Clinton seems quietly supportive.

In Part Two, we introduced our guest-expert, the Great Trustbuster himself, Theodore Roosevelt, who explained that the history of the Republican Party’s antitrust policy is more complex than most people realize.

Now, in Part Three, we will press Roosevelt for a specific opinion on the AT&T-Time Warner deal, and he will expand on his quantity-vs.-quality theory of regulation.

Virgil: Theodore, you have the floor.

Theodore Roosevelt: Because everyone’s busy, I will summarize the arguments I made about antitrust in my 1901 speech. I said that rather than go off half-cocked, we should study the situation, gain a maximum understanding of business dealings, and then and only then formulate a plan. To use a nautical analogy, the wise ship-captain must have good charts before he lifts anchor.

V: Indeed, you published a book of sea-going military history, The Naval War of 1812, when you were 23 years old—and it’s still in print today. Impressive!

TR: Thank you. My understanding of naval history helped me a lot when I was Assistant Secretary of the Navy—

V: —back when there was a grand total of one Assistant Secretary of the Navy.

TR: Right. As Sir Francis Bacon said at the dawn of the Scientific Revolution in the 17th century, knowledge is power. And that’s true for any situation.

And so in regard to the AT&T-Time Warner deal, before offering a judgement, I’d like to have more knowledge. For instance, I’d like to know more about this October 25 story in The Daily Beast, “AT&T Is Spying on Americans for Profit, New Documents Reveal.” I don’t wish to prejudge the truth, and I learned a long time ago not to trust everything I read in the newspaper, er, news media. In addition, I’m no foe of internal security, so if I were still a policymaker, I would seek out all the relevant and appropriate facts.

V: And so after you gather the data . . .

TR: Then we need a good plan. Sometimes, of course, doing nothing is a good plan. But most of the time, a good plan is an active plan. A strenuous plan, some might say.

And as to plans and new things, back in ’01, I called for the creation of a department of commerce for my cabinet. And in ’03, I was pleased to sign legislation creating the Department of Commerce and Labor.

V: A Department of Commerce and Labor?

TR: Yes, after my idea went into the Congressional sausage factory, it ended up becoming the Department of Commerce and Labor, which I thought was well and good. That double-arrangement lasted until 1913, when “labor” was carved out and a separate Department of Labor was established.

I’ll admit, back then, in my retirement, I wasn’t entirely happy about that splitting off, because I have always believed, per Henry Carey, that business and labor should work together; I regret that business and labor are often put into separate, and antagonistic, silos.

V: Forgive me, sir, but creating a cabinet department called “Commerce” doesn’t quite seem to be an answer to the challenge posed by populism. The US still has that Department of Commerce, and it doesn’t seem to do very much.

TR: Quite true. But my idea was different: I wanted my Department of Commerce to have genuine regulatory teeth.

V: Interesting . . .

TR: You see, business regulation can come in two main forms. We might think of it as the distinction between quantity and quality.

As to quantity, which is to say, size, the government can choose to focus on the largeness of a business—that’s what antitrust is all about.

I should add that, to my mind, all talk of “competition” in antitrust enforcement is mostly just a cover for a more elemental instinct that people often have—namely, that a given business is just too darn big. And if people think a business is too big, they can always conjure up a highfalutin rationale for cutting it down to size. I can understand that anti-big sentiment, but I don’t often agree with it.

V: Okay, that’s one kind of regulation, quantity. What’s the other kind of regulation?

TR: The second kind of regulation is about quality—the actual nature of the thing itself. How does it behave? How does it treat its workers? How does it treat its customers? Does it operate in the public interest? If you think about it, those sorts of qualitative questions exist independently from the question of size, or quantity.

V: You mean, a big company can be good, and a small company can be bad.

TR: Exactly. We want all companies to be good, and if they are good, there should be no objection to seeing them grow. It’s perfectly right and proper to reward corporate virtue with growth and profitability.

I might add that this second kind of regulation, about quality, is more often called supervisorial. In that same 1901 speech, I used the word “supervision,” or a variation of it, a total of seven times. That is, the government, preferably the federal government, must lay out the rules of the road; it must supervise.

V: Why the federal government, as opposed to local and state government?

TR: Look, I’m no detractor of local and state government. I was proud to serve as police commissioner of New York City, and then I was proud to serve as governor of New York State.

And yet as corporations grew, just in my lifetime, to almost unimaginable size, it became obvious that big firms, operating in all the 45 states—oops, I mean 50, we were at 45 when I came into office, and in my time, we added Oklahoma, with, of course, four more states coming later—could make a mockery of state-by-state regulation.

So again, we need a national government, a government that exerts national leadership, including in the regulatory realm.

V: So “supervision” is really national supervision?

TR: Yes. A key part of the social contract is that everyone does his or her part. That’s good citizenship, especially if it’s a corporate citizen, enjoying the considerable legal benefits of incorporation. As I said in 1901:

Great corporations exist only because they are created and safeguarded by our institutions; and it is therefore our right and our duty to see that they work in harmony with these institutions.

V: There’s that word again, harmony.

TR: Yes, and obviously, as part of the promotion of harmony, the privileged and powerful have an extra burden—to lead by setting a good example. Which seems only fair.

Yet regardless of size or standing, rules are rules, and everyone should abide by them.

V: Wherever their social station.

TR: Yes, indeed. But again, those at the top have extra responsibility.

To begin with, profitable businesses should pay their fair share of taxes. In addition, they must follow the rules of fair play and the rules about conservation and pollution. And of course, these days they must also obey a thousand other laws and regulations, concerning occupational safety, discrimination, sexual harassment, and on and on.

V: Red tape.

TR: Yes. It can be a curse. In fact, I think we have too much red tape for business—and especially too much of what’s now called “political correctness,” mandated by the bureaucrats and the courts.

And yet here’s something that’s strange to me, Square Dealer that I am. We regulate word-choices in the workplace to the most elaborate degree, and yet we don’t pay much attention to the basics of industrial justice—that is, how much workers get paid, how to protect them from unfair competition by illegal aliens, and how to thwart layoffs, offshoring, and other forms of unfair profiteering. To put the matter in the bluntest terms, we regulate the little stuff that doesn’t much matter, but we ignore the big stuff that really does matter.

V: Of course, I realize that to a trial lawyer, or to a judge, or to a bureaucrat, the little stuff can make for a lucrative career.

TR: Yes, I’m afraid you’re right. And in such a costly environment, capital often finds it easier to do its building and hiring overseas. Instead, we want America to be the hub of hiring and building.

V: That’s a very Republican-sounding sentiment.

TR: Yes, by God, I am a Republican! I believe in free enterprise, private property, and freedom in general! I know that many of my enemies have regarded me as some sort of leftist, but I’ve always embraced the same consistent conservative wisdom about liberty and property.

And yet, per Burke, Disraeli, and other rightist sages, I’ve also always believed that the wise leader must see when it’s necessary to change, and then be willing to make that needed change. Otherwise, we risk rack, revolution, and ruin.

V: So let’s step back—back to regulation. You’re saying that the size, or quantity, of a company matters less than the nature, or quality, of that company. The quality that is, of its willingness, and ability, to comply with the rules.

TR: Yes. In the modern age, we must accept that companies will grow big, and yet we always want them to behave themselves.

Indeed, it’s entirely appropriate for companies to grow large, because this is a large country. Moreover, we are competing against other big countries with their own big companies. The common phrase these days, used around the world although not so much here, is “national champions.” I like that concept. I think we need more national champions, companies that can go toe-to-toe with other nations’ champions in the international economic arena.

You see, this is a world that is increasingly guided by Asian ideas of corporate consolidation and dominance—that is, the guiding vision of Japanese zaibatsu and Korean chaebol, two important words for industrial hyper-powers. I think we, too, need some of those “incredible hulks” on our side. Just as you fight fire with fire, so, too, you fight size with size. Yet at the same time, of course, our national champions have to play by the rules.

V: That’s a lot of concentration. And a lot of bigness.

TR: Now, Virgil, I know that you wrote the Eclogues, as a tribute to the simplicity of rural life—

V: Hey now . . .

TR: —but the fact remains that only bigness guarantees survival. That is, one must be large enough to fight for oneself. For instance, you Romans were never going to beat the Parthians, or the Teutons, with bucolic decentralization. Instead, you needed the mighty military that only centralization could guarantee.

Virgil: Ah, and yet there’s much to be said for the simple life. As I wrote:

The trees are cloth’d with leaves, the fields with grass;

The blossoms blow; the birds on bushes sing;

And Nature has accomplish’d all the spring.

TR: That’s really very nice, and nobody enjoys the great outdoors more than I. And yet the tournament of nations is won by strong militaries backed up by strong economies with strong industries. When I sent the Great White Fleet around the world in 1907, that was possible only because we had the muscle and might of America—including corporate America—in our corner.

So, in other words, you can’t turn back the clock. There can be no return to some idealized edenic world. We must recognize that times change, and we must accept the vigorous challenge of living in the present day, amidst all its dangers.

V: Your words are painful to my poetic soul . . .

TR: Remember, Virgil, after you wrote the Eclogues, you then wrote the Aeneid, which is, of course, one very long ode to imperial power.

V: True.

TR: So we agree: When times change, needs change. As I said in that same 1901 speech:

When the Constitution was adopted, at the end of the eighteenth century, no human wisdom could foretell the sweeping changes, alike in industrial and political conditions, which were to take place by the beginning of the twentieth century.

V: But what about freedom and liberty?

TR: My dear boy, I am describing how you preserve freedom and liberty! The Bolshevik Revolution in Russia came after my time in the White House, but even at the turn of the century, revolution was in the air; as I’ve noted, it was radicalism that killed poor President McKinley. So yes, we must always be willing and able to suppress violence, but we must also be willing and able to address the injustices that provoke ill-will and violence.

Thus as paradoxical as it may seem, sometimes one needs regulation in order to enjoy freedom. After all, it’s only when everyone plays by rules that are fair-and-square that the individual can enjoy life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. As my friend Herbert Croly explained, if we wish to achieve Jeffersonian goals, then we must apply Hamiltonian mechanisms.

I might add, too, that it’s simply not sufficient to leave these matters to the “invisible hand,” hoping that things will just work out. As I saw in my time, and as Americans have been reminded in recent years, the invisible hand often turns out to be nothing more than “the thudding fist of the powerful.” Yet let me emphasize: That’s not an argument for socialism; it’s an argument for enlightened capitalism.

V: In other words, within an ordered structure, one finds freedom and autonomy. Indeed, that’s what we Romans thought.

TR: Yes. The Roman emperors, including your man, Augustus Caesar, weren’t quite my cup of tea, but the earlier Roman Republic—now that was a great institution!—was a model, of course, for our own American Constitution.

And if we’re on the subject of order and structure, as I’ve said, I’m always more interested in the quality of a structure, as opposed to its quantitative size. A bad actor can be small, or he can be big—it’s not the size that matters, it’s the character.

So that’s why I thought we needed national regulation to deal with national problems—so that all companies, small as well as big, would have to adhere to a certain set of standards. In particular, my idea, back then, was to build upon the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887, which had begun—but only barely begun—the necessary process of regulating the railroads.

Yet early on in my presidency, I found that I didn’t have much in the way of legal tools. And so I had to rely on my own personality, plus, of course, the presidential “bully pulpit.”

For example, in 1902, I confronted a coal strike that threatened the entire national economy. The miners, of course, wanted a big raise, while the mine operators, of course, were offering no raise at all. My solution was a compromise: a modest-sized raise, and an end to the strike. Nobody was completely happy, but the economy was nevertheless protected.

Once again, it’s all about the harmony of interests. In the end, miners want to work, and mine operators want their profits. So if the two sides can be made to see past their angry passions and recognize their own true self-interest, a bargain can be struck, and harmony can be restored.

Indeed, in my time as president, I even applied that conservative principle of stewardship to college football. In those days, when there were no helmets, hundreds of young athletes were being killed or crippled on the gridiron every year. Look, I adore sports, including football; I would’ve loved to have played at Harvard, were it not for my asthma. Yet at the same time, I could see that if the carnage on the playing fields were to continue, there wouldn’t be any college football. So I called in the schools and the coaches and mediated a solution, including such “reforms” as the forward pass and the abolition of mass formations. Thus I saved the game as a collegiate sport.

V: Speaking of harmonious mediation, you won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1906 for mediating an end to the Russo-Japanese War.

TR: Yes, so much for another myth about me, that I was some kind of warmonger!

Yet at the same time, mediation can only go so far—it’s not always applicable. That is, sometimes, a leader needs that iron fist inside the velvet glove. And thus we come back to regulation. As I’ve said, I don’t really care about the size of a man, or the size of company, so long as he, or it, plays by the rules. And it always helps when those rules are clear, enforceable—and enforced.

In the White House, I came to realize that the selling of dishonest and adulterated products was not only a scandal, but also a dire threat to public health. So in 1906 we passed the Food and Drug Act. In that instance, I wasn’t interested in mediating anything, because when the public is at risk, there aren’t two sides to the story; there’s only one side—the right side.

V: So there’s a time for mediation, and there’s a time for protection.

TR: Yes! Also in ’06, I could observe that even after the creation of the Interstate Commerce Commission in 1887, the railroads were still in gross violation of their public trust. Once again, mediation, by itself, was hopeless, because the railroads weren’t interested. Again, the only answer was regulation.

Yet many of my fellow Republicans, led by the execrable Sen. Aldrich, were not interested in doing anything about the railroads. Yes, the reactionaries of that era thought it was okay for a railroad to be built and maintained at public sufferance—and yet they also insisted that all the rights belonged to the railroads, and that the public had no meaningful rights.

V: What do you mean?

TR: Look, all those railroads were built only because of legal and political clearance. That is, rights-of-way had to be gained, often by eminent domain. In addition, many of the railroad lines were built with bonds either issued, or guaranteed, by the public. And then, of course, all that private property that was accumulated had to be protected by public authorities. So surely, after all that public subsidy and effort, the public interest, too, deserved consideration. And plenty of Republicans—out of the Lincoln-McKinley tradition—agreed with me. But as I said, plenty of other Republicans, the servants of capital, did not agree. Hence the political tussle.

Indeed, because so many of my fellow Republicans were stubborn about reform, I had to work with Democrats. In 1906, I ended up working with both parties in Congress to pass the Hepburn Act, which for the first time gave real muscle to the Interstate Commerce Commission. Congressman William Peters Hepburn of Iowa was a Republican, but my principal ally in the Senate, behind the scenes, was Sen. Benjamin Ryan Tillman, Democrat of South Carolina, known as “Pitchfork Ben.”

V: He sounds like a scary fellow.

TR: Tillman was very much an angry populist. Yet at the same time, he was a shrewd operator, who understood that his region, the South, was losing in the power struggle with the great railroads. And so we worked together, albeit indirectly. In fact, we ended up at odds in the final passage of that bill. And yet despite all the acrimony, there was never a moment when Tillman and I didn’t share the same ultimate belief—that is, in the need to regulate the railroads.

V: How Machiavellian of you!

TR: Yes, I suppose it was. You know, Machiavelli is misunderstood. He is regarded as some sort of conniver, when, in fact, he was an Italian patriot, centuries before Garibaldi and Italian nationalism. Machiavelli wanted to use his political skills to build a united Italy that couldn’t be conquered by enemies; yet today, he is remembered as just a clever sneak. Sad!

As for me, I believe that politics should always be about the commonweal, and yet at the same time, as Machiavelli certainly also understood, one can’t take the politics out of politics.

In fact, Tillman and I, different as we were, found common ground on another important issue, too. In the following year, 1907, I was pleased to sign the Tillman Act, which banned corporate contributions to politics. That law was in place, I might note, for more than a century, until it was overturned in 2010 by the Supreme Court in the Citizens United case. And now, in 2016, as Hillary Clinton and her donors are trying to buy this election, I might ask my fellow Republicans: Do you really think that the GOP is better off with unlimited donations? Are Republicans better off if Democrat George Soros, with his unlimited resources, can give unlimitedly to Democrats?

V: It looks to me as though many Republicans would rather have the continuation of big donations that go them, even if, in fact, the Democrats get more.

TR: Yes, I’m afraid that too many Republicans have gone over to the side of Aldrich—that is, making a kneejerk defense of concentrated corporate power, even if, politically speaking, that has proven to be a losing proposition.

Indeed, it seems sometimes that it’s hard to identify that Lincolnian strand—the idea that labor is prior to capital—in today’s GOP.

V: All right, speaking of “concentrated corporate power,” let’s talk now about the AT&T-Time Warner case.

TR: As I’ve said, I’m not hostile to “big,” in and of itself.

V: Yet I’ve learned that under your administration, the federal government filed a big antitrust case against the American Tobacco Company, as well as laying the groundwork for an even bigger antitrust case against Standard Oil. You are, after all, known as the Great Trust-buster.

TR: Yes, well. Those two cases you cite were egregious; Standard Oil was especially egregious: It had a 90 percent market share, and was no kind of good corporate citizen. So something had to be done, and I’m glad Will Taft did it.

V: Even though you had your differences with him.

TR: Yes, we met angrily on the political battlefield in 1912, although ultimately, we managed to put all that behind us.

And yet if we can return to antitrust and regulation: As I have said, I never felt, as president, that I had all the right regulatory tools needed to achieve industrial justice. If only the Department of Commerce had been enacted the way I originally intended, then that’s how I would have preferred to handle the question of corporate consolidations.

V: Yet at the same time, always, these entities, big or small, must be regulated.

TR: Yes. And now, as for AT&T and Time Warner, I am much more interested in understanding how the deal would serve the interests of the nation, rather than seeing how well these companies, or any company, will fit on some arbitrary Procrustean Bed, measuring only size, or quantity, and not quality. After all, corporations must serve the nation that spawned them. That is, indeed, the Roman ideal.

V: Yes. The cursus honorum, as we called it back in the day.

TR: Right! The idea that serving the nation is a sacred calling—that’s an idea that seems, unfortunately, to have been lost in recent decades.

And also lost, I might add, is the sturdy idea that conscious statecraft is needed to take care of our own and to advance the national interest. It seems that the avant-garde right, as well as the left, has gone in for a different idea—that we must be subservient to the world, and all its migrant peoples, and subservient also to the global market. I totally disagree.

Instead, the old-fashioned conservative in me recognizes that some things, such as national well-being and national honor, must always be conserved. And yet at the same time, the progressive in me recognizes that treasured verities must be actively conserved. If they are left on their own, unsheltered, they are too easily eroded, or even destroyed. Hence the Square Deal: Bringing the benefits of the American Dream to all requires a lot more than antitrust, because ill-fortune, and injustice, can come in all sizes.

V: Theodore, you’ve clarified a lot. Thank you very much for your time.

TR: You’re welcome. As you can see, I have plenty of time. Indeed, in my infinite free time, I have ample occasion to worry about the future of my country.

V: So you’re always on watch, even from these nether ramparts.

TR: Yes. I’ve been dead for 97 years, but I’m still around, still a presence in American life.

V: As you should be.

TR: You’re a good man, Virgil! So in closing, please let me read what I said in a speech to the Union League Club of Philadelphia in 1905. I think it lays out nicely my hopes for the country and its future:

We do not intend that this Republic shall ever fail as those republics of olden times failed, in which there finally came to be a government by classes, which resulted either in the poor plundering the rich or in the rich exploiting and in one form or another enslaving the poor; for either event means the destruction of free institutions and of individual liberty.

V: Well said, sir! Oh, and one last thing, Theodore, before you go: As was noted at the beginning, what can be done about CNN’s political bias? Do you think there’s anything that can address that?

TR: Ha! I’ve always seen myself as a problem-solver. But I think that particular problem is hopeless. No matter who, or what, owns it, CNN will aways be . . . CNN.

V: Thank you, Mr. President.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.