Mass immigration is pushing huge costs on to state taxpayers for schooling, crime and welfare, says a new report by the prestigious, government-endorsed National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine.

Each immigrant costs state and local taxpayers roughly $1,600 more per year than the immigrant generates in taxes, the report notes. In total, the current annual net cost of first-generation immigrants — including the cost of educating their children — adds up to $57.4 billion per year, much of which is paid by state and local taxpayers.

The per-immigrant cost is roughly equal to tax surplus paid by one native-born American, which ranges from $1,300 to $1,700, says the report, titled “The Economic and Fiscal Consequences of Immigration.”

So each first-generation immigrant consumes all the leftover taxes from one native-born worker, after receiving various benefits from the state, according to the report.

Federal taxpayers also lose out on immigrants, mostly because relatively few immigrants get the college degrees needed to earn enough money to pay more in taxes than they receive in federal benefits.

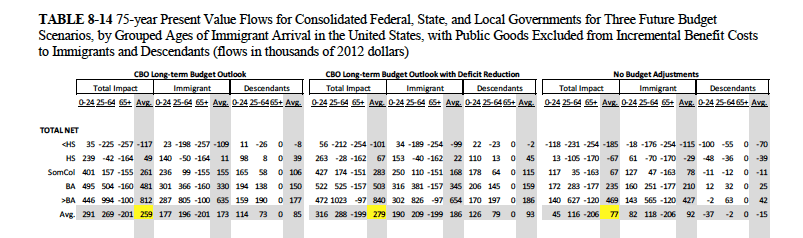

The critical number is “231,” which is buried in the seventh”no budget adjustments” column of a table on page 349. It shows that taxpayers must put aside $231,000 in a 3 percent interest-paying account to fund 75 years of future spending on healthcare, education for the immigrants’ children and much else, whenever a low-skilled immigrant crosses the border.

So whenever four unskilled immigrants from Central America get residency, Americans have to put aside almost $1 million to pay their costs over the next 75 years. Since 2012, President Barack Obama has allowed roughly 400,000 migrants from Central America into the United States to seek Green Cards. Only a tiny percentage has been sent home.

The tax picture does improve if the immigrants have college degrees, allowing them to pay more in taxes than they receive in benefits over the next 75 years.

But even that tax benefit comes at a huge cost to working Americans. That’s because the extra inflow of migrants annually shifts $500 billion in wages from ordinary Americans and established immigrants, over to new lower-wage immigrants and the companies that hire them, according to the data in the report.

The academies’ report has been finished for a few months, but its release has been delayed until late in the 2016 campaign. Supporters of immigration must hope journalists will cherrypick a few favorable numbers from the huge report, which also obscures the huge cost of immigration in a poorly produced 495-page report.

For example, the estimated costs of immigration paid by state and local taxpayers is hidden deep in the huge and hard-to-read report.

The greatest tax costs are borne by Americans in Minnesota, where each new immigrant costs taxpayers roughly $5,100 per year, not counting the marketplace impact on displaced local workers. In D.C., the cost per immigrant is $2,800, it is $3,050 in Washington state, $2,050 in Texas, $1,250 in Georgia, and $3,650 in Wisconsin.

Some states make a slight profit per immigrant, partly because of lower welfare benefits, and partly because their state’s inflow is so low that it does not displace many local workers. For example, West Virginia gains $550 per immigrant, Oklahoma gains $200 per year per immigrant, and Alaska gains $3,950.

The total costs are not displayed in Table 9-6. But the per-immigrant costs can be multiplied by the number of immigrants in each state, which is shown later in the report in Table 9-13.

So the cost to adding diversity to California adds up to $19 billion per year, while Texans collectively pay $9.8 billion for the privilege of delivering new workers and customers to local businesses.

Illinois taxpayers pay roughly $.2 billion for ethnic vibrancy, Washington State taxpayers write checks for $2.5 billion to import apple-pickers and other workers, and New York residents pay $5.8 billion to keep New York city supplied with low-wage workers.

The costs of second-generation immigrants, says the report, are modestly offset by their annual tax payments, generating a modest surplus of $30.5 billion per year for state and local taxpayers. That means the cost of supporting the first generation of immigrants — and educating their children — won’t be fully paid in the lifetime of their children.