The motif of the 2016 presidential election has emerged as one of rebellion against the establishment and the oligarchy that perpetuates it.

The larger question is whether some politically amorphous dissident army can upend the status quo. The establishment’s horror at the prospect of a successful rebellion belies the history of a nation that was actually founded in such rebellion.

The ghost of rebellion that haunted the English psyche for centuries and that they were determined to crush in 1776 was named – Jack Cade. Have you ever heard of him?

You see, in 1450, Cade led a makeshift rebel army against the forces of King Henry VI. He was almost certainly a peasant, but other than that, very little is known about him, which enabled him to shape shift like a specter of discontent. According to some, Cade was plotting with Richard of York under the name “John Mortimer.” According to others, he was Dr. Alymere, son-in-law of a Surrey squire, and still others believed he was a practitioner of witchcraft.

Jack Cade’s real name is unknown to this day, as is his history prior to 1450. He appeared, it seems, out of nowhere in the human form of Jack Cade, or whomever, to haunt the kingdom into chaos.

What is known about Jack Cade is that he led a threateningly large group of peasants, small land owners, some clergy and even some propertied men to the gates of London, mostly in rebellion against taxation from the Hundred Years’ War and pervasive government corruption. This group of minor gentry and land laborers did not seek sweeping social change as much as basic government reform, mostly in the form of lower taxes.

Upon first hearing of the peasant rebellion, the King sent his troops to Sevenoaks; about 18 miles southeast of London, to strike down the ragtag reformers, and the king’s troops were promptly defeated.

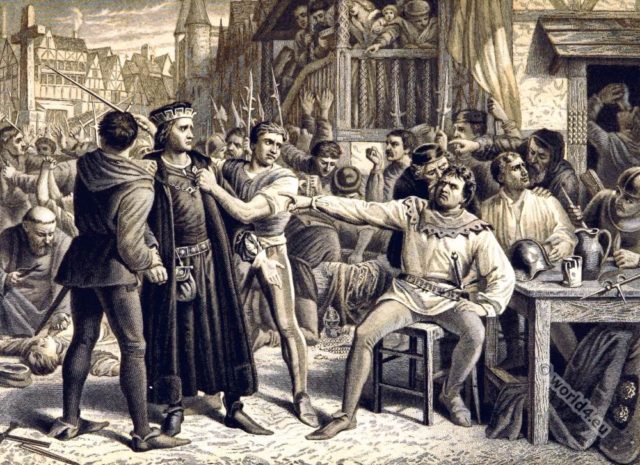

Cade’s impromptu army marched to London where they were treated as victors; Londoners generally agreed that taxes and corruption were pressing problems. Cade’s army became rather enamored with their success and proceeded to storm the Tower of London and behead a few government officials, including Sir James Fiennes, the king’s treasurer, and Sir James’ son-in-law, William Crowmer. The bodiless heads of Fiennes and Crowmer were placed atop stakes and paraded through town kissing each other. For good measure, Cade’s men also killed the Sheriff of Kent who, needless to say, had some intent to arrest Cade.

The king’s men regrouped and fought again but could gain no ground on Cade’s army of malcontents, at which point Cade presented his list of demands to royal officials who agreed to the demands and to granting pardons to the rebellion’s participants. The demands can be summarized simply as “run a decent government.” With an agreement on the demands, the rebel army largely dispersed.

King Henry, though, had no intention of meeting the rebel army’s demands – either to run a decent government or pardon Cade and his men. The new Sheriff of Kent chased Cade for forty miles until he finally arrested Cade with a fatal blow of a sword. To further punctuate his rejection of the agreement he’d supposedly accepted, King Henry subjected Cade’s dead body to show trial, and, upon being found guilty, Cade’s corpse was hung, and then cut into pieces that were distributed throughout Kent as a cordial reminder of the king’s disposition on peasant rebellions. Finally, Henry had Cade’s head staked on a pole on London Bridge, kissing no one.

The specter of Cade’s peasant rebellion has haunted English historians and poets ever since: “For our enemies shall fall before us, inspired with the spirit of putting down kings and princes…” (Henry VI, Part 2).

Peter Oliver, the loyalist Chief Justice of the Massachusetts court wrote in his 1781 Origin & Progress of the American Rebellion: “[T]he Hydra was roused. Every factious Mouth vomited out Curses against Great Britain, & the Press rung its changes upon Slavery. A Mr. Delany a principal Lawyer of Virginia, wrote the first Pamphlet of Note upon the Subject; which, as soon as it reached Boston young Mr. Otis, the then Jack Cade of the Rebellion.”

More frightening to the oligarchs than the specter of Jack Cade was the idea of Jack Cade with a printing press marshaling a literate rebellion. Sending the Sheriff of Kent to arrest Cade with a blow of a sword would do no good, because as John Milton observed a century earlier: “Books are not absolutely dead things, but doe contain a potencie of life in them to be as active as that soule was whose progeny they are.”

If knowledge had become untethered from a world of fixed relationships, and its value increasingly was not in the degree to which it supported and completed a stable and fixed edifice of knowledge, and if books were not dead things, then how was the Sheriff of Kent to respond? He could hardly chase down an idea and put it to the sword.

Peter Oliver’s evocation of Jack Cade as “The Hydra” demonstrates that in the new media world of the 18th century, the press could create many-headed ideas incapable of being terminated by a Sheriff’s swift sword.

But the foundation of colonial education was in fact the Bible, and Oliver was undoubtedly referencing the Book of Revelations hydra and fully intended his readers to think of the Judgment Day beast. Only an oligarch would apply the metaphor to the many printing presses fueling the media war and not to the Empire that wished to return to the days when rebellion could be quelled by putting a single man to death.

In the end, Oliver’s interpretation lost and the rebel’s version of the hydra was memorialized in the American founding document, namely: The Declaration of Independence (“He has erected a multitude of New Offices, and sent hither swarms of Officers to harass our people and eat out their substance”).

The colonial oligarchs of the 1700s had feared the press would transform the specter of Jack Cade into an irresistible force of history. When the Prime Minister requested that King George charge Otis – the “Jack Cade of the Rebellion” – with treason (a crime only cured by execution), the King demurred. It was too late. Though the King still harbored hopes of regaining control of colonial Boston, easy access to the press had transformed Otis’ rebellion far beyond anything readily solvable with a sword.

In the end, Jack Cade vanquished the hydra with the consequential help of new media. And if Otis had Twitter, the King’s hopes for regaining control may have been dashed well before 1776.

The distinction between the failure of Cade’s rebellion and the success of the American Revolution is before our very eyes today.

Bernie Sanders will agree to a few committee assignments at the DNC convention and then be hunted by the Clinton machine like Cade through the woods of southern England.

Trump however, is a leader of a different kind of populist rebellion – one that understands that in order to be effective the rebellion must leverage media to become a movement that lives in ideas rather than through any individual.

Ironically, this makes Trump not a dictator (where the power resides in the person) but rather a true child of the American Revolution (where the power resides in ideas promoted through the media). Trump’s power is generated by his persistent refusal to come to agreements with the oligarchy and established elites because, unlike Jack Cade, Trump’s peasants won’t get fooled a second time.

Nathan Allen is a Yale graduate writer who lives in Connecticut.

Theodore Roosevelt Malloch is a professor at Oxford University and author of a new memoir, DACVOS, ASPEN & YALE: My Life Behind the Elite Curtain as a Global Sherpa, 2016.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.