Industry executives and university advocates have successfully duped nearly every reporter, editor and anchor nationwide about the scale and purpose of the H-1B professional outsourcing program.

The journalists–and Americans—have been kept in the dark while universities and many allied name-brand companies have quietly imported an extra workforce of at least 100,000 lower-wage foreign professionals in place of higher-wage American graduates, above the supposed annual cap of 85,000 new H-1Bs.

Less than one-sixth of these extra 100,000 outsourced hires are the so-called “high-tech” computer experts that dominate media coverage of the contentious H-1B private-sector outsourcing debate.

Instead, the universities’ off-the-books H-1B hires include 21,754 professors, lecturers and instructors, 20,566 doctors, clinicians and therapists, 25,175 researchers, post-docs and biologists, plus 30,000 financial planners, p.r. experts, writers, editors, sports coaches, designers, accountants, economists, statisticians, lawyers, architects, computer experts and much else.

See here for an NPR story on H-1B outsourced jobs sought by young American female scientists.

These white-collar guest-workers are not immigrants — they are foreign professionals hired at low wages for six years to take outsourced, white-collar jobs in the United States. Many hope to stay in the United States, but most guest-workers return home after six years. The universities have zero legal obligation to recruit Americans for the jobs given to the foreign professionals. There’s good evidence that the H-1B graduates cut payroll costs, and there’s little or no evidence that they create additional jobs or file additional patents.

The white-collar guest-workers are a majority of the nation’s unrecognized workforce of roughly 2 million foreign temporary-workers, and they’s replacing experienced American professionals — plus their expensively educated children, and the upwardly striving children of blue-collar parents — in the declining number of jobs that can provide a rewarding and secure livelihood while the nation’s economy is rapidly outsourced, centralized and automated.

The American professionals who are displaced from these prestigious university jobs don’t just go into the woods and die. They migrate down into other sectors, such as advocacy and journalism, or step down to lower-tier colleges and companies, where the additional labor-supply drives down white-collar wages paid by other employers.

So how does this off-the-books army of foreign professionals get to take jobs in the United States?

The Fake H-1B Cap

The media almost universally reports that the federal government has set a 65,000 or 85,000 annual cap on the annual number of incoming H-1B white-collar professionals.

Here’s the secret — the H-1B visas given to university hires don’t count against the 85,000 annual cap, according to a 2006 memo approved by George W. Bush’s administration.

Basically, universities are free to hire as many H-1Bs as they like, anytime in the year, for any job that requires a college degree.

The university exemption is so broad that for-profit companies can legally create affiliates with universities so they can exploit the universities’ exemption to hire cheap H-1B professionals. From 2011 to 2014, for example, Dow Chemical, Amgen, Samsung and Monsanto used the university exemption to hire 360 extra H-1B professionals outside the 85,000 annual cap.

That’s not an abuse of the law. It is the purpose of the 2006 memo, and it is entirely legal — providing the foreign professional allocates at least 55 percent of his or her time to work with a research center that is affiliated with a university. Even if an H-1B working at a university’s medical center is hired away by a company that works with the medical center, he’s still exempt from the annual cap.

Each foreign professional with a H-1B visa can stay for three years, and then get another three-year H-1B visa.

All told, the universities and their corporate allies brought in 18,109 “cap exempt” new H-1Bs from January to December 2015. They brought in 17,739 new H-1Bs in 2014, 16,750 in 2013, 14,216 in 2012, 14,484 in 2011, and 13,842 in 2010, according to a website that tracks the visas, MyVisaJobs.com. That’s an accumulated extra resident population of up to 95,140 foreign professionals working in universities in 2015.

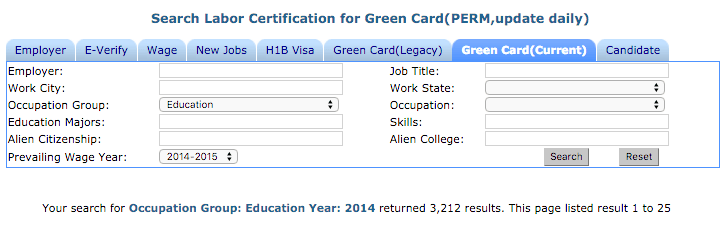

Here’s a partial list of H-1B approvals, sorted by university for 2013 and 2014.

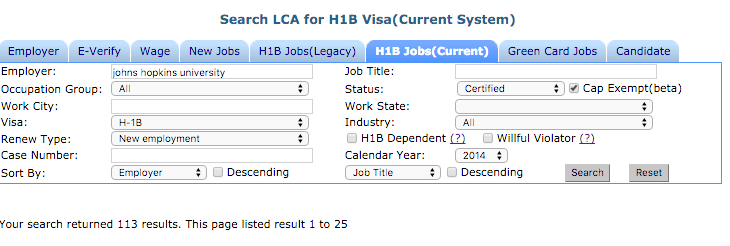

The MyVisaJobs.com website shows that the University of Michigan got 165 new H-1B hires in 2014. Harvard brought in 162, Yale hired 132, and so forth. Over the five years up to 2015, Johns Hopkins University accumulated a battalion of roughly 885 new H-1B professionals. That’s 885 prestigious and upwardly mobile jobs that didn’t go to debt-burdened American college-grads.

The full annual inflow of H-1Bs seems to be even higher than the 85,000 plus the extra university inflow, according to government reports.

Some data is provided in this series of annual reports. In fiscal 2014, for example, 124,326 new H-1Bs visas were approved. That’s far above the 105,000 combination of the supposed 85,000 a year cap and the universities’ almost-20,000 extra H-1Bs. The 19,000-visa gap is waived away by H-1B advocates as duplication and unused visas.

The numbers of “cap exempt” H-1Bs are also shown in the federal reports, such as this 2014 report and this 2013 report, but the numbers are broken up and unexplained.

The numbers are collated and displayed by many websites used by foreign people looking for H-1B jobs, such the myvisajobs.com, H1Base.com and the visasquare.com sites, and by various critics.

There are no significant curbs on this H-1B middle-class outsourcing. For example, salary levels can be set very low and universities do not have to first offer the jobs to Americans. In fact, the system is so lax that federal government rejects only about 5 percent of the universities’ applications for foreign professionals.

The Fake Six-Year Limit

But that’s not all. Nearly all journalists say the H-1B workers can stay for six years. Wrong. Many stay for longer — and a large number also get long-term work-permits and Green Cards that give them residency and a path to citizenship.

Foreign professionals can convert H-1Bs into permanent Green Cards if their employers file paperwork. The process can take a few years to complete, so the federal government allows H-1B professionals to get additional one-year H-1Bs visas to stay in their jobs until they get approval for a Green Card.

Breitbart asked the Department of State for the number of one-year H-1B visas awarded each year, they refused to say. “We don’t track that specific visa statistic,” said an official who did not want to be named.

But the databases show some of the numbers. Universities have requested 30,000 Green Cards for foreign workers since 2009. That includes 16,941 “education” workers and roughly 12,000 researchers, according to myvisajobs.com website.

That 30,000 number does not include any of the many former H-1B professionals who got their Green Cards prior to 2009.

Outside the universities, for-profit companies annually apply for roughly 60,000 Green Cards, many for current H-1Bs.

The availability of Green Card upgrade means that many foreign H-1Bs professionals get a series of one-year H-1B extensions even after staying for six years. That process bumps the annual production of H-1B visas further above the supposed annual 85,000 cap.

That Green Card inflow means that tens of thousands of younger American graduates lose upwardly mobile jobs in the private sector to cheaper competition, while foreign competitors simultaneously cooperate and compete to bring in their friends and allies, including many from their home countries.

Advocates for foreign hiring say the foreign graduates develop new products and nudge up productivity, so creating more jobs for Americans.

That’s got to be true — to some extent. But it is offset by the reality of displaced Americans who are not using their expensively earned skills. This United States now has a surplus of would-be professors, science post-docs and other graduates who are now stuck working as baristas, clerks, journalists and underpaid adjuncts because of the universities’ army of foreign professionals.

The Mini H-1B Program

But that’s not all. There’s another little-known guest-worker program which critics call the mini-H-1B.

That’s the so-called “Optional Practical Training’ program, which allows foreign graduates of U.S. universities to work for 12 months or 29 months in the United States. Without approval from Congress, the program was created by George W. Bush’s appointees and is being expanded to 36 months by President Barack Obama’s appointees. In 2014, the controversial program allowed 120,000 foreign graduates to work at a very wide variety of U.S. jobs, sometime for employers who discriminate against Americans.

Many of these foreign graduates are trying to land a multi-year H-1B job.

Universities love the OPT program because it allows them to effectively sell U.S. work-permits to foreign students, and rent foreign students to companies. “We are very supportive of giving international students more opportunities because they are our alums, they are our graduates, they are the ones that are going to get better jobs because the companies are going to see that there’s more longitude to it,” Adria Baker, the director of Rice University’s office for international students.

“The companies are depending on these students. They hire them because they are the best people for that field,” she said.

Foreign students openly say they pay U.S. universities for the paperwork needed to work and stay in the United States. “The primary reason I chose the U.S. was exactly that it offers better opportunities than other countries, whose immigration policies may be stricter,” Maggie Tang, a 2015 graduate of Rice, told the university newspaper. “I knew I had a chance to stay here and work, to earn back some of that tuition and gain experience,” she said.

Rice University also uses H-1Bs.

The OPT system is also used to sneak foreign-tech workers into the U.S. economy via visa-for-tuition universities. In December, U.S. border officials blocked entry to a group of Indian students enrolled at two low-status California universities.

There’s no data on the employment of the OPT guest-workers. Most seem to work in computer and software jobs, but many also work for 12 months in non-tech jobs. But if only 5 percent are employed at universities or university-affiliated centers, that translates into 6,000 more university jobs that American graduates cannot earn.

That’s still not all!

The L-1 visa is used by companies to transfer managers into the United States. From 2009, to 2013, almost 70,000 were awarded each year, each lasting up to seven years. That adds up to a total between 300,000 to 400,000 foreign managers and executives working in the private sector. An unknown percentage work in the universities. If that visa category did not exist, foreign companies would be under more pressure to hire a few hundred thousand American business graduates, engineers and scientists for those jobs — and to bid up salaries for professionals at universities.

There’s More!

In early 2015, Obama’s deputies unilaterally began granting work permits to the spouses of H-1B professionals, despite the lack of congressional approval.

“Finalizing the H-4 employment eligibility was an important element of the immigration executive actions President Obama announced in November 2014. Extending eligibility for employment authorization to certain H-4 dependent spouses of H-1B nonimmigrants is one of several initiatives underway to modernize, improve and clarify visa programs to grow the U.S. economy and create jobs,” said the February statement.

The agency “estimates the number of individuals eligible to apply for employment authorization under this rule could be as high as 179,600 in the first year and 55,000 annually in subsequent years,” it said.

The vast majority of all H-1Bs working in the United States — estimated to be roughly 600,000 — work for companies outside universities. So the number of H-1B spouses at universities is perhaps 10,000 per year, or 60,000 over six years. In only one-in-ten of those foreign spouses get a white-collar job at a university, that’s another 6,000 university jobs that can’t be won by a struggling American graduate trying to pay off their college debt.

That’s still not all!

A draft regulation released Dec. 31 by Obama’s deputies at the Department of Homeland Security would allow many more Indian and Chinese H-1Bs to get Green Cards, and also allow many more companies to import H-1B workers outside the supposed 85,000-per-year cap — if they just ink a deal with a university.

The draft regulation declares that “based on its experience in this area, DHS believes that the current definition for “affiliated or related nonprofit entities” does not sufficiently account for the nature and scope of common, bona fide affiliations between nonprofit entities and institutions of higher education. To better account for such relationships, DHS proposes to expand on the current definition by including nonprofit entities that have entered into formal written affiliation agreements with institutions of higher education.”

Add It Up

This data shows that universities have effectively outsourced 125,000 prestigious university jobs to foreign professionals, with the full support of the federal government, and amid the complete obliviousness of the U.S. media industry.

The 125,000 total is a reasonable accumulation of 90,000 H-IB workers, 30,000 post-2009 Green Card recipients and applicants, plus just 6,000 workers via the OPT, H-1B spouses or the J-1 “academic training” visa avenues.

Of course, this 125,000 total is only about one-tenth of the roughly 1.2 million foreign, professional guest-workers holding jobs in the United States. That broader estimate is based on a population of 95,000 H-1Bs at universities, 550,000 H-1B professionals at for-profit companies, 120,000 OPT graduates, 350,000 L-visa holders, plus many other professionals with free-trade, J-1 and O visas.

That 1.25 million is more than the roughly 800,000 Americans who graduate each year with degrees in business, medicine, engineering, science, software and architecture. Roughly one-third of these 1.25 million foreign professionals work as lower-status, lower-pay, lower-skill, back-office computer experts.

But at least one-third of these 1.25 million foreign professionals work in prestigious U.S. professional jobs that are the best pathway to prosperity in an increasingly turbulent, winner-take-all, risky, global economy.

Ironically, the proliferation of long-term white-collar guest-workers means that there are far more wage-cutting, professional-grade guest-workers in the United States that there are short-term blue-collar guest workers in agriculture or blue-collar jobs. Basically, the American professional sector is being hit harder by foreign guest-workers than the lower-middle-class and blue-collar Americans which are being hit by guest-workers in slaughterhouses, country clubs, landscaping firms and construction sites.

This huge white-collar guest-worker force is only part of the labor-market impact of foreign workers. In 2013, 2 million new foreign workers entered the country just as four million young Americans began looking for their first jobs. That year, wages flatlined, corporate profits rose and stock market spiked.

So Which Journalists Missed This Hidden University Workforce?

Practically every newspaper, online news-site, wire-service, TV network, and every journalist and talking-head in the media business, has been kept in the dark and fed shady H-1B data by advocacy, business and university groups.

According to Google, the New York Times has not ever produced even one article with “cap exempt” and “H-1B.” There are two mentions of that combination at the Washington Post — but they’re both in job ads, not news reports. Google itself has only 95 mentions of that combination in reports, all from specialist publications.

This means the natural debate over middle-class H-1B outsourcing has been sidetracked by clever advocates — and gullible reporters — into a boring, complex, semi-technical dispute over the hiring of low-status computer-experts by Facebook and various unfamiliar outsourcing companies. That clever strategy has completely hidden the huge impact on Americans by their quiet exclusion from many good jobs — professors, clinicians, business majors, researchers and designers — that are the pathway to professional success.

Let’s go through a few of the wrong reports.

Vox’s Dara Lind, wrote in April that “last year, the government received twice as many applications in the first week as the 85,000 visa slots available.”

Politico’s Seung Min Kim wrote in March 2015 that “the H-1B cap is set at 65,000 annually, though an extra 20,000 visas are set aside for immigrants with a master’s degree or higher from a U.S. school.”

AP reporter Joyce Rosenberg wrote in April 2015 that “Congress set a limit of 65,000 for visas for workers with bachelor’s degrees, and 20,000 for those with master’s degrees.“ AP reporter Erica Werner wrote “all 85,000 visas” in April 2014. AP writer Kevin Freking reported in March 2015 that “a bill… would expand the current annual cap on H-1B visas from 65,000 to between 115,000 and 195,000 visas.” Other news accounts were very different.

Bloomberg’s Sahil Kapur has repeatedly claimed the H-1B program is limited to 65,000 imports a year, and wrote in August 2015 that “the Chamber of Commerce and Silicon Valley are instead pushing to ease H-1B restrictions and raise the general quota of 65,000 immigrants per year.”

At the Washington Post, reporters David A. Fahrenthold, Sean Sullivan and Hayley Tsukayama, plus Dan Balz, Jose A. DelReal, Jenna Johnson, Jerry Markon, Ed O’Keefe and Katie Zezima, put their name to an article that declared The H-1B visas “are now capped at 65,000 per year.”

An April 2015 report by by Reuters’ Eric Walsh declared that “a maximum of 85,000 of the work visas, including 20,000 for holders of master’s degrees, are available each year under limits set by Congress, despite years of heavy lobbying by tech companies to raise the cap.”

At Slate.com, Will Saletan declared in Nov. 2015 that Sen. Ted Cruz proposed amendments in 2013 that would have “quintupled the number of H-1B visas (from 65,000 to 325,000 per year).’

At National Journal, Fawn Johnson wrote that the H-1B program is “limited to 85,000 for the entire 2014 fiscal year [and] the visas are expected to run out within a few weeks.” She also said that critics of the program are “H-1B haters.” NJ’s Beth Reinhard and Chris Frates also fell for the spin.

At TheHill.com, Julian Hattem reported in January 2015 that “current law caps the number of high-skilled workers allowed into the U.S. under the H-1B visa program at 65,000 per year.”

For ABC, Huma Khan wrote in February 2012 that “sixty-five thousand H1B visas are given to companies every year, and 20,000 are given to foreign workers with a U.S. master’s degree or higher.”

For NBC news, Frances Kai-Hwa Wang wrote in April 2015 that “after about 233,000 H-1B visa applications outstripped the cap of 65,000 in less than a week for the third year in a row, business and economic leaders across the Midwest—including Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and New York—spoke out on the need for H-1B visa reform.”

In April 2013, CBSnews.com posted an Associated Press report by Matt York, declaring that “each year 65,000 visas are awarded to companies looking to hire high-skilled workers from around the world; 20,000 more visas are available specifically for foreign workers who have earned a master’s or another advanced degree from a U.S. university.”

Amusingly, this secret H-1B system has been operating under right outside the front doors of famous journalism schools.

The University of Missouri is home to the Missouri School of Journalism, but from 2010 to 2015, the university hired 498 H-1Bs, including educators, life-science researchers and health-care specialists, plus economists, psychologists, database administrators, student advisors, marketing analysts, and information technology experts. Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism lies within a university that won 829 H-1Bs from 2010 to 2015, including educators and life-science researchers.

Unsurprisingly, this journalist has written many articles on the H-1B program without recognizing the scale of the universities’ loophole, despite a prominent interest in the nation’s cheap-labor policies. This author also missed the growth and impact of the H-2B blue-collar outsourcing program, which has been well covered by Buzzfeed.

How Did the H-1B Advocates Successfully Mislead the Media?

Pro-immigration business lobbyists have repeatedly and routinely misled journalists about the scale and purpose of the H-1B program.

Why? Because that’s where the money is. Every cut to professionals’ salaries is a pile of cash that can be directed somewhere else.

How did they mislead journalists? Not by lying, but by misdirection.

Basically, the executives and advocates have constantly spotlighted the arguments over supposed annual caps of 65,000 and 85,000, have constantly hustled journalists to focus on computer and software ”shortages,” and have rarely even hinted at the existence of the huge university exemption.

Mark Zuckerberg’s FWD.us lobbying group — mostly funded by Silicon Valley billionaires — frequently pushes the 85,000 number, even in open letters to politicians, such as Sen. Richard Shelby and former Rep. Ron Barber. According to Google, the group has mentioned the cap exemption only once, in passing, in a story about one would-be migrant.

Several other billionaires, including Mike Bloomberg, Bill Gates and Rupert Murdoch, created the ‘Partnership for a New American Economy” to increase immigration of workers and consumers. A Google search of the group shows 70 results with H-1B and 85,000 — “Last year, for instance, 172,000 applications were received in a single week for just 85,000 slots” – but only one document that briefly cites the cap-exempt status in technical notes.

FWD.US and the Partnership group did not respond to emails from Breitbart.

The Business Roundtable offers 29 mentions of H-1B and 65,000, but no mention of the universities’ exemption, according to Google. Instead, reporters were fed the usual — “With the announcement today that both the 65,000 and 20,000 H-1B visa caps for fiscal year 2016 have been reached, Business Roundtable CEOs made a renewed call for Congress to fix a broken immigration system that keeps U.S. companies from hiring the top world talent they need,” one 2015 press release claimed.

The U.S. Chamber has pushed the H-1B program strongly, but has mentioned the cap exempt program only once in a dense 14-page report about the 2013 amnesty-and-immigration bill.

The same pattern repeats at the Brookings Institution, with 37 mentions of H-1B and 65,000, but only one 2009 mention of the cap exempt side. Brookings did describe the cap in this long report, but offered no data.

A Google search shows 213 hits for both H-1B and 65,000 at the Migration Policy Institute — “ an independent, nonpartisan, nonprofit think tank in Washington, DC… guided by the philosophy that international migration needs active and intelligent management“ – but only one mention of the “cap exempt,” hidden deep in a 2004 report.

The American Immigration Law Association showed 212 links mentioning H-1B and 65,000, and 48 mentions of the “cap exempt” program. Most of the mentions provide professional advice to practicing lawyers. A search that looked for mentions of the group’s communications director, George Tzamaras and the program showed 17 mentions of H-1B and 65,000, but zero mentions of “cap exempt,” even though he issued detailed descriptions of the H-1B program.

The group’s incoming president, William Stock, told Breitbart that many fewer H-1B take up jobs than get visas, partly because employers and prospective employers change their plans during the process. “There are plenty of H-1B petition approvals that don’t ever result in a new H-1B worker,” he said, but he declined to estimate how many new H-1Bs arrive each year.

The site operated by progressive open-border group, americacasvoice.org, has 49 mentions of the H-1B program, but none of the cap-exempt loophole.

The universities’ advocacy group, the American Council on Education, has six mentions of the H-1B program, including one letter urging passage of a bill that would allow an unlimited number of H-1Bs for private sector employers. But the site does not mention the “cap exempt” term.

The Association of American Medical Colleges, which advocates for medical-research universities, did explain the cap-exempt issue in a 2011 post. But the group keeps a very low profile on the H-1B issue.

Some loud advocates for the H-1B program knew of the exemption, but still kept journalists in the dark.

Marshall Fitz was the director of immigration policy at the Center for American Progress in 2012 when put out a 33-page paper urging an expansion of the H-1B and other high-skill programs. “Fitz has been one of the key legislative strategists in support of comprehensive immigration reform… [and] he served as the director of advocacy for the American Immigration Lawyers Association, where he led the education and advocacy efforts on all immigration policy issues for the 11,000-member professional bar association,” says his bio. He did not mention the cap exempt program in his 33-page paper. “We actually don’t have much current work on this topic so it doesn’t look like I’ll be your best resource for this particular piece,” spokeswoman Tanya Arditi told Breitbart.

Alex Nowrasteh, an open-borders activist at the libertarian CATO Institute, has often touted the 85,000 number and did briefly cite the cap-exempt H-1Bs in a November 2014 paper. When Breitbart asked Jan. 4 if “we are getting almost 50 percent more H-1Bs each year than the media and the public knows,” he responded, saying “that might be fair with some caveats.”

“Most policy makers aren’t too concerned about labor market competition at non-profits and universities,” Nowrasteh added.

This H-1B fight — and the broader disputes over the annual inflow of 700,000 guest-workers in numerous categories — doesn’t follow partisan lines.

Among the politicians calling for less use of guest-workers are far-left Sen. Bernie Sanders, plus conservative Sen. Ted Cruz and GOP 2016 frontrunner Donald Trump. In Congress, conservative Sen. Jeff Sessions and Sen. Chuck Grassley work for reforms with liberal Sen. Dick Durbin, the third-ranking Senate Democrat. In turn, politicians who are backing extra inflow of foreign workers include Republicans Sen. Marco Rubio, House Speaker Paul Ryan and Sen. Lindsey Graham, plus Democrat Sen. Barbara Mikulski.

Why Did Journalists Fall For The Spin?

Journalists are routinely hustled, steered and deceived on many issues, but rarely in such a complete and humiliating fashion. Why did so many journalists fail so completely?

In conversations with reporters, the university exemption “almost never comes up,” said Mark Krikorian, director of the Center for Immigration Studies. Few reporters cover the immigration beat with any depth, and most reporters “don’t feel the urgency to follow the money… [even though] they would do that kind of thing for Exxon or a Republican candidate,” he said.

Why not? Because reporters “see themselves on the same side as [foreign] people in this subject, so they don’t have the motivation” to examine the economic impact on Americans, Krikorian said.

Journalists have been fooled because they view foreign guest-workers as migrants, and they see issues about immigration as a civil-rights issue for migrants, not an economic issue about Americans, said Norm Matloff, a computer-science professor at the University of California, Davis, who often speaks to reporters. “I don’t find find them unsympathetic to [American] tech-workers… [and] most of them are generally bothered by it,” he said. “A lot of the journalists have spouses, sibling or cousins of even adult children that have had trouble getting work in the tech area [so] they’re not entirely unaware that there is a problem,” he said.

But that concern is modest, he said, adding “I would like to see outrage.”

The H-1B outsourcing issue doesn’t catch fire because for “the vast majority of journalists, if you flash the word ‘immigration’ front of them, they see it as a form of social justice,” not a middle-class economic issue,” he said.

The New York Times’s Julia Preston is a leading example. In 2013, at a semi-public event in Washington D.C., she described the push by business groups and progressives to win amnesty for the roughly 12 million migrants living in the United States as “a very substantial civil rights movement.”

Preston admitted that she empathized with the migrants. When covering a meeting of young advocates for illegal immigration, “seven hundred kids got out of their chairs and kind of came forward and… embraced [some of their] parents… and I’m just sitting there going, ‘How come I can’t get this kind of game from my daughter?’” she said. Her support for migrants is also driven by her employers’ ideology, she admitted. “There is a strong understanding on the editorial desk and at the masthead of the New York Times, that this issue is about the heart and soul of the United States, and who we are going to be as a nation going forward,” she said.

But she showed little sympathy for Americans. There’s a “popular resistance out in the country,” Preston complained. “It gets really ugly out there,” she said when describing Americans’ opposition to the 2013 amnesty-and-cheap-labor bill. However, since 2012, Preston has written several powerful articles about the H-1B’s impact on middle-aged American tech-experts at Disney, Southern California Edison and Toys ‘R’ Us. But has not mentioned the university exemption.

There are many other reporters who treat immigration only as a social-justice issue for foreigners — Elise Foley and Roque Planas at the Huffington Post, and Ed O’Keefe at the Washington Post, and Alan Neuhauser at USNews.com — rather than a profit-boosting policy for companies, a paycheck issue for Americans, or even a career problem for their own families’ children.

How Has The H-1B inflow Hit The Salaries of Americans Employed At Universities?

The extra supply of H-Bs drives down salaries for professionals in entry-level jobs, and it also cuts salaries for mid-career Americans in mid-levels jobs.

Many entry-level H-1Bs will beat entry-level Americans for an university job for huge reason — the hidden citizenship subsidy.

Foreign graduates will gladly take white-collar H-1B jobs at very low wages because the job puts them on the first step on the golden prize of a Green Card and citizenship. That’s a huge payoff for a few years of grinding work, because it would mean that all of that person’s descendants will be Americans, and also that their parents get to join the American retirement system.

In contrast, employers can’t pay American graduates this combination of low-salary plus the feds’ golden promise of citizenship — because the Americans already have citizenship. So the existence of the federal ‘citizenship subsidy’ means employers must pay more money to hire American college-grads than they would to hire foreign college-grads. That puts a huge disadvantage on American graduates, especially because many must ask employers for higher salaries to pay off their expensive U.S. college debt.

When entry-level wages drop, so do mid-level wages. That upstairs/downstairs link is not recognized by journalists, but it is a central issue for cost-conscious employers.

The H-2B program is the blue-collar equivalent to the H-1B program. In December 2015, GOP and Democratic leaders bumped the program from roughly 60,000 workers per year to roughly 150,000 workers per year — and they also canceled a planned federal rule that would have raised wages paid to H-2B guest-workers to roughly $13.80 per hour. A pay-increase for H-2B workers “causes a ripple effect in all wages across the board,” complained Josh Denison, a landscaper in Oxon Hill., Md., who advocated against the increase. “If your $10.30 basic domestic or H-2B laborer has an arbitrary wage increase, then you have to adjust wages [upwards] across the board in a sliding scale to keep it fair and balanced. What happens to the $12 guy if the new guy is making more? And what happens to the $15 guy?”

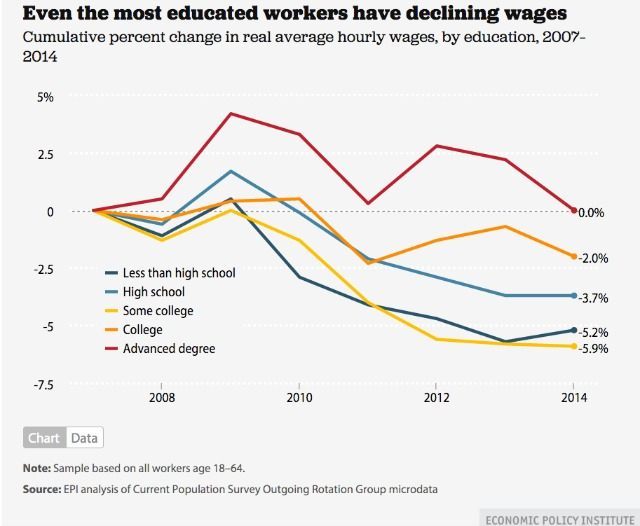

National wage-data is compatible with Denison’s experience. Wages for high-school grads — who are impacted by low-skill migration — fell by 3.7 percent from 2007 to 2014, according to the Economic Policy Institute. For college-grads, salaries dropped by 2 percent. Salaries paid to people with post-graduate degrees were flat

OK, let’s get to the university salaries. This analysis relies on the university-supplied data, shown at the MyVisaJobs site. There may be some overlap of H-1B titles — for example, some professors may also act as clinicians — but this data is presented by work-areas, such as education, healthcare and life-sciences.

Teaching Salaries

From 2010 to 2015, universities hired 21,784 new H-1B foreign graduates for education jobs. They also requested Green Cards for 11,394 people with “professor” in their titles. Combine the H-1Bs and Green Card workers, subtract 15 percent for duplication and attrition, and the data shows that the universities have roughly 27,000 foreign professionals in university teaching jobs.

“In the six years since the Great Recession, real year-over-year faculty salaries have declined 0.12 percent… [even though] many have been working more hours than ever before,” according to the 2014/2015 report on faculty salaries by the American Association of University Professors. Many of these H-1B teachers are paid a little over $60,000 — which is basically the minimum allowed by federal rules. But it is also roughly $30,000 less than the pay and benefits to given to the lower-half of full-time American academics and teachers in 2014, according to the AAUP.

The huge labor supply has also reduced job security, benefits and tenure opportunities. “In 1975, 43% of U.S. college instructors were adjuncts or other contingent workers, including those who work part time and those who are full time but not on a tenure track… By 2011, that figure had risen to 70%,” according to a Feb. 2015 Wall Street Journal article.

Healthcare Salaries

The universities and affiliated hospitals also hired roughly 20,666 new H-1B doctors, therapists and other healthcare professionals from 2010 to late 2015. The universities asked for very few Green Cards for these clinicians.

Salaries paid to doctors at universities have stalled. The 2014 salary paid to new ‘resident’ doctors at hospitals run by university-run medical schools was $49,218. That’s similar to the $49,945 salary paid by state hospitals. But six years after graduation, doctors in state hospitals have risen to $61,272, while medical-school doctors are paid almost $3,000 less, or $58,614.

It should be noted that American doctors’ salaries have already been reduced by a large inflow of foreign doctors, many through the J-1 ‘temporary’ visa program. In 2009, one out of every four doctors — or roughly 200,000 — were hired as foreigners, according to the American Association of Medical Colleges.

Research Salaries

The universities and affiliated biotech companies also hired 25,784 life-science researchers, post-docs and graduate students, and got Green Cards for another 9,000 scientists, many of them in the life-science sector. That leaves a 2015 foreign university-science workforce of roughly 29,000, assuming some departures.

The salaries paid to U.S. academic scientists have stalled.

Survey data shows that commercial employers pay far higher salaries than academic employers, and that average 2014 salaries didn’t exceed $60,000 until after age 34. In 2015, salaries jumped for many specialities, but rose by by an average of only 3.5 percent in the United States, but academic life-science salaries averaged out to $90,843, versus $131,079 in the commercial sector.

The university vs. commercial salary gaps are also visible at job-search sites, even though scientists in both workplaces perform similar work. An entry-level postdoc scientist in a university earns roughly $44,000, while new “research associate” at a minor drug-company earned $70,000.

In fact, there’s such an oversupply of life-science labor that many American bio-science grads never even get jobs in their chosen field, despite intense years of study through high-school and college. “Among biomedical science grads, only 59 percent landed in a job ‘closely related’ to their fields of study, down from more than 70 percent in 1997,” according to a 2012 report for the National Institutes of Health. In 2012, almost 60 percent of the bioscience degrees went to women.

“Every job that gets advertised get hundreds of applications,” said science-writer Beryl Lieff Benderly, who has been tracking the jobs pressures in the science sector as a writer for Science magazine. The inflow of H-1Bs, she told Breitbart, “is really driving down the entire wage-structure.”

The Targets of the H-1B Exemption

So let’s meet a few American victims of this post-graduate outsourcing process that journalists failed to notice — and failed to describe to Americans.

Scott Granneman is an untenured adjunct lecturer in St. Louis, who boosts his take-home pay by also working as an author and a consultant. He’s paid very little as an adjunct for teaching six courses — roughly $3,000 per class of roughly 45 students each — because “the universities realized it was far cheaper to do this with adjuncts,” he said. That’s possible because “there is a huge oversupply of labor,” he added.

But he had never heard of H-1Bs. “I had no idea about about that,” he told Breitbart. He teaches at Washington University in St. Louis, which brought in 529 new H-Bs from 2010 to 2015, including 130 new H-1Bs under the education “occupational group.” He also teaches classes at Webster University, which brought in six more education H-1Bs, including a game-design professor, during the same period.

When told about the H-1B inflow, Granneman – a liberal — equivocated. “I’m not against immigration at all,” he said, but “it is wrong in the sense that it is driving down the [salary] price for everybody.”

“Modest drinking is OK, getting drunk every day is not,” he added.

Mitch Tropin is an adjunct at several schools and was also unaware of the H-1B inflow, even though he’s been trying to unionize university lecturers. He’s met many foreign university employees, but “I never actually asked ‘Are you here through some sort of visa program,’” he told Breitbart.

He’s taught at Morgan State University, which imported 15 H-1Bs from 2012 to 2015, with salaries as low as $52,173, Loyola University, which imported 21 H-1Bs, with salaries as low as $74,619, Baltimore University, which brought in 2o H-1Bs, including two accounting professors, with salaries as low as $45,397, and Montgomery College in Maryland, which hired seven H-1Bs, including math professors, with salaries as low as $59,219. “I’m of a generation that always saw rising wages, and the current generation of young people have no guarantee,” Tropin said.

In September 2014, National Public Radio ran a segment lamenting “Too Few University Jobs For America’s Young Scientists.” The segment focused on two aspiring women scientists— both of whom have since been pushed away from laboratory science.

One woman scientist showcased by NPR is Vanessa Hubbard-Lucey, who also worked at NYU. She got her PhD in 2011, and turned 35 in 2014, when she left the NYU laboratory for a job at the Cancer Research Institute. From 2010 to 2015, the university hired 800 new H-1Bs, including 392 new life-science H-1Bs. Lucey declined to talk to Breitbart.

Victoria Elizabeth Ruiz worked as a post-doc researcher at the Blaser Lab at New York University’s school of medicine, where she also faced the 392 new life-sciences H-1Bs. Ruiz is now also working part-time as a low-wage adjunct for the City University of New York to gain teaching experience, she told Breitbart. Her resume says she has studied to win a science job since she enrolled as a science student at St. Johns University in 2003, and then as a PhD at Brown University, which brought in 45 life-science H-1Bs from 2010 to 2015.

On Jan. 25, after publication of the story, Ruiz emailed Breitbart, and asked to be removed from the story. “I honestly do not agree with the angle/tone of the article and would prefer not to be associated with it and have no comments on H1-B and the workspace,” she wrote.

But in October 2014, while working at NYU’s Blaser lab — whose staff includes foreign-born scientists — she posted a tweeted urging a reform of the nation’s scientist-training process.

http://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2014/09/16/343539024/too-few-university-jobs-for-americas-young-scientists

Follow Neil Munro on Twitter at @NeilMunroDC.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.