The Pacific El Niño weather pattern will likely provide rain to Texas and California, but worsen the current drought in southern America, and perhaps send a tsunami of poverty-stricken peasants northwards into the United States.

The U.S. National Weather Service announced there is now a 95 percent probability that the potentially most powerful El Niño on record will continue through the Northern Hemisphere during the winter of 2015-16, and only gradually weaken in the spring of 2016.

The current drought began in 2014, and Cuba and the Dominican Republic already have had to ration water supplies. Panama reduced the size of ships allowed through the Panama Canal. Low water-levels have threatened hydroelectric power generation across the region. El Salvador and the Dominican Republic are experiencing periodic blackouts.

The regions’ dry conditions from May through September appear to have damaged roughly half of the corn and a significant amount of the bean harvests. The prices of basic food staples rose 40 percent in some areas in 2014.

Poor climate conditions and high prices have left hundreds of thousands of families across the region without access to basic food necessities. Many subsistence farmers in Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador, do not have the money to buy food. The U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization estimated that nearly 1 million people in Guatemala do not have sufficient food. The longer the drought lasts, the greater the humanitarian disaster will become.

The northern migration may already have begun.

In 2014, President Barack Obama let roughly 130,000 Central Americans into the United States. Despite tougher security by Mexican police, another 25,000 have since been let through the U.S. border by Obama’s lax border policies.

In late 2014 and early 2015, despite strong pressure from voters, GOP leaders in Congress made only a half-hearted effort to tighten Obama’s lax enforcement of migration rules. The lax enforcement rules are backed by the GOP’s business donors, which gains extra customers and lower-wage workers.

Federal data on illegal migration is vague and months behind current events. But the D.C.-based Center for Immigration Studies estimates the population of foreign migrants in the United States grew by 790,000 since the beginning of 2014. That inflow is up sharply from the prior annual inflow of roughly 350,000 migrants per year.

During 2014, migrants from Central America overtook Mexico as the largest contributor of U.S. border apprehensions.

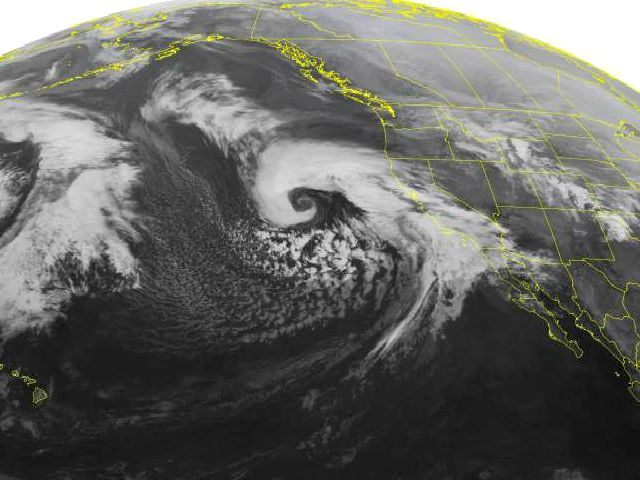

Because of El Niño, sea surface temperature “were near or greater than +2.0oC across the eastern half of the tropical Pacific” in August 2015, according to the NWS. Large subsurface temperature anomalies persisted in the central and east-central equatorial Pacific with the largest exceeding 6oC. The normal wind pattern was interrupted by “enhanced convection over the central and eastern equatorial Pacific that could cause a full reversal of the weather pattern and torrential rains to the West Coast. All models predict El Niño gaining strength.

The weather pattern shift has already started a drought in Central America and the Caribbean that are impacting Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Hispaniola and Cuba according to Stratfor Global Intelligence. Agricultural output is shriveling at a time when the area is still suffering from “a recent outbreak of coffee rust.” The scale of the drought in Central America has also led to higher homicide rates and drug-related violence.

During the 1997 and 1998 El Nino, fires that raged through Central America as the vegetation dried up. The smoke impacted the U.S. as far north as Oklahoma.

Three years later, the shortages of basic grains and vegetables were the worst since similar conditions 1,000 years ago led to the collapse of the 20 million population of the Mayan civilization that inhabited Guatemala, Belize and southern Mexico. Archeological evidence reveals massive deforestation during the period.

The dry season for Central America and the Caribbean runs from January through August.

El Nino will bring a better economic recovery to the U.S. West Coast over the next two years, but will increasingly devastate Central Americans. Facing starvation, millions of impoverished peasants may soon be headed for the United States.