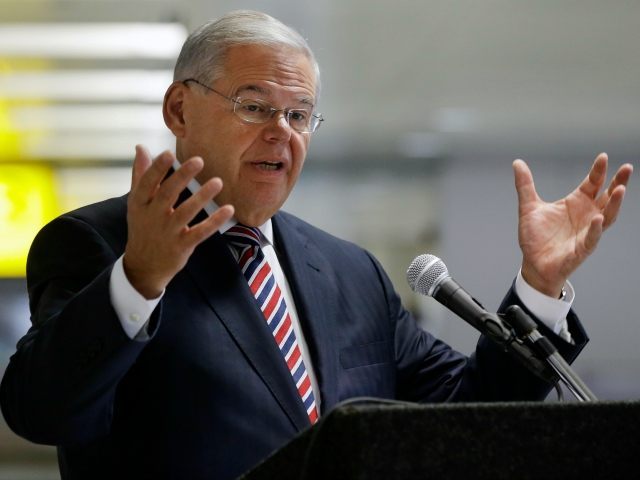

Senator Robert Menendez (D-NJ) announced on Tuesday that he is not supporting President Obama’s Iran deal, becoming the second Democratic Senator to do so, joining Sen. Chuck Schumer (D-NY) in refuting the accord.

Menendez joins a unified Senate Republican opposition. With news this week that Sen. Jeff Flake (R-AZ) will not support the deal, the president has likely failed to garner a single Republican vote in either chamber of Congress who favor the deal.

With Menendez, Schumer, and several House Democrats now officially opposed to the deal, President Obama’s Iran deal is now not only deeply unpopular with the American people, but also with a significant majority in Congress.

Menendez announced his opposition during a speech delivered at 1 PM on Tuesday at Seton Hall University’s School of Diplomacy and International Relations.

The New Jersey Senator argued that President Obama has continue to miscategorize opponents of the deal.

“Unlike President Obama’s characterization of those who have raised serious questions about the agreement, or who have opposed it, I did not vote for the war in Iraq, I opposed it, unlike the Vice President and the Secretary of State, who both supported it. My vote against the Iraq war was unpopular at the time, but it was one of the best decisions I have ever made,” Menendez said.

He added:

At the end of the day, what we appear to have is a roll-back of sanctions and Iran only limiting its capability, but not dismantling it or rolling it back. What do we get? We get an alarm bell should they decide to violate their commitments, and a system for inspections to verify their compliance. That, in my view, is a far cry from “dismantling.”

“As the largest State Sponsor of Terrorism, Iran – who has exported its revolution to Assad in Syria, the Houthis in Yemen, Hezbollah in Lebanon, and directed and supported attacks against American troops in Iraq — will be flush with money, not only to invest in their domestic economy, but to further pursue their destabilizing, hegemonic goals in the region,” he warned.

“Hope is part of human nature, but unfortunately it is not a national security strategy,” Menendez said, concluding his blistering critique of President Obama’s foreign policy.

Full Transcript below:

For twenty three years as a member of the House Foreign Affairs and Senate Foreign Relations Committees, I have had the privilege of dealing with major foreign policy and national security issues. Many of those have been of a momentous nature. This is one of those moments.

I come to the issue of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, with Iran, as someone who has followed Iran’s nuclear ambition for the better part of two decades. I decide on whether to support or oppose an issue on the basis of whether, it is in my judgment, in the national interest and security of our country to do so.

In this case a secondary, but important, question is what it means for our great ally — the State of Israel — and our other partners in the Gulf.

Unlike President Obama’s characterization of those who have raised serious questions about the agreement, or who have opposed it, I did not vote for the war in Iraq, I opposed it, unlike the Vice President and the Secretary of State, who both supported it. My vote against the Iraq war was unpopular at the time, but it was one of the best decisions I have ever made.

I also don’t come to this question as someone, unlike many of my Republican colleagues, who reflexively oppose everything the President proposes. In fact, I have supported President Obama, according to Congressional Quarterly, 98 percent of the time in 2013 and 2014. On key policies ranging from voting in the Finance Committee and on the Senate Floor for the Affordable Care Act, to Wall Street Reform, to supporting the President’s Supreme Court Nominees and defending the Administration’s actions on the Benghazi tragedy, his Pivot to Asia, shepherding the authorization for the Use of Military Force (AUMF) to stop President Assad’s use of chemical weapons, during the time I was Chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, to so much more, I have been a reliable supporter of President Obama.

But my support is not – and has not been driven by party loyalty, but rather by principled agreement, not political expediency. When I have disagreed it is also based on principled disagreement.

The issue before the Congress in September is whether to vote to approve or disapprove the agreement struck by the President and our P5+1 partners with Iran. This is one of the most serious national security, nuclear nonproliferation, arms control issues of our time. It is not an issue of supporting or opposing the President. This issue is much greater and graver than that.

For me, I have come to my decision after countless hours in hearings, classified briefings, and hours-and-hours of serious discussion and thorough analysis. I start my analysis with the question: Why does Iran — which has the world’s fourth largest proven oil reserves, with 157 billion barrels of crude oil and the world’s second largest proven natural gas reserves with 1,193 trillion cubic feet of natural gas — need nuclear power for domestic energy?

We know that despite the fact that Iran claims their nuclear program is for peaceful purposes, they have violated the international will, as expressed by various U.N. Security Council Resolutions, and by deceit, deception and delay advanced their program to the point of being a threshold nuclear state. It is because of these facts, and the fact that the world believes that Iran was weaponizing its nuclear program at the Parchin Military Base — as well as developing a covert uranium enrichment facility in Fordow, built deep inside of a mountain, raising serious doubts about the peaceful nature of their civilian program, and their sponsorship of state terrorism — that the world united against Iran’s nuclear program.

In that context, let’s remind ourselves of the stated purpose of our negotiations with Iran: Simply put, it was to dismantle all — or significant parts — of Iran’s illicit nuclear infrastructure to ensure that it would not have nuclear weapons capability at any time. Not shrink its infrastructure. Not limit it. But fully dismantle Iran’s nuclear weapons capability.

We said we would accommodate Iran’s practical national needs, but not leave the region — and the world — facing the threat of a nuclear armed Iran at a time of its choosing. In essence, we thought the agreement would be roll-back-for-roll-back: you roll-back your infrastructure and we’ll roll-back our sanctions.

At the end of the day, what we appear to have is a roll-back of sanctions and Iran only limiting its capability, but not dismantling it or rolling it back. What do we get? We get an alarm bell should they decide to violate their commitments, and a system for inspections to verify their compliance. That, in my view, is a far cry from ‘dismantling.’

I recall in the early days of the Administration’s overtures to Iran, asking Secretary of State, John Kerry, at a meeting of Senators, about dismantling Arak, Iran’s plutonium reactor. His response was swift and certain. He said: ‘They will either dismantle it or we will destroy it.’

I remember that our understanding was that the Fordow facility was to be closed – that it was not necessary for a peaceful civilian nuclear program to have an underground enrichment facility. That the Iranians would have to come absolutely clean about their weaponization activities at Parchin and agree to promise anytime anywhere inspections.

We now know all of that fell by the wayside. But what we cannot dismiss is that we have now abandoned our long-held policy of preventing nuclear proliferation and are now embarked – not on preventing nuclear proliferation – but on managing or containing it — which leaves us with a far less desirable, less secure, and less certain world order. So, I am deeply concerned that this is a significant shift in our nonproliferation policy, and about what it will mean in terms of a potential arms race in an already dangerous region.

While I have many specific concerns about this agreement, my overarching concern is that it requires no dismantling of Iran’s nuclear infrastructure and only mothballs that infrastructure for 10 years. Not even one centrifuge will be destroyed under this agreement. Fordow will be repurposed, and Arak redesigned.

The fact is — everyone needs to understand what this agreement does and does not do so that they can determine whether providing Iran permanent relief in exchange for short-term promises is a fair trade.

This deal does not require Iran to destroy or fully decommission a single uranium enrichment centrifuge. In fact, over half of Iran’s currently operating centrifuges will continue to spin at its Natanz facility. The remainder, including more than 5,000 operating centrifuges and nearly 10,000 not yet functioning, will merely be disconnected and transferred to another hall at Natanz, where they could be quickly reinstalled to enrich uranium.

And yet we, along with our allies, have agreed to lift the sanctions and allow billions of dollars to flow back into Iran’s economy. We lift sanctions, but — even during the first 10 years of the agreement — Iran will be allowed to continue R&D activity on a range of centrifuges – allowing them to improve their effectiveness over the course of the agreement.

Clearly, the question is: What do we get from this agreement in terms of what we originally sought? We lift sanctions, and — at year eight — Iran can actually start manufacturing and testing advanced IR-6 and IR-8 centrifuges that enrich up to 15 times the speed of its current models. At year 15, Iran can start enriching uranium beyond 3.67 percent – the level at which we become concerned about fissile material for a bomb. At year 15, Iran will have NO limits on its uranium stockpile.

This deal grants Iran permanent sanctions relief in exchange for only temporary – temporary — limitations on its nuclear program – not a rolling-back, not dismantlement, but temporary limitations. At year ten, the UN Security Council Resolution will disappear along with the dispute resolution mechanism needed to snapback UN sanctions and the 24-day mandatory access provision for suspicious sites in Iran.

The deal enshrines for Iran, and in fact commits the international community to assisting Iran in developing an industrial-scale nuclear power program, complete with industrial scale enrichment. While I understand that this program will be subject to Iran’s obligations under theTreaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, I think it fails to appreciate Iran’s history of deception in its nuclear program and its violations of the NPT.

It will, in the long run, make it much harder to demonstrate that Iran’s program is not in fact being used for peaceful purposes because Iran will have legitimate reasons to have advanced centrifuges and a robust enrichment program. We will then have to demonstrate that its intention is dual-use and not justified by its industrial nuclear power program.

What we get in return for removing sanctions is an inspection and verification regime of Iran’s somewhat-diminished, but still existent nuclear program, for which we will have to depend on Iranian compliance and performance for years to come.

A significant part of that performance is dictated by an Additional Protocol of the IAEA agreement that ensures access to suspect sites in a country. But Iran has agreed only to provisionally apply the Additional Protocol if Congress has abolished all sanctions. This could mean that if Iran has been sanctioned for violations of the agreement, Iran won’t even have to seek ratification of the Additional Protocol until those sanctions have been lifted – regardless of Iran’s full compliance.

This is hardly an ironclad commitment on which to base our right to inspect suspicious facilities. Of course if the Iranians violate the agreement and try to make a dash for a nuclear bomb, our solace will be that we will have a year’s notice instead of the present 3 months. So in reality we have purchased a very expensive alarm system. Maybe we’ll have an additional nine months, but with much greater consequences in the enemy we might face at that time.

But what happens in the interim? Within about a year of Iran meeting its initial obligations, Iran will receive sanctions relief to the tune of $100-150 billion in the release of frozen assets, as well as renewed oil sales of another million barrels a day, as well as relief from sectoral sanctions in the petrochemical, shipping, shipbuilding, port sectors, gold and other precious metals, and software and automotive sectors.

Iran will also benefit from the removal of designated entities including major banks, shipping companies, oil and gas firms from the U.S. Treasury list of sanctioned entities.

‘Of the nearly 650 entities that have been designated by the U.S. Treasury for their role in Iran’s nuclear and missile programs or for being controlled by the Government of Iran, more than 67 percent will be de-listed within 6-12 months,’ according to testimony before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, of Mark Dubowitz of the Foundation for the Defense of Democracies.

For Iran, all this relief comes likely within a year, even though its obligations stretch out for a decade or more.

Considering the fact that it was President Rouhani, who after conducting his fiscal audit after his election, likely convinced the Ayatollah that Iran’s regime could not sustain itself under the sanctions, and knew that only a negotiated agreement would get Iran the relief it critically needed to sustain the regime and the revolution, the negotiating leverage was, and still is, greatly on our side. However, the JCPOA in paragraph 26 of the Sanctions heading of the agreement, says:

‘The U.S. Administration, acting consistently with the respective roles of the President and the Congress, will refrain from re-introducing or reimposing sanctions specified in Annex II, that it has ceased applying under this JCPOA.’

I repeat, we will have to refrain from reintroducing or reimposing the Iran Sanctions Act I authored – which expires next year — that brought Iran to the table in the first place. In two hearings, I asked Treasury Secretary Lew and Undersecretary of State Wendy Sherman whether we in Congress have the right to reauthorize sanctions to have something to snapback to, and neither would answer the question, saying only that it was ‘too early’ to discuss reauthorization.

But, I did get my answer from the Iranian Ambassador to the United Nations who, in a letter dated July 25, 2015, said:

‘It is clearly spelled out in the JCPOA that both the European Union and the United States will refrain from reintroducing or reimposing the sanctions and restrictive measures lifted under the JCPOA. It is understood the reintroduction or reimposition, including through extension of the sanctions and restrictive measures will constitute significant nonperformance which would relieve Iran from its commitments in part or in whole.’

If anything is a ‘fantasy’ about this agreement it is the belief that snapback, without congressionally-mandated sanctions, with EU sanctions gone, and companies from around the world doing permissible business in Iran, will have any real effect.

The Administration cannot argue sanction policy both ways. Either they were effective in getting Iran to the negotiating table or they were not. Sanctions are either a deterrent to break-out, or a violation of the agreement, or they are not.

In retrospect, my one regret throughout this process is that I did not proceed with the Menendez-Kirk prospective sanctions legislation that would have provided additional leverage during the negotiations and would have also provided additional leverage in any possible post-agreement nullification by them or by us.

Frankly, in my view, the overall sanctions relief being provided, given the Iranian’s understanding of restrictions on the reauthorization of sanctions, along with the lifting of the arms and missile embargo well before Iranian compliance over years is established, leaves us in a weak position, and – to me – is unacceptable.

As the largest State Sponsor of Terrorism, Iran – who has exported its revolution to Assad in Syria, the Houthis in Yemen, Hezbollah in Lebanon, and directed and supported attacks against American troops in Iraq — will be flush with money, not only to invest in their domestic economy, but to further pursue their destabilizing, hegemonic goals in the region. If Iran can afford to destabilize the region with an economy staggering under sanctions and rocked by falling oil prices, what will Iran and the Quds Force do when they have a cash infusion of more than 20 percent of their GDP — the equivalent of an infusion of $3.4 trillion into our economy?

If there is a fear of war in the region, it is fueled by Iran and its proxies and exacerbated by an agreement that allows Iran to possess an industrial-sized nuclear program, and enough money in sanctions relief to continue to fund its hegemonic intentions throughout the region. Imagine how a country like the United Arab Emirates – sitting just miles away from Iran across the straits of Hormuz feels after they sign a civilian nuclear agreement with the U.S., considered to be the gold standard, to not enrich or reprocess uranium? What do our friends think when we give our enemies a pass while holding them to the gold standard? Who should they trust?

Which brings me to another major concern with the JCPOA, namely the issue of Iran coming clean about the possible military dimensions of its nuclear program. For well over a decade, the world has been concerned about the secret weaponization efforts Iran conducted at the military base called Parchin. The goal that we have long sought, along with the international community, is to know what Iran accomplished at Parchin — not necessarily to get Iran to declare culpability — but to determine how far along they were in their nuclear weaponization program so that we know what signatures to look for in the future.

David Albright, a physicist and former nuclear weapons inspector, and founder of the Institute for Science and International Security, has said, ‘Addressing the IAEA’s concerns about the military dimensions of Iran’s nuclear programs is fundamental to any long term agreement… an agreement that sidesteps the military issues would risk being unverifiable.’ The reason he says that ‘an agreement that sidesteps the military issues would be unverifiable,’ is because it makes a difference if you are 90 percent down the road in your weaponization efforts or only ten percent advanced. How far advanced Iran’s weaponizing abilities are has a significant impact on what Iran’s breakout time to an actual deliverable weapon will be.

In a report to the U.N. Security Council, by a panel of experts, established pursuant to U.N. Security Council Resolution 1929, the experts state The Islamic Republic of Iran possesses two variants of ballistic missiles that, according to experts, are believed to be potentially capable of delivering nuclear weapons. One, the Ghada missile, is a variant of liquid-fuel Shahab-3, with a range of approximately 1,600km. The other is the solid-fuel Sejil missile, with a range of about 2,000km. To put that in perspective, the Ghada missile has a 650 mile range which puts Afghanistan, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Cyprus, Georgia, India, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Kazakhstan, Kuwait, Kyrgyzstan, Oman, Pakistan, Qatar, Russia, Saudi Arabia, and Syria, Tajikistan, Turkey, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, the United Arab Emirates, Uzbekistan, and Yemen in their sites.

The Sejil missile has a 1,250 mile rage which includes Albania, Belarus, Bulgaria, China, Djibouti, Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Greece, Hungary, Kosovo, Libya, Macedonia, Moldova, Nepal, Romania, Serbia, Somalia, and Sudan.

With so much at stake, the IAEA — after waiting over ten years to inspect Parchin, speak to Iranian nuclear scientists, and review additional materials and documents — are now told they will not have direct access to Parchin. The list of scientists the P5+1 wanted the IAEA to interview were rejected outright by Iran, and they are now given three months to do all of their review and analysis before they must deliver a report in December of this year. How the inspections and soil and other samples are to be collected are outlined in two secret agreements that the U.S. Congress is not privy to. The answer as to why we cannot see those documents, is because they have a confidentiality agreement between the IAEA and Iran, which they say ‘is customary,’ but this issue is anything but customary.

If Iran can violate its obligations for more than a decade, it can’t then be allowed to avail themselves of the same provisions and protections they violated in the first place. We have to ask: Why would our negotiators decide to negotiate access to other IAEA documents, but not these documents? Maybe the reason, as some members of Congress and public reports have raised, is because it will be the Iranians and not the IAEA performing the tests and providing the samples to be analyzed, which would be the equivalent of having an athlete accused of using performance enhancing drugs submit an unsupervised urine sample to the appropriate authority. Chain of custody doesn’t matter when the evidence given to you is prepared by the perpetrator.

So in five months, we seek to resolve a major issue that has taken the better part of a decade to have access to, and with a highly questionable inspection regime as a solution. And, according to an AP story of August 14th – and I quote:

‘They say the agency will be able to report in December. But that assessment is unlikely to be unequivocal because chances are slim that Iran will present all the evidence the agency wants, or give it the total freedom of movement it needs to follow-up the allegations. Still, the report is expected to be approved by the IAEA’s board, which includes the United States and other powerful nations that negotiated the July 14 agreement. They do not want to upend their July 14 deal, and will see the December report as closing the books on the issue.’

It would seem to me that what we are doing is sweeping this critical issue under the rug.

Secretary Kerry has said that, ‘We have absolute knowledge with respect to the certain military activities they were engaged in,’ yet, for years we have insisted on getting access to Parchin and acquiring the knowledge we need to know.

General Hayden, the former CIA Director, said, ‘I’d like to see the DNI or any intelligence office repeat that for me. They won’t. What he is saying is that we don’t care how far they’ve gotten with weaponization. We’re betting the farm on our ability to limit the production of fissile material.’ Now, if they want to make that bet, they can, but the Administration should level with us and not insist revelations of PMD are unimportant. Instead General Hayden says, ‘he’s pretending we have perfect knowledge about something that was an incredibly tough intelligence target while I was director and I see nothing that has made it any easier.’

For me, the administration’s willingness to forgo a critical element of Iran’s weaponization — past and present — is inexplicable. Our willingness to accept this process on Parchin is only exacerbated by the inability to obtain anytime, anywhere inspections, which the Administration always held out as one of those essential elements we would insist on and could rely on in any deal. Instead, we have a dispute resolution mechanism that shifts the burden of proof to the U.S. and its partners, to provide sensitive intelligence, possibly revealing our sources and the methods by which we collected the information and allow the Iranians to delay access for nearly a month, a delay that would allow them to remove evidence of a violation, particularly when it comes to centrifuge research-and-development, and weaponization efforts that can be easily hidden and would leave little or no signatures.

The Administration suggests that — other than Iraq — no country was subjected to anytime, anywhere inspections. But Iran’s defiance of the world’s position, as recognized in a series of U.N. Security Council Resolutions, does not make it ‘any other country.’ It is their violations of the NPT and the Security Council Resolutions that created the necessity for a unique regime and for anytime, anywhere inspections.

Mark Dubowitz, the widely-respected sanctions expert from the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, has said:

‘For Secretary Kerry to claim we have absolute knowledge of Iran’s weaponization activities is to assume a level of U.S. intelligence capability that defies historical experience. That’s why he, President Obama, Undersecretary Sherman and IAEA chief Amano all have made PMD resolution such an essential condition of any nuclear deal.’

He goes on to say:

‘The U.S. track record in detecting and stopping countries from going nuclear should make Kerry more modest in his claims and assumptions. The U.S. missed the Soviet Union, China, India, Pakistan, Israel and North Korea. Washington underestimated Saddam’s program in 1990. Then it overestimated his program in 2003 and went to war to stop a nonexistent WMD program.’

It is precisely because of this track record that permitting Iran to have the size and scope of an industrialized nuclear program, permitted under the JCPOA is one of the great flaws of the agreement.

If what President Obama’s statement, in his NPR interview of April 7th, 2015, that ‘a more relevant fear would be that in year 13, 14, 15 they have advanced centrifuges that enrich uranium fairly rapidly, and at that point breakout times would have shrunk almost down to zero’ – is true, then it seems to me that — in essence — this deal does nothing more than kick today’s problem down the road for ten-15 years, and, at the same time, undermines the arguments and evidence we’ll need, because of the dual-use nature of their program, to convince the Security Council and the international community to take action.

President Obama continues to erroneously say that this agreement permanently stops Iran from having a nuclear bomb. Let’s be clear, what the agreement does is to recommit Iran not to pursue a nuclear bomb, a promise they have already violated in the past. It recommits them to the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT), an agreement they have already violated in the past. It commits them to a new Security Council Resolution outlining their obligations, but they have violated those in the past as well.

So the suggestion of permanence, in this case, is only possible for so long as Iran complies and performs according to the agreement because the bottom line is that this agreement leaves Iran with the core element of a robust nuclear infrastructure.

The fact is — success is not a question of Iran’s conforming and performing according to the agreement. If that was all that was needed – if Iran had abided by its commitments all along — we wouldn’t be faced with this challenge now. The test of success must be — if Iran violates the agreement and attempts to break-out — how well we will be positioned to deal with Iran — at that point. Trying to reassemble the sanctions regime, including the time to give countries and companies notice of sanctionable activity, which had been permissible up to then, would take-up most of the breakout time, assuming we could even get compliance after significant national and private investments had taken place. That indeed would be a ‘fantasy.’

So the suggestion of ‘permanency’ in stopping Iran from obtaining a nuclear weapon depends on ‘performance.’ Based on the long history of Iran’s broken promises, defiance and violations, that is hopeful. Significant dismantlement, however, would establish ‘performance,’ and therefore the threat of the capability to develop a nuclear weapon would truly be permanent, and any attempt to rebuild that infrastructure would give the world far more time than one year.

The President and Secretary Kerry have repeatedly said that the choice is between this agreement or war. I reject that proposition, as have most witnesses, including past and present Administration members involved in the Iran nuclear issue, who have testified before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and who support the deal but reject the binary choice between the agreement or war.

If the P5+1 had not achieved an agreement, would we be at war with Iran? I don’t believe that.

For all those who have said they have not heard — from anyone who opposes the Agreement – a better solution, they’re wrong. I believe there is a pathway to a better deal.

Advocates of the deal argue that a good deal that would have dismantled critical elements of Iran’s nuclear infrastructure isn’t attainable – that the Iranians were tough negotiators — and that despite our massive economic leverage and the weight of the international community we couldn’t buy more than 10 years of inspection and verification in exchange for permanent sanctions relief, and for revoking Iran’s pariah status. I don’t believe that.

It is difficult to believe that the world’s greatest powers, the U.S., Great Britain, France, Russia, China, Germany and the European Union, sitting on one side of the table, and Iran sitting alone on the other side, staggering from sanctions and rocked by plummeting oil prices, could not have achieved some level of critical dismantlement.

I believe we should have insisted on meeting the requirements we know are necessary to stop Iran from getting a nuclear weapon today and in ten years, or we should have been prepared to walk away.

I believe we could still get a better deal and here’s how: We can disapprove this agreement, without rejecting the entire agreement.

We should direct the Administration to re-negotiate by authorizing the continuation of negotiations and the Joint Plan of Action – including Iran’s $700 million-a-month lifeline, which to date have accrued to Iran’s benefit to the tune of $10 billion, and pausing further reductions of purchases of Iranian oil and other sanctions pursuant to the original JPOA. I’m even willing to consider authorizing a sweetener – a one-time release of a predetermined amount of funds – as a good faith down payment on the negotiations.

We can provide specific parameters for the Administration to guide their continued negotiations and ensure that a new agreement does not run afoul of Congress. A continuation of talks would allow the re-consideration of just a few, but a critical few issues, including:

First, the immediate ratification by Iran of the Additional Protocol to ensure that we have a permanent international arrangement with Iran for access to suspect sites.

Second, a ban on centrifuge R&D for the duration of the agreement to ensure that Iran won’t have the capacity to quickly breakout, just as the U.N. Security Council Resolution and sanctions snapback is off the table.

Third, close the Fordow enrichment facility. The sole purpose of Fordow was to harden Iran’s nuclear program to a military attack. We need to close the facility and foreclose Iran’s future ability to use this facility. If Iran has nothing to hide they shouldn’t need to put it under a mountain.

Fourth, the full resolution of the ‘possible military dimensions’ of Iran’s program. We need an arrangement that isn’t set up to whitewash this issue. Iran and the IAEA must resolve the issue before permanent sanctions relief, and failure of Iran to cooperate with a comprehensive review should result in automatic sanctions snapback.

Fifth, extend the duration of the agreement. One of the single most concerning elements of the deal is its 10-15 year sunset of restrictions on Iran’s program, with off ramps starting after year eight. We were promised an agreement of significant duration and we got less than half of what we are looking for. Iran should have to comply for as long as they deceived the world’s position, so at least 20 years.

And sixth, we need agreement now about what penalties will be collectively imposed by the P5+1 for Iranian violations, both small and midsized, as well as a clear statement as to the so-called grandfather clause in paragraph 37 of the JCPOA, to ensure that the U.S. position about not shielding contracts entered into legally upon re-imposition of sanctions is shared by our allies.

At the same time we should: Extend the authorization of the Iran Sanctions Act which expires in 2016 to ensure that we have an effective snapback option; Consider licensing the strategic export of American oil to allied countries struggling with supply because Iranian oil remains off the market; Immediately implement the security measures offered to our partners in the Gulf Summit at Camp David, while preserving Israel’s qualitative military edge.

The President should unequivocally affirm and Congress should formally endorse a Declaration of U.S. Policy that we will use all means necessary to prevent Iran from producing enough enriched uranium for a nuclear bomb, as well as building or buying one, both during and after any agreement. We should authorize now the means for Israel to address the Iranian threat on their own in the event that Iran accelerates its program and to counter Iranian perceptions that our own threat to use force is not credible. And we should make it absolutely clear that we want a deal, but we want the right deal — and that a deal that does nothing more than delay the inevitable isn’t a deal we will make.

We must send a message to Iran that neither their regional behavior nor nuclear ambitions are permissible. If we push back regionally, they will be less likely to test the limits of our tolerance towards any violation of a nuclear agreement.

The agreement that has been reached failed to achieve the one thing it set out to achieve – it failed to stop Iran from becoming a nuclear weapons state at a time of its choosing. In fact, it authorizes and supports the very road map Iran will need to arrive at its target.

I know that the Administration will say that our P5+1 partners will not follow us, that the sanctions regime will collapse and that they will allow Iran to proceed, as if they weren’t worried about Iran crossing the nuclear- weapons capability threshold. I heard similar arguments from Secretary Kerry, when he was Chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee, as well as Assistant Secretary of State Wendy Sherman, Assistant Secretary of Treasury David Cohen and others, when I was leading the charge to impose new sanctions on Iran.

That didn’t happen then and I don’t believe it will happen now. Despite what some of our P5+1 Ambassadors have said in trying to rally support for the agreement, and echoing the Administration’s admonition, that it is a take it or leave it proposition, our P5+1 partners will still be worried about Iran’s nuclear weapon desires and the capability to achieve it. They, and the businesses from their countries, and elsewhere, will truly care more about their ability to do business in a U.S. economy of $17 trillion than an Iranian economy of $415 billion. The importance of that economic relationship is palpable as we negotiate TTIP, the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership agreement.

At this juncture it is important to note that, over history, Congress has rejected outright or demanded changes to more than 200 treaties and international agreements, including 80 that were multilateral.

Whether or not the supporters of the agreement admit it, this deal is based on ‘hope’– hope that when the nuclear sunset clause expires Iran will have succumbed to the benefits of commerce and global integration. Hope that the hardliners will have lost their power and the revolution will end its hegemonic goals. And hope that the regime will allow the Iranian people to decide their fate.

Hope is part of human nature, but unfortunately it is not a national security strategy.

The Iranian regime, led by the Ayatollah, wants above all to preserve the regime and its Revolution, unlike the Green Revolution of 2009. So it stretches incredulity to believe they signed on to a deal that would in any way weaken the regime or threaten the goals of the Revolution.

I understand that this deal represents a trade-off, a hope that things may be different in Iran in ten-15 years. Maybe Iran will desist from its nuclear ambitions. Maybe they’ll stop exporting and supporting terrorism. Maybe they’ll stop holding innocent Americans hostage. Maybe they’ll stop burning American flags. And maybe their leadership will stop chanting, “Death to America” in the streets of Tehran. Or maybe they won’t.

I know that, in many respects, it would be far easier to support this deal, as it would have been to vote for the war in Iraq at the time. But I didn’t choose the easier path then, and I’m not going to now. I know that the editorial pages that support the agreement would be far kinder, if I voted yes, but they largely also supported the agreement that brought us a nuclear North Korea.

At moments like this, I am reminded of the passage in John F. Kennedy’s book, ‘Profile in Courage,’ where he wrote:

‘The true democracy, living and growing and inspiring, puts its faith in the people – faith that the people will not simply elect men who will represent their views ably and faithfully, but will also elect men (and I would parenthetically add woman) who will exercise their conscientious judgment – faith that the people will not condemn those whose devotion to principle leads them to unpopular courses, but will reward courage, respect honor, and ultimately recognize right.’

He said:

‘In whatever arena in life one may meet the challenges of courage, whatever may be the sacrifices he faces if he follows his conscience – the loss of his friends, his fortune, his contentment, even the esteem of his fellow men – each man must decide for himself the course he will follow. The stories of past courage can define that ingredient – they can teach, they can offer hope, they can provide inspiration. But they cannot supply courage itself. For this each man must look into his own soul.’

I have looked into my own soul and my devotion to principle may once again lead me to an unpopular course, but if Iran is to acquire a nuclear bomb, it will not have my name on it.

It is for these reasons that I will vote to disapprove the agreement and, if called upon, would vote to override a veto.

Thank you. May God Bless these United States of America.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.