The principles of Andrew Jackson and the Jacksonians are becoming the heart of the Republican Party and reflect its future in American politics. Though rarely regarded as part of the pantheon of conservative heroes, Jackson was the figurehead of a unique set of ideas that can and should be embraced by the Grand Old Party.

Progressive attitudes toward America’s seventh president have had an incredible turnaround in the last half-century. Since the days of liberal historian Arthur Schlesinger’s incredibly influential The Age of Jackson, progressives have attempted to link Jacksonian ideas to Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal. Generally peddling the idea that Jackson—like FDR—stood up to conservative “plutocrats” of the business community, liberals attempted to link their intellectual lineage to Thomas Jefferson and Old Hickory.

Though Schlesinger’s book was engaging and well-written, his analysis was wildly inaccurate. New York Magazine’s Jonathan Chait has recognized the fallacy of Jackson’s connection to modern progressivism in his recent article “The Party of Andrew Jackson vs. the Party of Obama.” Chait writes of Schlesinger’s myth making: “His analysis created a kind of official party history, in which Thomas Jefferson and Andrew Jackson led inevitably to the triumph of the dominant figure of Schlesinger’s day, Franklin Roosevelt.” Democrats continue to hold “Jefferson-Jackson Day” dinners to honor the mistaken “fathers” of their party, but as Chait correctly notes, “Downplaying or ignoring Jackson’s conservatism, while conjuring a liberal ideology on his behalf, served a partisan interest for 20th-century Democrats.”

After attacking and dismissing Jacksonian ideas as essentially racist, genocidal, pro-slavery, ignorant, and corrupt, Chait writes that the connection between Jackson and conservatism is “real” and unflatteringly concludes that “Jackson’s increasingly dismal historical reputation tracks the inevitable collapse of his vestigial partisan tradition. Modern Democrats increasingly look upon Jackson with revulsion, and if he could return to see what his party has become, he would reciprocate.”

Jackson likely would have been disgusted by the modern Democrat Party. However, Chait’s attacks on Jackson and Jacksonian principles are nothing but shallow slanders on a badly-distorted intellectual and political heritage.

Jacksonian Federalism: A Balance of Power

The most obvious difference between Jacksonians and progressives is that Jackson and his followers opposed centralized government power, preferring strict interpretations of the constitution. The Jacksonians, following in the political footsteps of Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, attempted to decentralize power by pushing control over policy back to the states. Though some mistakenly claim that Jackson was “big government” because he expanded the power of the executive, this is a deep misunderstanding. Jackson ferociously resisted attempts by the legislature to dole out pork projects to their constituencies, which had become all too common in the 1820s and 1830s. He wielded his executive authority to prevent expansion of the federal government, issuing a record number of vetoes.

For instance, Jackson issued the Maysville Road veto, halting an infrastructure scheme mostly located in Kentucky, because he thought Americans were “losing sight of the distinctions” between policies of a “national and local character.” Jackson and his followers argued most day-to-day policies should be left to the states.

Jackson strongly adhered to federalism and decentralization, but also that this system was buttressed and strengthened by an indivisible union of states. He believed that federalism was vital to protecting individual rights. Jackson wrote in a veto message, “It was not for territory or state power that our Revolutionary fathers took up arms; it was for individual liberty and the right of self-government.”

Jacksonian Capitalism: Competition for All, Special Favors for None

Another critical misunderstanding of the Jacksonians is the belief that they were anti-capitalist and “agrarian” because they opposed “monopolies” and warred against the national Second Bank of the United States. In many ways the Jackonians were the complete reverse, rebelling against the more state-guided capitalism of the old Federalists and Whigs. The Jacksonians were anti-crony capitalist and specifically hated state-supported monopolies. The Jacksonian philosophy was all about competition and laissez-faire capitalism.

Jackson’s message regarding the veto of the Second Bank of the United States charter is one the most eloquent attacks on crony capitalism ever given. In the speech he said:

Equality of talents, of education, or of wealth can not be produced by human institutions. In the full enjoyment of the gifts of Heaven and the fruits of superior industry, economy, and virtue, every man is equally entitled to protection by law; but when the laws undertake to add to these natural and just advantages artificial distinctions, to grant titles, gratuities, and exclusive privileges, to make the rich richer and the potent more powerful, the humble members of society-the farmers, mechanics, and laborers-who have neither the time nor the means of securing like favors to themselves, have a right to complain of the injustice of their Government.

This statement could not be more different than FDR’s “Second Bill of Rights” in which citizens had a right to demand equality and “exclusive privileges.”

The prolific and shamefully-forgotten Jacksonian essayist William Leggett continually assailed corrupt connections between big business and big government, extolling the virtues of equality of opportunity and free competition. Citing Jackson’s bank veto, Leggett wrote in 1834, “Governments have no right to interfere with the pursuits of individuals, as guaranteed by those general laws, by offering encouragements and granting privileges to any particular class of industry.”

The Jacksonian, anti-crony capitalism message is clearly important to modern conservatives, especially those who identify with the Tea Party. The base of the party has rebelled against the bipartisan TARP bailouts, the massive stimulus program, and recently achieved a monumental success, goading Congress to eliminate the Ex-IM Bank.

Jacksonian Republicanism: Anyone Can Become an American

Another Jacksonian principle is the idea of “republicanism,” as opposed to ethnic nationalism. Jacksonian Democrat and famous writer James Fenimore Cooper wrote a number of fiction books, such as The Last of the Mohicans, which described the Americanizing influences of the New World and the frontier. Unlike progressive historian Frederick Jackson Turner’s extolling the “white man with Indian characteristics,” Cooper described the frontier as a place anyone, regardless of race, could become an American.

Editors Bradley J. Birzer and John Willson wrote in the introduction to James Fenimore Cooper: The American Democrat, “The American is not a white man with Indian characteristics. Instead, the frontier can make anyone—regardless of background or sex—a true American, noble, liberty-loving, and virtuous. Ultimately, then, one cannot base ‘Americanness’ on racial or ethnic background or terms. Instead, Americanness is individual and cultural; it is based on virtue and merit.”

An example of Jacksonian ideas in modern conservatism is the Goldwater Institute’s recently-filed case to end American Indian adoption restrictions. Currently, the law restricts the adoption of Native American children by non-Native Americans, even when the children are in abusive situations.

Jacksonian republicanism binds the country through patriotism rather than ethnic solidarity and socialism. The American people are neither the masses nor classes, but individuals with equal rights.

This kind of color-blind Americanness, however, is anathema to modern liberals like Chait, who misrepresent Jacksonians as racists hiding behind an agenda of inequality and pretend “racial innocence.”

The Left Attacks the Jacksonian Revival by Misrepresenting Jackson’s Record

It should be quite obvious that Jacksonian principles are diametrically opposed to those of modern progressivism. As always with the left, the previous generation’s heroes must be dragged through the mud and tarnished now that the ideological connection is severed.

Following a line of attack that has recently been made in historian Steve Inskeep’s new book Jacksonland, Chait claims that Jackson removed the Cherokee and other tribal people from their land to personally enrich himself and his friends. Chait writes, “Jackson and his cronies personally grew rich from the policy of land expropriation that formed the core of his agenda.”

While Inskeep fortunately avoids calling Jackson “genocidal” as many other commentators have done, he makes an almost equally damning charge that Jackson enriched himself at the expense of the county. This is a distortion and a vast simplification of American and tribal relations in the early 19th century.

A more thorough defense of Jackson and his presidential policy of Cherokee and general Indian removal can be read here and here. Jackson did not hate tribal people even if he hated tribal government, and even adopted a Creek Indian son whom he tried to have sent to West Point.

It is also absurd to say that Jackson’s policies were simply conducted for his own personal interest. Jackson purchased some land acquired from his treaties with Indians, but it was perfectly in line with his personal belief that the lands in the southwest had to be populated and developed for the good of the country’s national defense and the economy. He was simply fulfilling the promise of Thomas Jefferson’s Louisiana Purchase.

The editors of The Papers of Andrew Jackson wrote, “In doing all he could to prod the government toward a rapid sale of the lands in what became Alabama, Jackson pursued the interests of both the nation and his friends and neighbors in Tennessee,” they continued. “The surviving evidence shows that Jackson was highly interested in the development of Alabama and that he was at least a minor participant in the land boom in which many of his colleagues were deeply involved, but little more.”

Chait then makes another inaccurate claim that Jackson had a “notable passion for the institution of slavery.” Though Jackson did own slaves, he had no particular zeal for it. Chait demonstrates Jackson’s supposedly pro-slavery proclivities by referencing the Jackson administration’s decision to prevent abolitionist tracts from going through the mail because of the fear of provoking a slave uprising. The evidence Chait uses to demonstrate Jackson’s pro-slavery proclivities is his administration’s shut down of abolitionists tracts to the South that were provoking mob violence. Jackson was told about this crisis by postmaster general Amos Kendall, and gave his approval for allowing Southern offices to refuse delivering the abolitionist mail. Jackson remarked to Amos Kendall, his postmaster general, that he “regret[ted] such men [could] be guilty of the attempt to stir up amongst the South the horrors of servile war.”

The policy was a bad one, and even provoked criticism by many of his supporters, who rightly called it an abridgment of free speech. In fact, the aforementioned and strongly anti-slavery William Leggett attacked the decision, arguing that it demonstrated the need to privatize the Post Office!

However, Jackson’s policy did not demonstrate pro-slavery attitudes as much as it highlighted his strong law and order beliefs. This could be seen most dramatically during the Nullification Crisis in which Southerners tried to “nullify” federal tariff laws. Jackson was generally for free trade and opposed tariffs, but he saw this action as a pretext for anarchic secession, and ultimately as a cover to defend the institution of slavery.

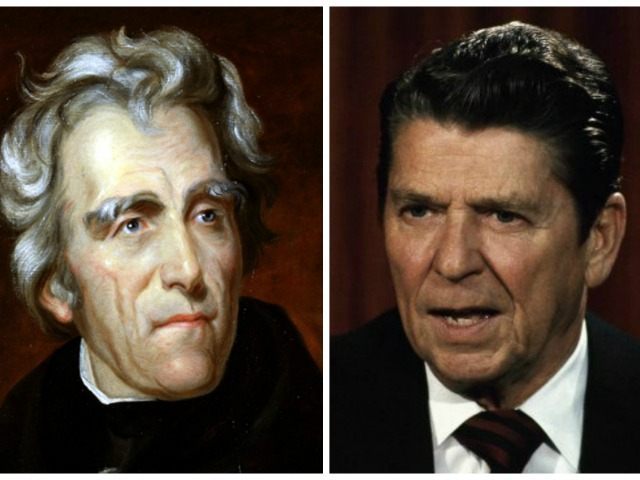

After issuing a dramatic proclamation on nullification—which would later be cited by Abraham Lincoln—and defending the one and indivisible union, Jackson threatened to invade his native South Carolina and hang the nullifiers. Jackson made a toast at a dinner banquet with arch-nullifier John C. Calhoun in attendance, proclaiming, “Our Federal Union: it must be preserved.” Ronald Reagan, an heir to the Jacksonian heritage, once said, “They were only seven words, but they were among the most important any American has ever spoken.”

Jackson wrote prophetically: “The nullifiers of the south intend to blow up a storm on the slave question… This ought to be met, for be assured these men would do any act to destroy this union and form a southern confederacy bounded, north, by the Potomac river.”

Historian Richard B. Ellis wrote in The Union at Risk: Jacksonian Democracy, States’ Rights and the Nullification Crisis that it is an “oversimplification” to call the Jacksonians pro-slavery. “Basically, Jackson and his followers viewed slavery as an unfortunate institution that they had inherited from a previous generation, and that they expected to eventually die out,” Ellis wrote.

“Although the Jackson administration viewed the abolitionists as fanatics and was insensitive to the moral issues raised by the institution of slavery and indifferent to the impact on those who had been enslaved, it was also hostile to the proslavery types who wished to make the defense of slavery a major political issue,” Ellis concluded.

The Unionist effort in the Civil War owes a great and today often unheralded debt to Jackson. Though Abraham Lincoln politically opposed Jackson most of his life, he hung the Hero of New Orleans’ portrait in his office throughout the war.

Many Jacksonians, Southerners, and those who comprised Jacksonian culture, unfortunately embraced the decidedly pro-slavery views of John C. Calhoun, George C. Fitzhugh, and Henry Hughes in the years leading up to the Civil War, after Jackson’s death. These ideas, in many ways, continued to echo into the 19th and 20th centuries. However, many of these attacks on the individual rights tradition of the Declaration of Independence provided the intellectual seeds for the modern left, not the right. Progressivism and the New Deal enjoyed particular appeal in the South during the early 20th century, while traditional Jacksonian ideas about limited government and individual rights lay dormant.

Chait argued that there is no philosophical tradition “connecting Jackson to such figures as Franklin Roosevelt and Lyndon Johnson.” He’s right.

True Jacksonian principles were revived by men like Barry Goldwater and Ronald Reagan, and they have been a driving force in conservative politics since their resuscitation. School choice, privatization of government services, commitment to free-market capitalism in opposition to crony capitalism, and a host of other policies are in large part intertwined with the Jacksonian tradition. They are creating an economic resurgence in the South and will be a driving force behind conservative policy reform well into the future.

While the modern Republican Party has many influences, from Alexander Hamilton to Abraham Lincoln and more, it owes a great, and mostly unacknowledged philosophical debt to Andrew Jackson and the Jacksonians.

Follow Jarrett Stepman on Twitter:@JarrettStepman. Reach him directly at jstepman@breitbart.com.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.