The Confederate flag was once cheered by thousands of freed slaves.

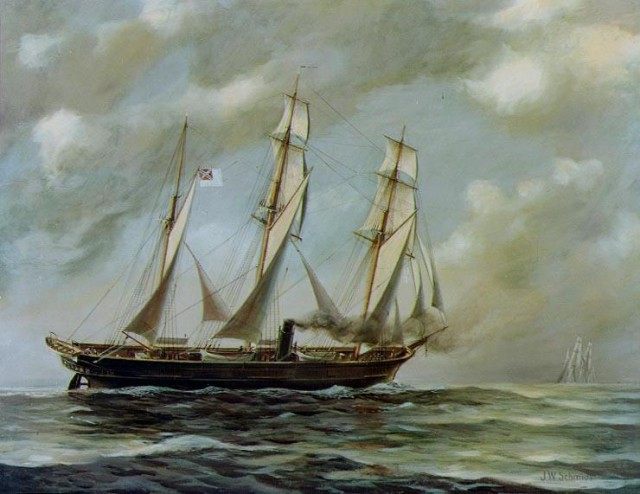

It happened in 1863, when the CSS Alabama caught a Union ship off the coast of Cape Town, South Africa. The spectacle was so thrilling to the locals, particularly the Malay and mixed-race (or “coloured”) population, that the naval battle was immortalized in a popular ditty.

To this day, Daar Kom Die Alabama (“Here Comes the Alabama“) is among the most beloved and frequently performed South African folk songs.

One reason was the sheer excitement of the event itself, which became associated with Cape maritime culture in general. (The middle of the song contains an unrelated verse about a brothel.)

Another reason for the lack of solidarity with American slaves was that in an era before telecommunications, black Americans were still largely unknown at the Cape, except as they were portrayed by traveling minstrels. (Blackface is still a feature of Cape folk music, as is the Islamic fez in the Ottoman style, as seen in the video above.)

But perhaps the most important reason was that Britain, which ruled the Cape, backed the Confederacy. And Britain had, 30 years before, abolished slavery in the Cape Colony. Thus pro-British sentiment transferred to Confederate sympathy.

If that sounds odd, consider that on Easter 2007, the late Rev. Peter J. Gomes–gay, black, and Republican–stunned his Harvard University congregation by declaring that he would have backed the British in the American Revolution, to win his freedom.

History is full of such complex oddities. The fact that the Confederate flag evoked liberation for freed slaves on the other side of the world does not outweigh the fact that it evoked slavery in the South itself, and that it has often been used since as a symbol of racism.

But that is not all the flag has meant. In liberal terms: casting the flag as a matter of simple evil is rather like gentrifying a neighborhood, paving over a dilapidated but eccentric landscape in favor of something more manageable–but also sterile.

***

It is perhaps fitting that it should fall to Republicans to lead the sudden assault on Confederate symbols and history. It was Republicans who opposed slavery, who fought to defeat the Confederacy, and who attempted the abortive Reconstruction.

Democrats, in contrast, stood for states’ rights and slavery, and pushed back against the postwar order, enacting Jim Crow and fostering the Ku Klux Klan. The Republicans, now dominant across the South, are back to pick up where they left off.

But that is not the primary motivation for the changes.

Today’s Republican Party has, critics often note, inherited much of the Democratic Party’s former white constituency in the South. And while that support has boosted the party’s fortunes for several decades, today it is almost seen as a burden.

In removing the Confederate flag from the Capitol in South Carolina, and targeting Confederate symbols elsewhere, Republican leaders clearly hope to transcend their narrowing racial and regional base.

President Barack Obama is a factor, too, though he is “leading from behind” at best. It is remarkable how little he has contributed directly to the debate over the Confederate flag. His main focus, in the days since nine black congregants were murdered by a white racist at a church in Charleston, has been gun control and racism in general.

Even Hillary Clinton, the likely Democratic presidential nominee in 2016 and former First Lady of Arkansas, joined the debate only after Republicans had taken decisive action.

Obama has provoked Republicans, indirectly, to act by showing, in two successive elections, that the country’s new demographics might trump nearly every other factor.

A white candidate who had belonged to a racist hate church, as Obama did, could not have been elected in 2008. Nor could Obama have been re-elected in 2012, after the debacle of Obamacare and the wasteful stimulus, were it not for his targeting of minority voters.

Today, Republicans are seizing a rare opportunity to appeal to Obama’s America, too.

***

Yet the GOP is getting little credit in the media, while Democrats seem more excited about the capitulation of what remains of the Confederacy–as well they should be.

The focus on the Confederate flag confirms what the left and the media have claimed about the attack in Charleston–that it represented a broader pattern of prejudice in society as whole, one for which the political right is supposedly responsible. They know, too, that Republicans are prone to panic at accusations of bigotry.

More subtly, Democrats have also managed to dodge any reckoning with their party’s own past. It was Democrats who presided over segregation; it was Democrats who restored the Confederate flag to the South Carolina State House. In 1992, Bill Clinton featured the Confederate flag on some campaign materials; in 2008, some supporters of Hillary Clinton still did so, too. Without acknowledging or apologizing for that past, Mrs. Clinton now declares the flag off-limits.

Democrats now intend to press home their advantage. They are going to make an issue out of Confederate symbols and place names, wherever they may be found–in state flags, in statues, in street names, or on college campuses.

Republicans seem to think that if they act first, they can create a firebreak, preventing a political inferno like the “war on women” of 2012. But the GOP is just playing with matches; in the unfolding “war on history,” Democrats have the flamethrowers.

It is Democrats who have championed the new culture of offense, where perceived “microaggressions” lead to massive retaliation, costing reputations and careers.

And Democrats do not simply intend to erase history: they intend to revise and replace it with their own. Republicans who propose the removal of statues of Jefferson Davis and Robert E. Lee seem to have given little thought to what might replace them.

Be assured that Democrats will have a list of ideological heroes ready.

***

The nine victims in Charleston–none of whom has been buried, as of this writing–have already been eclipsed by politics. The Confederate flag was tangential, at best, to the attack itself: the murderer waved the flag in photos but said he acted precisely because Charleston was so indifferent to his racial obsessions.

Yet the horror became the catalyst for a rejection of Confederate symbols so far-reaching that even private retailers are refusing to sell Confederate-themed merchandise.

And there seems little resistance.

One reason is that the South has changed dramatically since 1999, when South Carolina reached a compromise and removed the flag from the Capitol dome itself to a war memorial on the State House grounds. The regional economy has grown rapidly, aided by Republican policies such as right-to-work laws and low taxes. With that growth has come an increasingly urbane population–including a migration of black families from the stagnant cities of the north.

The new South is also more diverse than it once was–and more integrated than many other parts of the country. It has become less rooted to its past, and more swept up in a national pop culture that has become ubiquitous in the Internet era, with social media and streaming television overtaking local news and regional culture.

The South is increasingly part of a national monoculture, where there are still minor inflections of difference, but regional identities are slowly wearing away.

The millennial generation is particularly disconnected from history. The mobile smartphone culture of “status updates” and Snapchat emphasizes the here and now. Books–a key link to the past–are disappearing from the lives of many.

The country’s political leadership talks about “fundamental transformation” in the future tense, and has little interest in the past–except to disparage it, and the South’s history in particular.

For many millennials, that past is an anvil, not an anchor.

***

And yet the culture of “microaggressions” did not start with, nor will it end with, complaints about Confederate symbols.

Recall that then-Senator Barack Obama once took issue with the American flag, saying that he would not wear a lapel pin featuring the Stars & Stripes because “true patriotism” meant being willing to criticize the country, not celebrating its symbols.

Republican leaders, by accepting a kind of collective guilt for Charleston, have set a precedent not easily undone.

Gov. Nikki Haley’s dignified speech at the South Carolina State House, in which she defended the Confederate flag as a symbol but called for its removal, had the feeling of a valediction. It was meant to give closure to a grieving state. It proposed a kind of compromise: the flag would be removed from state grounds, but tolerated on private property.

Yet Haley left unclear whether it would still be tolerated in other public spaces. That, to the left, became an open invitation.

Immediately, the pressure mounted on other governments–and on private retailers and manufacturers. Hillary Clinton declared: “It shouldn’t fly anywhere.”

As prices for Confederate flags skyrocketed, online vendors declared that they would no longer sell them, or even–as on eBay–permit their exchange. The company that makes Dukes of Hazzard toys announced that it was removing the flag from the “General Lee” car.

The private space that Haley seemed to allow narrowed rapidly.

At the same time, ironically, special exceptions to the new order began to emerge.

The media celebrated President Obama for using the “n-word” in a podcast interview with a comedian–perhaps the first time any president had been recorded using that word in public.

The Washington Post advertised a story about Republican presidential contender and Louisiana Governor Bobby Jindal with the teaser: “There’s not much Indian left in Bobby Jindal.”

Despite Haley, Republicans remain the enemy.

***

The passion for replacing symbols and removing statues is more familiar to post-conflict societies than the U.S.

In South Africa, the fight against old symbols has become a substitute for real progress, as the country’s new multiracial democracy bogs down in corruption and frustration.

This year, students demanded–and quickly won–the removal of a statue of Cecil John Rhodes at the University of Cape Town. Never mind the fact that he donated the land upon which the school still sits. Never mind that Nelson Mandela had joined the Rhodes Foundation in a gesture of reconciliation.

For the perpetually aggrieved, there is no reconciliation–only a pause before the fight continues.

It is the nature of failing governments to rail against symbols to cover up their own faults. Doing away with Confederate flags and place-names will do nothing to improve the lot of black Americans, which the left maintains is still a legacy of slavery and discrimination. In fact, the attack on symbols may give politicians an excuse to continue to neglect the needs of the black community.

There are, in fact, some old institutions in urgent need of dismantling: decrepit public schools, the entitlement system, the welfare state. The focus on Confederate symbols provides Democrats with a timely diversion.

Ultimately, the left’s goal is to remake the Constitution itself in a “social democratic” mould.

Obama said in his “n-word” interview that racism is part of the “DNA” of the country. If so, it cannot be removed by taking down a flag. The system itself must be transformed.

To that end, Hillary Clinton is campaigning on a promise to change the First Amendment, supposedly to remove big money from politics, but in reality to entrench Democrats’ power. The effort to erase Confederate symbols will support that push for constitutional transformation.

As the story of the CSS Alabama reminds us, life is richer and more complex than today’s news cycle.

Edmund Burke admonished the French revolutionaries: “Compute your gains: see what is got by those extravagant and presumptuous speculations which have taught your leaders to despise all their predecessors, and all their contemporaries, and even to despite themselves, until the moment in which they became truly despicable.”

There is value in old symbols, even hated ones. In expunging them from our sight and memory, we remove what guidance they might provide.

“We are slowly forgetting how to oppose something without seeking its utter destruction,” writes Mollie Hemingway.

Ironically, in the name of sensitivity, we may be undoing the foundations of tolerance–the promise implied by Lincoln’s Second Inaugural: “With Malice toward none, with charity for all.”

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.