The most explosive passage in Michael Oren’s new book on the frayed U.S.-Israel relationship is not about President Barack Obama’s repeated fights with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. Rather, it is about Obama himself.

Struggling to understand how Obama–who has genuine empathy for Israel, Oren says–could adopt policies and postures so hostile to the Jewish state, Oren turns to Obama’s first memoir, Dreams from My Father.

What he reads shocks him:

More alarming for me still were Obama’s attitudes towards America. Vainly, I scoured Dreams from My Father for some expression of reverence, even respect, for the country its author would someday lead. Instead, the book criticizes Americans for their capitalism and consumer culture, for despoiling their environment and maintaining antiquated power structures. Traveling abroad, they exhibited “ignorance and arrogance”–the very shortcomings the president’s critics assigned to him.

Speaking to Breitbart News last week, Oren recalled his impressions of Dreams. Obama said “nothing good about America” in his memoir, Oren says. Here was a man “without a word of praise or gratitude to America”–and yet “no one was listening” to what Obama truly believed.

“That said a lot to me about where America was” when Obama was elected, Oren recalls.

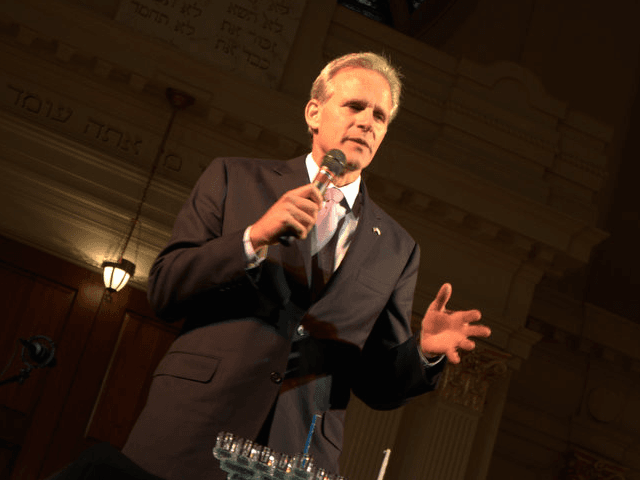

Oren, the American-born historian who served as Israel’s ambassador to the U.S. during President Obama’s first term, exposes shocking new details about the Obama administration’s treatment of Israel in his new book, Ally: My Journey Across the American-Israeli Divide.

Some of the episodes, such as Obama’s “snub” of Netanyahu during a 2010 visit to the White House, are well-known. Others are not, such as an encounter between Oren and then-UN Ambassador Susan Rice in New York, in which she threatened to drop support for Israel at the UN if the Netanyahu government did not “freeze all settlement activity”:

“If you don’t appreciate the fact that we defend you night and day, tell us,” Susan fumed, practically rapping her forehead. “We have other important things to do.”

Other clashes are more subtle, but no less jarring, such as Obama’s decision to ignore Israel’s role in earthquake relief in Haiti:

“Help continues to flow in, not just from the United States but from Brazil, Mexico, Canada, France, Colombia, and the Dominican Republic,” the president declared. Omitted from the list was Israel, the first state to arrive in Haiti and the first to reach the disaster fully prepared. I heard the president’s words and felt like I had been kicked in the chest.

On another occasion, the White House blackballed several guests from the ceremony at which Obama awarded Israeli President Shimon Peres the Presidential Medal of Freedom–because they happened to have criticized Obama on television.

Though polls indicate that mutual support between ordinary Americans and Israelis is at, or near, an all-time high, and defense cooperation remains close, tensions between the American and Israeli governments have seldom been worse.

Oren, who was an historian before becoming a diplomat and politician, is uniquely placed to offer an authoritative explanation, in exacting detail.

At times, Oren writes, Obama adopted a friendlier posture. “Yet, for every reaffirmation of the alliance, the administration took steps that disconcerted or even imperiled Israel,” he writes.

The root cause, Oren says, applying the historian’s analytical tools to his personal observations, was Obama’s approach to America itself–not to Israel.

Because Obama sees nothing special about America, its dominance in the world presents a moral problem for him. As president, Oren notes, Obama set out to solve that problem by courting America’s enemies and shunning its allies.

Obama is not anti-Israel, Oren argues, much less antisemitic, but his beliefs about America have meant a change in relations with Israel, a country deeply invested in America’s military–and moral–superiority.

These are not the ravings of a right-wing Likudnik.

Oren supported the disengagement from Gaza in 2005. He ran against Benjamin Netanyahu’s party in the recent Israeli elections. He spoke out against Netanyahu’s speech to Congress in March. And he once admired Barack Obama.

Yet Oren, who served as Israel’s ambassador from 2009 to 2013, builds a powerful argument that Obama is to blame for the stunning decline in U.S.-Israel relations.

It is a verdict heard increasingly from well-informed Democrats as the Obama administration nears its end. Former Harvard Law professor Alan Dershowitz, for example, a liberal Democrat and Hillary Clinton supporter who is still proud that he backed Obama, nevertheless has concluded that “the falling-out is almost exclusively the fault of Obama.”

In fact, Oren notes, fellow Democrats were mostly happy to back Obama’s policy.

At Oren’s first meeting with Jewish members of Congress, all of whom were Democrats (Republican Eric Cantor was absent), the party backed the president’s demand for a freeze on “settlement” construction, even in Jerusalem, which exceeded Palestinian demands and derailed peace talks.

And at one of Oren’s first meetings on Capitol Hill, he writes, Sen. Bill Nelson (D-FL) confronted him about “economic apartheid.” (Dan Mclaughlin, a spokesperson for Nelson, told Breitbart News that Nelson likely presented the letter as “just a courtesy,” not necessarily as an endorsement of its views.)

Even worse was the behavior of left-wing Jews–not only the radical activists of J Street, but opinion-makers like New York Times columnist Tom Friedman, who resorted to antisemitic stereotypes in reaching for metaphors to express their dislike of Netanyahu. (Congress had been “bought and paid for by the Israel lobby,” Friedman infamously wrote.)

Such examples of long-simmering left-wing hostility toward Israel emerged as Obama launched what Israelis regarded as an ill-informed “experiment” in U.S. foreign policy that failed to recognize the importance of steady American leadership abroad.

The president wanted to revolutionize relations with the Muslim world, boost cooperation with the UN, reach a nuclear deal with Iran, and create “daylight” between the U.S. and Israel, Oren explains.

The result was nearly incessant pressure on Israel.

Oren writes how Obama’s approach to Iran, for example, set the stage for clashes with Israel, which has no room for error in gauging Iran’s intentions.

Despite Obama’s repeated promises that the “military option” was “on the table,” Oren began to suspect otherwise, as did many Israelis. (It is perhaps no accident that Ally is to be released one week before the June 30 deadline for a nuclear deal with Iran.)

Oren writes, bitterly: “Most disturbing for me personally was the realization that our closest ally had entreated with our deadliest enemy on an existential issue without so much as informing us. Instead, Obama kept signaling his eagerness for a final treaty with Iran.”

Obama also erred in (belatedly) embracing the Arab Spring, Oren writes–a posture that Israeli officials described as “madness,” given the likely radical Islamist takeover. In demanding that then-Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak leave office “now,” Oren says, Obama undermined the value of the U.S. as an ally.

He adds: “That single act of betrayal–as Middle Easterners, even those opposed to Mubarak, saw it–contrasted jarringly with Obama’s earlier refusal to support the Green Revolution against the hostile regime in Iran.” Nevertheless, Oren observed the Obama staffers congratulating themselves for being on the “right side of history.” Admiring photos of Mubarak in the White House were soon taken down, he notes wryly.

The wild fluctuations in Obama’s foreign policy continued in Syria, where Hillary Clinton called dictator Bashar Assad a “reformer,” in spite of gruesome evidence to the contrary. Eager to appease Iran, the Obama administration quietly tried to keep Assad in power before flip-flopping. And even when Assad’s use of chemical weapons was obvious, Obama did not act on his own “red line.” A deal brokered with Russia to remove Syria’s chemical weapons–and first suggested by Israeli minister Yuval Steinitz, Oren reveals–barely helped Obama save face.

As for Obama’s team, Oren criticizes John Kerry’s well-meaning but oafish push for peace in 2013-4, which largely involved browbeating Israelis.

In addressing Hillary Clinton’s role, Oren is generous to a fault. Recalling the 45-minute lecture she delivered to Netanyahu during a 2010 spat over construction in Jerusalem (which the Obama administration calls “settlements”), Oren says that she did her duty reluctantly, reading from a script.

He told Breitbart News that Netanyahu actually maintained a personal friendship with her, calling Oren “every 15 minutes” to find out her condition after she suffered a fall in 2012.

In one instance, Oren demonstrably whitewashes Clinton’s record. He notes that at a forum on U.S-Israel relations in 2011, “a senior administration official warned that Israel was en route to becoming another Iran” in the area of woman’s rights. The “senior administration official” who made that outrageous statement was widely reported to be Hillary Clinton.

Clinton’s primary appeal in Oren’s eyes (and Netanyahu’s) seems to be that she is friendlier and more knowledgeable about Israel than Obama, even if not always an advocate for Israel in her own right.

Whether she wins or not in 2016, U.S. policy toward Israel may continue to be fraught with tension. Oren notes that Obama drew upon an emerging cohort of new policymakers steeped in resentment of American power and suspicion of the “Israel lobby.” They will linger in Washington long after Obama has left office.

Netanyahu, who correctly foresaw the challenge ahead, also saw the American-born Oren as the best hope for reaching out to a president who would treat Israel very differently from any before him.

Oren tried his best, he told Breitbart News, but could not stop all of the damage, despite his strenuous efforts.

The point he wishes to stress–a point he has made elsewhere recently–is that no Israeli government could have done better: Obama is the problem.

“Nobody has a monopoly over mistake-making,” Oren says, and acknowledges that Netanyahu made a few missteps. Still, he points out, when Netanyahu tried to give Obama what he wanted, his efforts were barely acknowledged.

For example, when Netanyahu gave a speech endorsing a Palestinian state in 2009–becoming the first Likud prime minister to do so–the White House ignored him. Instead, the pressure on Israel continued, causing the Palestinians to dig in and refuse to compromise.

Oren realized that he had to understand what motivated Obama–and why Americans had elected someone so at odds with its traditional worldview. In addition to reading Obama’s memoirs, Oren told Breitbart News, he consulted a New York Times coffee table book about Obama’s election–not because of the information it contained, but because of what it said about the media.

“If the paper of record is putting that out,” Oren told me, “that’s going to tell you a lot about the way the press is going to relate to this president.”

In Ally, he writes extensively about his battles with the Times, with CBS, and other outlets that give free rein to the most inflammatory criticisms of Israel and rarely allow for a fair, factual response.

Many of Obama’s most extraordinary policies, Oren contends, have been under-reported–such as Obama’s remark in 2010 that the U.S. is a military superpower, “whether we like it or not.”

Obama wants “to withdraw from the Middle East irrespective of the human price,” he observes. That abdication of American leadership, Oren believes, will have severe consequences for both Israel and the United States.

Ally is well-written, and entertaining in spite of its exhaustive detail–though Oren’s personal recollections of ambassadorial life are, at times, overly sentimental.

The autobiographical portions of the book, recalling Oren’s life as an Israeli paratrooper and an underground agent in the Soviet Union, are fascinating and inspiring. His account of the growing cultural divide between liberal American Jews and their brethren in Israel is both illuminating and alarming.

He has a unique perspective, as an Israeli who can explain the Jewish State from a near-native sabra perspective, yet in the idiom of his American audience. And he understands American politics with a depth few outsiders can match.

Throughout Ally, Oren draws on his skills as an historian to prove his case against Obama. He gives the president credit for great generosity towards Israel at times of need–whether helping to fund Iron Dome, urging Egypt to rescue Israeli diplomats from a rabid Cairo mob, or sending fire-fighting planes during a national emergency.

Yet he notes that “the Israel [Obama] cared about was also the Israel whose interests he understood better than its own citizens and better than the leaders they chose at the ballot box.”

Oren also points out the irony that Obama’s poor mistreatment of Israel often backfired by reinforcing Palestinian extremism.

Obama’s speech in Cairo in June 2009, he recalls, was “tactically, a killer” for the peace process, because it implied that Israel had no legitimacy other than as compensation for the Holocaust–reinforcing the Arab world’s rejection of Israel.

In the most recent war with Gaza, Oren notes, Obama hurt Israelis by describing their response to Hamas rocket attacks as “appalling,” even though Hamas deliberately put Palestinians in the line of fire. Later, Obama delayed arms shipments to Israel and even barred U.S. flights from landing at Ben-Gurion Airport as a punitive measure. “Hamas won its greatest-ever strategic victory,” Oren concludes. And Obama, via Jeffrey Goldberg, continued to deliver personal insults to Netanyahu.

Yet Oren did not write Ally to settle scores. Rather, he hopes that laying down the facts about the decline in U.S.-Israel relations will encourage both sides to pull back from the brink.

“I want everyone to stop! Stop this lunacy!” he exclaims.

He believes, passionately, that the U.S.-Israel alliance is not just essential for Israel’s success, but also for America’s security, and for the world in general.

He knows that the details of Obama’s missteps will gratify American conservatives, whose version of recent history is confirmed by his account–but he hopes liberals will listen, too.

Oren hopes to reach American Jews in particular. The community has a “core” that remains pro-Israel, he says, but has adopted social justice and tikkun olam (“fixing the world”) as the new basis of its civic identity.

He told Breitbart News that the 1960s socialist utopia for which Jewish liberals are nostalgic was “far less open, less democratic, less accepting than the Israel of today.”

In Ally, he describes his own “Israeli journey” with great care and skill. Oren told Breitbart News that he hopes his experiences will help a new generation of American Jews understand why he fell in love with Israel, and made it his own.

Perhaps they will embrace it, too. But above all, hard truths must be told.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.