If you thought that transgender was the ultimate manifestation of a society ever more unhooked from sanity, then you haven’t met the latest wave of “transabled” folk—healthy people who identify with the disabled and maim themselves to achieve their dream.

Unfortunately, this isn’t somebody’s sick joke. Where identity becomes relativized to the point that people are who they imagine and project themselves to be, everything is possible—and facilitated by an all-abetting culture.

Just ask “One Hand Jason,” a man who in 2008 intentionally cut off his right arm with a “very sharp power tool.” Having never quite accepted his arm as part of himself, “Jason” attempted different means of cutting and crushing the limb for months on end, training himself on first aid so he wouldn’t bleed to death, even practicing on animal parts sourced from a butcher.

When he finally succeeded, Jason “staged an accident,” letting everyone believe the loss of his arm was the result of a mishap.

“My goal was to get the job done with no hope of reconstruction or re-attachment, and I wanted some method that I could actually bring myself to do,” he said in an interview.

People like Jason have been classified as ‘‘transabled’’—believing that certain members of their bodies don’t truly belong to them, as if they had been born with a birth defect.

Alexandre Baril, a Quebec-born academic will present a paper on “transability” at this week’s Congress of the Social Sciences and Humanities at the University of Ottawa. Baril defines transability as “the desire or the need for a person identified as able-bodied by other people to transform his or her body to obtain a physical impairment.”

“The person could want to become deaf, blind, amputee, paraplegic. It’s a really, really strong desire,” he said.

Transability is a response to what psychologists are calling “body integrity identity disorder” (BIID), a psychological condition whereby “a person’s idea of how they should look does not match their actual physical form.” A common manifestation of the syndrome is a desire to have a specific body part amputated.

As bioethicist Wesley J. Smith wrote that when he first heard of BIID “the idea that cutting off healthy limbs would ever be considered a legitimate treatment option seemed ridiculous.”

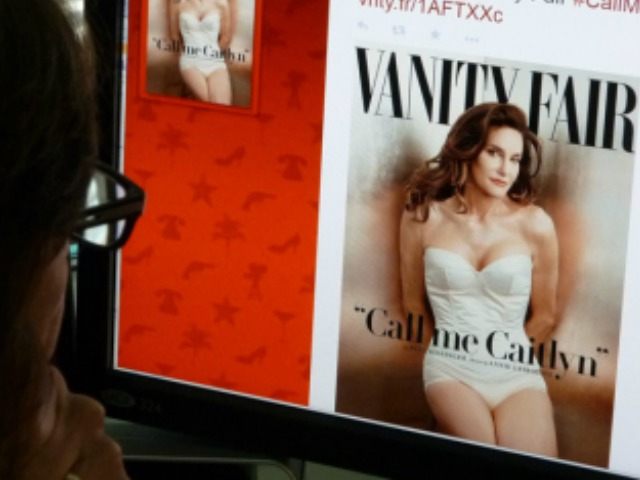

That seems to be no longer the case. As the Bruce Jenner case illustrates, self-definition “is becoming a fundamental right to which all must acquiesce and the medical arts must be applied to effectuate.”

Moreover, as history amply reveals, the choice to call a particular condition a “pathology” is ultimately a political and not a medical decision. Homosexuality was considered a mental illness by the American Psychiatric Association, until under intense pressure from gay rights activists it was declared “normal” in 1974. A movement is now afoot to remove gender dysphoria from the category of mental illnesses so that it will be just a condition, too. Why not BIID?

At the moment, BIID is not recognized in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Health Disorders (DSM-IV-TR), an index published by the American Psychiatric Association and regarded by most of the mental health community as the “bible of identified mental illnesses.”

But Dr. Michael First, a professor of clinical psychiatry at Columbia University, is working to change that. First has argued that there are pros and cons in “labeling something as a disorder.” According to First, “the disadvantage of labeling is stigma. We’re basically saying this is a mental illness—this is a sickness.”

Oddly—since gender reassignment seems to be an accepted “therapy” for transgender situations—some ethicists still insist that in the case of BIID “amputations would be contraindicated and must be evaluated as bodily injuries of mentally disordered patients.”

In a surprising show of common sense, some have suggested that rather than cut off body parts, we might try helping people accept themselves as they are.

“Instead of only curing the symptom, a causal therapy should be developed to integrate the alien limb into the body image,” wrote Sabine Müller in the American Journal of Bioethics.

Alas, this appeal to logic seems destined to fail.

When nature is removed from the equation the only thing left is personal self-expression, which can take on as many forms as there are human beings. Society’s pathological fear of offending others by calling a spade a spade and a sickness a sickness has left us in the impossible situation of supporting every whim imaginable, even to the point of amputating limbs, calling boys girls and helping people kill themselves.

“We can no longer appeal to absurdity in order to challenge our culture’s consistent conclusions,” it has been said, “because in a world we create, nothing is inherently absurd.”

Follow Thomas D. Williams on Twitter @tdwilliamsrome

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.