Shaking off a severe winter and West Coast port strike, the Labor Department is expected to report the economy added 220,000 jobs in May. That’s well below the 269,000 monthly average for 2104, and a strong dollar, revived productivity growth and shortage of qualified workers will slow jobs creation going forward.

First quarter GDP contracted 0.9 percent, and prospects for the balance of the year are for improved but hardly spectacular growth—averaging perhaps 2.5 percent.

Housing is picking up—existing home sales are scoring strong price gains and new home construction is making up for time lost to winter snows. However, traffic remains slow in new home showrooms, as first time buyers remain largely absent and builders focus on high end, older, and wealthier customers.

Manufacturing remains weak—and now more troubled. The strong dollar reduced exports, boosted imports, and subtracted 1.3 percentage points from growth in the first quarter. Its most significant negative effects on the price competitiveness of U.S. factories are yet to be felt.

Throughout the recovery, the administration has resisted suggestions from economists and pressures from congress to take substantive steps to remedy the overvalued dollar.

Now with Japan and South Korea explicitly targeting the dollar through their monetary policies and troubles brewing in China’s bubble economy, the burdens of an overvalued dollar will weigh even more heavily on U.S. manufacturers and exporters of services in information technology, media, and other intellectual property driven industries.

Over the last 40 years, productivity growth has fluctuated greatly but averaged about 2 percent a year. Recently, it has trended downward, scoring 1.6, 1.0, 0.9, and 0.7 percent for 2011 through 2014. And in both the fourth and first quarters, output per worker fell more than 2 percent.

The technological potential to improve labor productivity continues but simply has not been realized. Consequently, businesses have a lot of room to meet moderately growing demand with the workers already hired—and pressures to improve profitability and maintain stock valuations will compel those labor saving strategies.

As significantly, the supply of willing and able workers is dwindling.

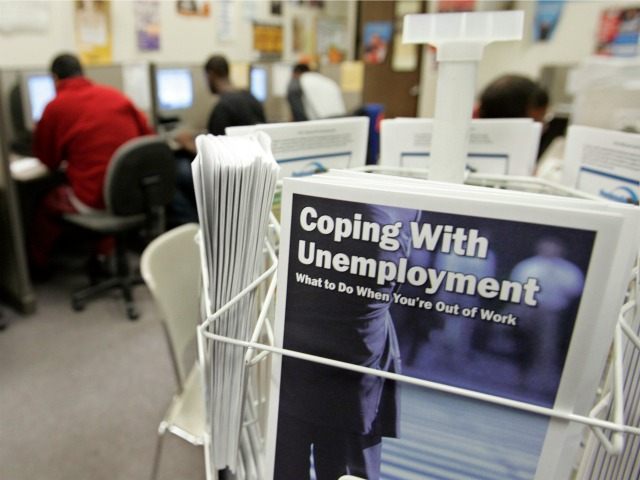

Scores of prime working age men displaced by construction and manufacturing meltdowns during the Great Recession have left the labor force permanently. Some 7 million men between the ages of 25 and 54 are neither working nor looking for work.

Nowadays, free and subsidized health care, food stamps, social security disability benefits, and the earned income tax credit for couples with one working spouse are all more easily available but phase down as household incomes rise. That greatly raises the opportunity cost of taking a job for many men.

Simply, we have gone from assisting the unemployed to paying for unemployment.

Hundreds of thousands of recent college graduates, thought to be underemployed, actually may be well placed as cab drivers and baristas. Many studied useless majors in college—businesses hardly need the thousands of international relations experts churned out by second-tier universities.

Even worse, many state universities and private colleges are besieged, thanks to the indiscriminate availability of student loans, by large numbers of emotionally and academically unsuitable students, and most recently by an influx of foreign students with fraudulent credentials.

Universities spending huge sums on mental health, social and remedial services cannot undo most of the consequences of poor childhood nutrition, incompetent parenting, and misspent youths. Consequently, about 40 percent of college graduates lack the basic skills associated with a college education—critical thinking and complex problem solving skills—posing embarrassing and yet unasked questions about the integrity of university presidents and their faculty.

Unless the economy endures a downward spiral in productivity, it will add many fewer jobs than policymakers anticipate. Without substantive policy responses to the overvalued dollar, compulsory work and training for idle men, and a downsizing and radical reform of higher education, things are simply not going to get better.

Peter Morici is an economist and business professor at the University of Maryland, and a national columnist. He tweets @pmorici1.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.