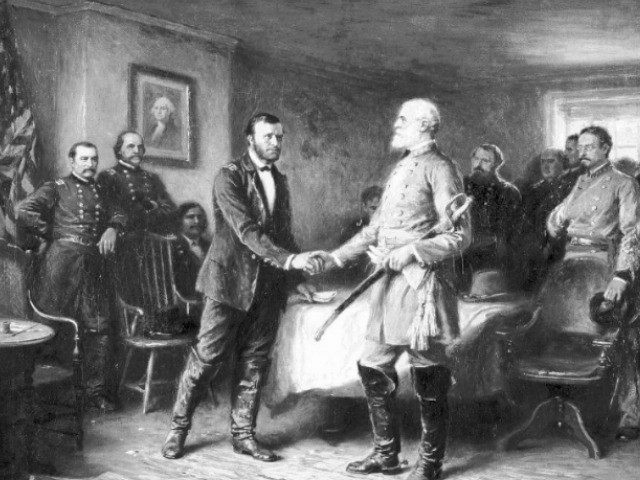

On this day, 150 years ago, Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered to Union General Ulysses S. Grant at the Appomattox, Virginia Courthouse. This event essentially ended the Civil War, the bloodiest conflict in American history, which claimed the lives of over 600,000 soldiers.

Though the surrender at Appomattox did not officially end the fighting, the collapse of the Army of Northern Virginia signaled that victory for the Confederate cause would be impossible. Led by General Lee for most of its existence, the Army of Northern Virginia had bottled up the Union Army of the Potomac for four years, winning a series of stunning battles that have become legendary: Second Manassas, Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, and numerous others.

However, after the incredible 1863 Union victory in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, Lee’s army had mostly been on the defensive, slowly succumbing to the better-armed and supplied Union forces. Once Ulysses Grant was given command in March of 1864, the primary Union army of the eastern theater had a general that could take it to ultimate victory.

In the waning days of 1865, Confederate arms were nearly spent. The once proud and dynamic Army of Northern Virginia had been reduced from about 100,000 men in 1862 to fewer than half of their initial ranks. Confederate soldiers were starving and under-supplied, missing many of their best commanders after losing them in battle, and without hope for reinforcements.

Lee’s Army was badly beaten at the Battle of the Five Forks in early April, which forced him to abandon his fortification at Petersburg, Virginia and leave a path open to the Confederate capitol city of Richmond.

In the last, desperate retreat through Virginia, the Confederate Army was in disarray and on the verge of collapse. After witnessing his army being badly thrashed at Sailor’s Creek, Lee cried out, “My God! Has the army been dissolved?”

In the final confrontation between the Army of the Potomac and Army of Northern Virginia near Appomattox Courthouse, it was clear that the Rebel army was indeed on the verge of being dissolved. Historian Bruce Catton wrote in The Army of the Potomac: Stillness at Appomattox about this last fight:

The blue lines grew longer and longer, and rank upon rank came into view, as if there was no end to them. A Federal officer remembered afterward that when he looked across the Rebel lines it almost seemed as if there were more battle flags than soldiers.So small were the Southern regiments that the flags were all clustered together, and he got the strange feeling that the ground where the Army of Northern Virginia had been brought to bay had somehow blossomed out with a great row of poppies and roses.

After receiving word of how badly his forces had been beaten by the Union army, Lee wrote a message to General James Longstreet, “There is nothing left for me to do but to go and see General Grant, and I would rather die a thousand deaths.”

After receiving news that Lee had surrendered, President Abraham Lincoln prepared and delivered what would be his final speech on April 11. He exclaimed from the White House balcony, “We meet this evening, not in sorrow, but in gladness of heart. The evacuation of Petersburg and Richmond, and the surrender of the principal insurgent army, give hope of a righteous and speedy peace whose joyous expression can not be restrained. In the midst of this, however, He from whom all blessings flow, must not be forgotten.”

Lincoln then called for a “national thanksgiving,” but said that the ultimate credit for victory belonged to the Union soldiers above anyone else. He said, “Their honors must not be parceled out with others. I myself was near the front, and had the high pleasure of transmitting much of the good news to you; but no part of the honor, for plan or execution, is mine. To Gen. Grant, his skillful officers, and brave men, all belongs.”

The final parade and surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia took place on April 12. General Joshua Chamberlain, hero of the Battle of Gettysburg, would receive the formal surrender on behalf of General Grant. Chamberlain recorded what he saw in his memoir; an account that historian Emory M. Thomas called the “best” description of the Confederate Army’s final act:

Before us in proud humiliation stood the embodiment of manhood: men whom neither toils and sufferings, nor the fact of death, nor disaster, nor hopelessness could bend from their resolve; standing before us now, thin, worn, and famished, but erect, and with eyes looking into ours, waking memories that bound us together as no other bond…

Instruction had been given; and when the head of each division column comes opposite our group, our bugle sounds the signal and instantly our whole line from left to right, regiment by regiment in succession, gives the soldiers salutation, from the “order arms” to the old “carry”—the marching salute. General [General John B.] at the head of the column, riding with heavy spirit and downcast face, catches the sound of shifting arms, looks up, and, taking the meaning, wheels superbly, making with himself and his horse one uplifted figure, with profound salutation as he drops the point of his sword to the boot toe; then facing to his own command, gives word for his successive brigades to pass us with the same position of the manual,—honor answering honor. On our part not a sound of trumpet, nor a roll of drum; not a cheer nor word, nor whisper of vainglorying, nor motion of man standing again at the order, but an awed stillness rather, a breathholding, as if it were the passing of the dead!

Though some Confederate leaders wanted to continue the war through guerrilla style fighting, Lee completely rejected this tactic. The war was over, the fighting hopeless, and the long road to recovery and rebuilding the country had to begin.

As Emory Thomas wrote in The Confederate Nation: 1861-1865, “Having sacrificed or been willing to sacrifice most of the ideological tenets they went to war to defend, ultimately Confederate Southerners were willing to lose their national life in order to save life itself.”

That the Union remains intact 150 years later, and that the United States ascended to almost incomparable power and prosperity in the 20th century is largely due to the efforts of Americans of the late 19th century, both Northern and Southern, who wished to see the country one and indivisible yet again.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.