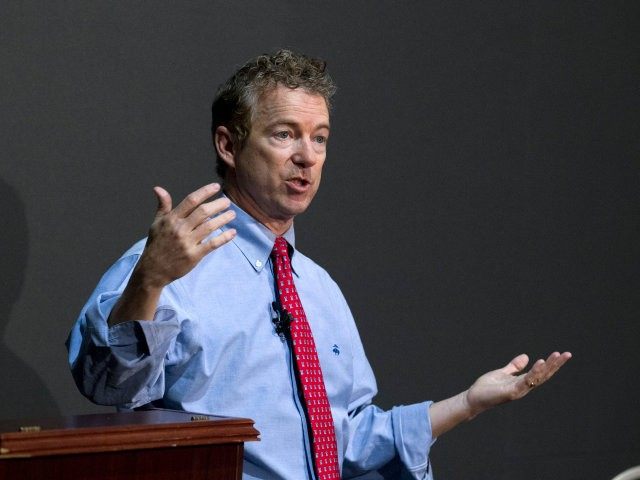

BOWIE, Maryland — Sen. Rand Paul (R-KY) was a hit speaker on the campus of Bowie State University on Friday, earning several rounds of applause and a standing ovation for the conservative message he delivered to a predominantly liberal audience at the historically black university—part of an outreach effort to traditionally non-Republican communities the senator and potential 2016 GOP presidential candidate has been engaged in nationwide for the five-plus years he’s been in the U.S. Senate.

Paul wove individual examples of people throughout history and in modern times who have faced unfair consequences as a result of government’s heavy hand, making his case to the room on the basis of the need to defend the full Bill of Rights in the Constitution—a classic Tea Party style of speech—all while citing the Founding Fathers, and making economic and social limited government conservative pitch that seemed to resonate throughout the theater inside the student center.

“Clyde Canard got out of prison the same month that I was born, which was a long time ago, in 1963,” Paul opened his speech with after a couple thank-yous to organizers. “The reason that Clyde Canard went to prison is that, his crime was he was trying to get enrolled in Mississippi Southern. At that time, it was very difficult for a black man or a woman to enroll. The second time he tried to enroll they planted liquor on him—he didn’t drink—and gave him a $600 fine. Can you imagine what $600 was like in 1963 if you were poor in Mississippi? One thing led to another and he declared bankruptcy. He tried to enroll a third time and he was arrested and bullied by police. But when he tried the third time, he’s declared bankruptcy and he goes by his farm to pick up some chicken feed—$25 worth of chicken feed—and you know what happens to him? He’s arrested, and you know what kind of prison term he’s given? Seven years in prison for stealing $25 worth of chicken feed which really was his—it was on his land which the bank was repossessing. People’s lives can spiral out of control from a $600 fine.”

Paul noted that “a lot of things have improved since” 1963, when this particular example happened—specifically the fact that the United States has gotten rid of segregation by law. However, he said, “we still have a problem in our country that’s a lot like segregation but it’s also like there are two systems.”

The major theme of Paul’s speech was a comparison back to the speech of Martin Luther King, Jr., in 1967, where the Civil Rights icon argued there are “two Americas.” Paul’s argument is due to the criminal justice system, the so-called “educational establishment” in Washington as he called it, and especially due to poverty and economic depravity in certain areas of the country, all symptoms of a larger problem that’s created by an out-of-touch political class that’s not interested in addressing the heart of the matter: there are Americans of all races and creeds who succeed in life and there are Americans of all races and creeds who don’t. And it’s unfair to those who don’t have a chance at success, he argued, because of a system that’s been created and abused by politicians.

“As Martin Luther King said in 1967, there are two Americas,” Paul said. “There’s one America that believes in life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. But there’s another America that is witness to a daily disgrace, a lack of hope, and despair. Why? Because like Clyde Canard, there are still people in our society who are being hounded by fines, hounded by this and that.”

What’s notable is that Paul talked about his time in Ferguson, Missouri, and in other black communities across America—but did not blame the police for the problems. In fact, he stood for the police as law enforcement officers just trying to do their jobs—and laid out how the government as a whole, and the politicians who run it, are the real source of the problems facing the second and less fortunate of the “two Americas” he spoke of.

“Several cities in Missouri, over a third of their budget is gotten by fines,” Paul said. “In Ferguson, there’s 21,000 people. Last year, there were 31,000 arrests. I tell people it isn’t just about what happened this year. It’s about this building up, it’s about this gradual increase. I call it an undercurrent of unease in our country. There still are two Americas. Most of the people here are part of the America that does believe and can believe in life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. Those who get a college education, those who get an education no matter the color of your skin, you are part of the America that can live the American dream. But there are many people who aren’t. So it’s a lack of education, but it’s also our criminal justice system. As I’ve learned more about the criminal justice system, I’ve come to believe it’s something that’s going to keep these two Americas separate.”

Paul continued by saying he specifically blames the politicians, not the police, for the problems.

“I don’t blame the police. I blame the politicians,” Paul said. “The politicians write these rules and we can change these rules at any minute. I’ve said I want to be part of changing some of these rules. I was at the White House last week and met with the president. Now, he and I don’t agree on a lot of stuff. But on criminal justice, we do.”

He said there is only a handful of lawmakers who agree with such changes.

“One of the laws that bothers me the most is something called civil forfeiture. Civil forfeiture is where the government can take your stuff whether they’ve convicted you of a crime or not. I think this turns justice on its head. I think that most of our judicial system, for those who believe in it, it’s that you are innocent until proven guilty.”

The audience at the historically black university erupted in applause for Paul.

“I want to reinforce in our judicial system that you are innocent until proven guilty. And the problem is with civil forfeiture, it’s the opposite,” Paul added before diving into several examples of people across America who he argues have been wrongly targeted by civil forfeitures.

One case he cited involved Christos Sourovelis, a Philadelphia man whose son was caught selling $40 worth of drugs off the back porch of his house. In response, the government seized his home—and the case caught national attention, which prompted the authorities to eventually abandon the home seizure under civil asset forfeiture because of the political pressure to do so.

“Their teenage son sold $40 worth of illegal drugs off the back porch,” Paul said. “The government took their house, evicted them and barricaded them. It’s like, how are we making anything better when we take the house? Maybe the house is a stabilizing force in the family? Maybe it’s grandma’s house and the kid’s 15 years old? Why would we take grandma’s house? Why would we take the family’s house based on not even a conviction but an accusation against a child who doesn’t even own the house? It’s way out of control.”

Paul’s express focus on civil asset forfeiture cases in this speech is interesting, given the fact that he’s also vehemently opposed to U.S. Attorney Loretta Lynch’s nomination to succeed Eric Holder as the next Attorney General of the United States on the grounds she is a leading advocate of using the practice. Lynch, who is black, is in open disagreement with even President Obama over the practice.

Paul then shifted his speech into another practice he finds to be an encroachment of a big and unruly federal government: mandatory minimum sentencing rules.

“What mandatory minimums do is say that if you committed an infraction, you have to serve a mandatory sentence of 15 years—sometimes life in prison,” Paul said.

Paul cited the case of Weldon Angelos, among others, to back up his case. Angelos was in 2004 sentenced to 55 years in federal prison for selling $350 worth of marijuana due to a bizarre set of circumstances, and he—like anyone else in federal prison—is ineligible for parole. The judge in the case, a George W. Bush appointee, asked Bush to commute the sentence, calling it “unjust, cruel, and irrational.”

“That’s outrageous, 55 years for selling $350 worth of marijuana,” Paul said. “You can kill somebody in Kentucky and be eligible for parole within 12 years. Something is wrong here.”

Generally speaking, Paul said, he thinks federal judges “should get more discretion.”

“Most of the judges, Republican and Democrat, are balking at this,” Paul said. “They’re saying give us discretion to listen to what the young person did, listen to the facts of it, listen to whether they’re remorseful, listen to whether or not they can work, listen to whether we can have another means other than incarceration.”

Paul made his argument in a socially conservative way to the Bowie State audience, arguing that it’s important for families to stick together and for kids to have a proper childhood and upbringing so that future generations can be more successful than prior generations. The current way things work in the criminal justice system–in some cases wrongfully, he argued–splits families apart.

“In 1980, there were 300,000 kids in America who didn’t have a father because their father was in prison,” Paul said. “There’s now 2 million kids in America who don’t have a father because their father is in prison. For those who think family structure is good, if we’re for families with a mother and father around, we need to be for fixing the criminal justice system.”

Paul then turned to his efforts to get nonviolent ex-convicts back to work in a way that they can be productive to society rather than simply drawing welfare checks because they have a criminal record that prevents them from getting hired.

“If we look at civil forfeiture, mandatory minimums, and then we look at other problems we have in our society, one of the problems we have is employment,” Paul said. “For us Republicans, we’re big on saying we don’t want people permanently on welfare—we want them to transition from welfare to a job. People look back at us and say well how am I supposed to get a job, I’m a convicted felon. I did my felony when I was 21, I’m 40 years old and still nobody will hire me. There has to be a way where we figure out how to get people back to work.”

The audience broke into applause again, before Paul told a story about the brother of a friend of his from Kentucky who has found it difficult moving forward with life after a nonviolent drug offense decades ago.

Thus, Paul said, he introduced the REDEEM Act with Sen. Cory Booker (D-NJ).

“What it does is it takes some of these minor felonies like drug possession and some drug sales, and says if you’ve been punished—you’re out of jail and you paid your debt to society—then there’s a certain time you should get rid of records,” Paul explained his and Booker’s legislation. “We’re not talking about violent crimes, we’re only talking about some nonviolent crimes. We should expunge your records so you can get back to work. The bill also, that I have with Cory Booker, it gets rid of solitary confinement for teenagers.”

Applause broke out again, before Paul shifted to another bill he’s leading called the RESET Bill that aims to reclassify some nonviolent infractions currently listed as felonies as misdemeanors.

“I also think that part of the problem with losing your ability to get employment, and losing your ability to vote is because we have a lot of things that are felonies that could be misdemeanors,” Paul said. “So I have what we call the RESET Bill and we take some felonies—mostly minor, all nonviolent, but mostly drug felonies—and we make them misdemeanors. We’re not saying it’s legal. We’re just saying it’ll be a misdemeanor. You will never lose your right to vote and you won’t lose forever your opportunity to work by having it permanently on your record. These are things that if we do we can radically transform our country.”

And Paul then shifted into his efforts to grant voting rights back to some nonviolent felons.

“The number one thing precluding people from voting is a felony conviction,” Paul said. “So I have a bill with Harry Reid that would restore federal voting rights if you’ve served your time for a nonviolent felony and you’re behaving yourself, you can get your voting rights back. I think it’s hard for people to feel like they’re part of the America that has life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness if they can’t vote. So we want people to be able to work, we want people to be able to vote.”

Paul then turned into laying out conservative economic and constitutional principles that he argues are necessary to protect not just the black community in the audience he was speaking to, but all Americans.

“How do we protect all of these things and how do we make it a better, more united America? I think we have to pay more attention to the Bill of Rights,” Paul said. “The Bill of Rights is there to protect all of us… It’s for the least popular among you. It’s for those who might have unorthodox ideas. It’s precisely for minorities. And you can be a minority because of the shade of your skin, or you can be a minority because of the shade of your ideology. You can be a minority because you’re African American or Hispanic, but you can also be a minority because you’re an evangelical Christian. There’s all kinds of instances where you can have minority opinions that need to be protected. The Bill of Rights should do this.”

While criticizing what’s called “indefinite detention”—which Paul describes as how the federal government can take an American citizen right now and send them “to Guantanamo Bay forever without a trial”—Paul questioned whether having such laws on the books could be dangerous.

“I had a debate on this with another senator on the floor and I said really, you can send an American citizen to Guantanamo Bay forever with no trial ever? And he said, yeah, if they’re dangerous. So it begs the question, doesn’t it, who gets to decide who’s dangerous and who isn’t?” Paul said, referencing a fight he had recently with Sen. John McCain (R-AZ) on the Senate floor.

“I don’t think this president is going to round up people of a race—and that’s what he said when he signed the legislation, he said ‘but I’m a good man and I will never do this,’” Paul added. “I’m not questioning whether the president is a good man. I’m questioning whether you want a law on the book that requires our leaders to be good people.”

Paul then brought up the Founding Fathers, citing James Madison’s writings about the then-young Republican and warnings he had for the future about the potential for the abuse of power.

“There have been times in our history when we have let down our guard. Madison wrote about this when Madison said that if government were comprised of angels, we wouldn’t need these laws,” Paul said. “We’d be fine. If government were comprised of angels, it wouldn’t matter if there was a potential for bias. Remember the times when you didn’t get due process. Remember the times in our country when there were groups like Japanese Americans in World War II who didn’t get due process and were incarcerated without trials. That’s why we have these rules. If it’s not this president, it’s the next president or the next president or the president thereafter.”

Paul also laid out how he believes the NSA spying program, where Americans’ cell phone records are being collected by the federal government on a massive scale, is something he thinks “goes against justice and the ideas of justice.”

“Every one of your phone records is being collected and stored. Every cell phone record probably in America. They won’t tell us, but in all likelihood the vast majority of phone records are being collected,” Paul said. “But if you look at the warrant, it doesn’t have your name on it. If you look at the Fourth Amendment, it says it’s supposed to have your name. It’s supposed to specify who you are, what you did, what they want to look at and then they go to a judge and they ask for probable cause. But you know what the warrant says that has all of your phone records? It says Verizon on it. I don’t know anybody named ‘Mr. Verizon.’ I don’t think you can write one single warrant and get the records of 20 million people, or 50 million people’s records. In fact, we fought the Revolution over this. In the Revolution, they called these things ‘writs of assistance.’ They were generalized warrants. That’s why we wrote the Fourth Amendment.”

Paul said that without these “Constitutional protections” in place, more and more minority groups—whether racial, ethnic, religious, or otherwise a minority—could be targeted wrongfully at some point in the future.

“Think about what happened in the 1960s. Think about how Martin Luther King’s phone was tapped,” Paul said. “Think about how hundreds of people involved in the Civil Rights Movement had their phones tapped. Think about how many people who protested against the war had their phones tapped. You have to have these protections not because there is one particularly bad person in government, but because there is the potential for bad people some day to take charge of government.”

Paul went on to note that his arguments for criminal justice reform are not along racial lines, but because of the fact that under the thumb of big government the black community across America has struggled economically for decades—and it’s conservative education and economic policies that are what’s needed to bring vibrancy back to the black community and inner cities.

“Criminal justice is not a black or white problem. It’s not a black or brown problem,” Paul said. “What it is is it’s a poverty problem. But the thing is we have to be careful to make sure that the Bill of Rights applies to every individual and if there’s one thing I want to get across to you is it’s we have to defend the Bill of Rights.”

With regard to education, Paul pushed for school choice and for education to be up to the parents—meaning no Common Core standards written by Washington bureaucrats from what Paul called the “educational establishment”—and argued that only when this happens will there be a chance for true equality in education.

“How do we equalize education? Education is the great equalizer,” Paul said. “We fought for Brown V. Board of Education in the ’50s and we got the schools together and we got integration, but there still is a lack of equality in the schools, there’s no other way to put it… A lot of the problem I think can only be fixed if we allow more innovation. That means less rules from Washington. Allow competition and allow people to choose which schools they go to in each of the cities. If there’s a better school in the suburbs, let people drive out to the suburbs if they want to go to that school. School choice will allow schools to be equal, but right now I think our concern is that the people making the decisions are the educational establishment and not the parents.”

Paul wrapped up his speech by discussing what he calls “economic freedom zones”—a stimulus package where instead of the government injecting taxpayer cash into an economically deprived area, the government cuts taxes and regulations dramatically so businesses can grow freely quickly—and how those would revive downtrodden inner cities like nearby Baltimore or Detroit.

“Finally, what we have to do is we have to figure out how to get economic equality,” Paul said. “I’m not talking about some sort of equality of outcome, I’m talking more about equality of opportunity. I think that we have to look at something new. We’ve tried passing money out—look at my state. Appalachia has gotten money for 60 years. We tax everybody in the country and then we send it to Appalachia. It’s still poor, Appalachia is still as poor as it ever was. We have pockets of poverty in Louisville that are just as poor as they ever were.

“The problem is if you give me the money and ask me to give it to somebody, people don’t know who to give it to. You give it to John Smith and say open a business and we don’t know if John Smith or Mary Smith is good at opening a business. The marketplace does though. Every day when you go out and you spend your money in a restaurant or a Wal-Mart or a Target or a K-Mart, you’re spending your money and you’re voting on which businesses will succeed. So I say if we want to stimulate Detroit—Detroit’s got 20 percent unemployment, thousands of acres of abandoned housing—so if we want to do something for Detroit, why don’t we dramatically cut the taxes for Detroit.”

The audience applauded loudly before Paul explained more about his idea.

“Jack Kemp was the first person to really talk about something like this, he called them enterprise zones,” Paul said. “I call them freedom zones. What we do is we take tax cuts to areas that have high unemployment, low growth and high poverty and then what we do is we dramatically cut the taxes—not a little bit, but almost completely wipe out federal taxes so they can have more money. So in Detroit it’d be a $1.3 billion tax cut. For Baltimore, it’d be a $900 million tax cut over 10 years.”

The audience erupted in applause again.

“Why does this work better than a government stimulus?” Paul said. “We tried a government stimulus—we did it four or five years ago—we gave a bunch of money, almost a trillion dollars, I think it was $800 billion we gave out. But we didn’t know who to give it to. So when we divided it up, it was about $400,000 per job. But if you give it back to the people who are already succeeding—look at Baltimore. Even though Baltimore has pockets of poverty, there are businesses there that are succeeding. We don’t give it to the brand new person who we won’t know whether they’ll be good at business, [instead] give it to the person who’s already in business and they’ll hire more people.”

Paul ended the address by laying out how he believes “the two Americas that Martin Luther King talked about can come back together” and that because of an “undercurrent of unease” in America due to big government, he thinks “it’s imperative that we do it.”

“I’ve been to Ferguson, I’ve been to Chicago and Detroit and other places with a great deal of poverty,” Paul said. “Some of this is government—government has done the wrong things sometimes, politicians. Police are just trying to do their jobs for the most part but the politicians have done a bad job of creating criminal justice and we need to try to fix that. We need to fix our educational system but we can’t just let the establishment say we’re not going to let it change—that’s what’s been going on for 30 years now and until we allow innovation we won’t get better. And finally we have to have the debate about who best spends money. Are the politicians smart enough to know how to spend it? Or should we send it back to Baltimore? Do we want to make Baltimore richer? Leave more money in Baltimore. Can we make Baltimore richer and have more jobs by not sending it to Washington in the first place?

“I’m a big believer in freedom, I’m a big believer in ingenuity, I’d say if we give more freedom back to the people, we’ll see success like we haven’t seen in a long time.”

The audience rose in applause yet again, giving him a standing ovation before he took questions via a moderator.

Watch Rand Paul’s full speech via C-SPAN.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.