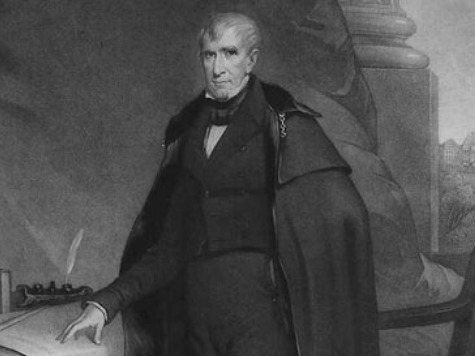

The New York Times recently reported on how modern epidemiology may be changing a nearly two-century-old diagnosis of the first president to die in office. Though most American’s could not pick the ninth president out of a lineup, William Henry Harrison’s dramatic election and untimely death are some of the most colorful events in American political history.

“Old Tippecanoe,” as Harrison was nicknamed for winning the Battle of Tippecanoe against legendary Indian chief Tecumseh, died just a month after being sworn in. According to his doctor, Thomas Miller, the official diagnosis was: “Pneumonia of the lower lobe of the right lung, complicated by congestion of the liver.”

The 1840 presidential election is legendary, even though the candidates are relatively obscure. It was the first truly “modern” election with two national parties, party platforms, get-out-the-vote campaign tactics, slogans, and rampant demagoguery.

Democrats had more than a decade of success under Presidents Andrew Jackson and Martin Van Buren. Van Buren, often called the “Little Magician” for his somewhat diminutive stature and reputation for his masterful–though opponents would say “underhanded”–politicking, had cruised to victory in the 1836 presidential election. However, a downturn in the economy led to a challenge from the newly-formed Whig Party. William Henry Harrison was chosen by the Whigs because he was a war hero and had a very short history of policy positions. Democrats were going to get a taste of their own medicine.

The Albany Evening Journal noted Harrison’s lack of policy credentials and mocked his supporters, coining the phrase, “Without a why or wherefore, we’ll go for Harrison therefore.”

The Whigs brought on Virginian John Tyler, who was closer to Democrats in policy but balanced the ticket, adding his name to the famous slogan, “Tippecanoe and Tyler too!”

One Democratic newspaper blasted Harrison, saying, “Give him a barrel of hard cider, and settle a pension of two thousand a year on him, and my word for it, he will sit the remainder of his days in his log cabin by the side of a ‘sea coal’ fire, and study moral philosophy.”

The Whigs turned this statement into a badge of honor, playing up Harrison’s “humble” origins, and ran him as the “log cabin and hard cider” candidate. This appeared as pure sophistry and demagoguery to Democrats, who noted that Harrison was not poor at all, but had been born into an aristocratic Virginia family–his father had signed the Declaration of Independence. He had since moved to the Ohio frontier, but lived in relative comfort.

An infuriated Democrat sneered:

We speak of the divorce of bank and state; the Whigs reply with a dissertation on the merits of hard cider. We defend the policy of the administration; the Whigs answer ‘log cabin.’ We urge the honesty, sagacity, statesmanship of Van Buren, and the unfitness of Harrison, the Whigs answer that Harrison is a poor man.

Events were held and the cider flowed, never had there been so much hoopla in a presidential election. This led to further howls of anger from Democrat opponents.

A Democrat paper wrote:

While we write, we are surrounded by log cabins on wheels, hard cider barrels, canoes, brigs, and every description of painted device, which, if a sober Turk were to drop among us would induce him to believe we were a community of lunatics or men run mad… We never before saw such an exhibition of humbug.

The down economy caused by the “Panic of 1837” and Whig flimflammery led to a victory for Harrison in one of the highest turnout elections in American history.

Harrison had often been criticized for being a geriatric during the campaign. He was 68 years old, which made him the oldest president elected at the time. In order to prove his vigor to Americans and his doubters wrong, Harrison gave the longest inaugural address in American history. The 8,445 word manifesto was delivered on a cold, rainy day in Washington D.C., and Harrison spoke without a hat, gloves, or warm clothing.

Two weeks later Harrison became gravely ill and he summoned his doctor. “The disease was not viewed as a case of pure pneumonia; but as this was the most palpable affection,” the doctor noted. “The term pneumonia afforded a succinct and intelligible answer to the innumerable questions as to the nature of the attack.”

Harrison complained of fatigue and anxiety, not lung issues, and the doctor was baffled. The New York Times noted that D.C. did not have a sewer system at that time and that this offers modern-day researchers some clues as to the true nature of his affliction. Sewage was dumped on public ground right next to the White House, adding to the unsanitary conditions to the fetid swamp that was the nation’s capitol.

The NYT wrote:

That field of human excrement would have been a breeding ground for two deadly bacteria, Salmonella typhi and S. paratyphi, the causes of typhoid and paratyphoid fever — also known as enteric fever, for their devastating effect on the gastrointestinal system.

Harrison had a history of dyspepsia and intestinal ailments, and the D.C. swamp undoubtedly made this worse. Most of the “treatments”–including opium and enemas–that Harrison’s doctor administered actually made the problem worse, and he developed the classic signs of entric fever and sepsis. Harrison expired on April 4, 1841, just 32 days into his presidency. That Harrison died because he was literally full of crap would have been no surprise to Van Buren and the bitter Democrats of that time.

The abysmal conditions of Washington D.C. and a history of health problems did Tippecanoe in, and he never put his stamp on the presidential office. New President John Tyler vetoed most of the Whig legislation that went through Congress and he was literally thrown out of the party while serving out his one term. The Whig Party died just over a decade later, another casualty of the DC swamp.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.