In the first installment of this trilogy, we explored how many big decisions in America are made as the result of institutional behavior, as opposed to any sort of ideology, left or right. That is, institutions have their own gravity, and their own momentum–and often there’s no stopping them.

And so, for example, Comcast’s acquisition of Time Warner Cable seems destined to happen. Sample headline in The Financial Times: “Comcast confident of TWC deal approval.” Speaking of Comcast executive vice president David Cohen, the FT noted:

Mr. Cohen is a major fundraiser for the Democratic Party, has held events for President Obama at his home and attended the recent White House state dinner for French President François Hollande.

In other words, when big institutions meet politics, the result is usually a victory for both. The institutions get the legal clearance that they want, and the politicians get the campaign contributions that they want–and the bureaucrats tidy everything up and declare it all to be legal. That’s the way things go these days; it’s a fusion of big business and big government.

Still, we might wonder where these acts, and their actors, came from. As we asked in the first installment, “Who is ‘They?'” Where, for example, did we get our current ideas about corporations and their corporate managers? And where did we get the professionalized and credentialized civil service that ratifies these corporate actions?

We can immediately observe that this corporatist rise is relatively recent. The first business school, for example, was founded in France in 1819; the first business school in the US, Wharton, was founded in 1881. Schools of public administration are yet more recent; the origins of Harvard’s Kennedy School reach back only to 1936.

One who described and analyzed this process, in real time, was the American writer James Burnham. More than seven decades ago, Burnham, then a leftist journalist, published The Managerial Revolution: What is Happening in the World. The work was the surprise best-seller of 1941, resonating with readers because it made a bold claim: the managers were taking over.

That is, managers, and not the communists, were winning–although there were communist managers. And not the fascists, either–although there were fascist managers. And not the capitalists, either–because the capitalists had ceded control of their assets to the managers.

Burnham’s sly genius was to sweep all managers–red, brown, and red-white-and blue–into the same category, without any regard to their espoused ideology. After all, Burnham declared, it was not ideological behavior that mattered, but rather, institutional behavior. First and foremost, managers were loyal to themselves, to each other, and to their organization. And that was their ideology, not some far-off notion of God, country, or the class struggle. The managers were a class, boasting a class consciousness, and they would do whatever was necessary to stay in power.

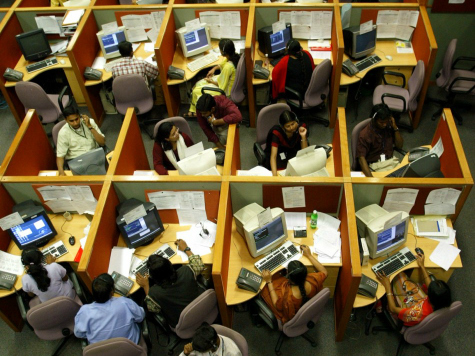

In Burnham’s telling, all across the planet–from Washington, DC, to London, to Berlin, to Moscow, to Tokyo–powerful men were sitting in their offices, hunching over reports and documents to read and sign, attending meetings and conferences, issuing orders that would move down through the hierarchy so that the lowliest functionary would know what to do.

Were these men–and they were almost all men–wearing uniforms, or were they wearing business suits? According to Burnham, it didn’t really matter. Were they on the left, the right, or in the middle? That didn’t really matter, either. What mattered was that they were managers, in charge of industries, armies, and societies.

As Burnham said of the managers, “What’s clear is that there is a universal class, with universal assumptions.” And so wherever they were, they behaved in pretty much the same way; all differences–theological, political, ideological –mattered less than their similarities. They were all “technocrats,” a word that came into existence only in 1919.

We might note, incidentally, that Burnham’s point was made earlier, in fictional form, by the haunted novelist Frank Kafka. In Kafka’s bleak vision, modern society had created forbidding castles of bureaucratic power, and the individual was powerless in the presence of such power.

Meanwhile, Burnham, writing from the perspective of 1941 as World War Two raged–even before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor – observed:

Today the managers are carrying on a similar triple battle… against the capitalists… against the masses… and against each other for first prizes in the new world.

And who would win this triple battle? Who would gain these planetary first prizes? Burnham was betting on the managers, and many important contemporaries agreed with his analysis. The great Christian writer C.S. Lewis, in the preface to The Screwtape Letters, published the following year, 1942, was moved to observe:

I live in the Managerial Age, in a world of “Admin.” The greatest evil is not now done in those sordid “dens of crime” that Dickens loved to paint. It is not done even in concentration camps and labour camps. In those we see its final result. But it is conceived and ordered (moved, seconded, carried, and minuted) in clean, carpeted, warmed and well-lighted offices, by quiet men with white collars and cut fingernails and smooth-shaven cheeks who do not need to raise their voices. Hence, naturally enough, my symbol for Hell is something like the bureaucracy of a police state or the office of a thoroughly nasty business concern.

In other words, Lewis accepted Burnham’s concept, even as he abhorred it.

Another who accepted Burnham was George Orwell. In 1946, Orwell wrote, “As an interpretation of what is happening, Burnham’s theory is extremely plausible.” Indeed, Orwell’s classic 1984, published three years later, owes a debt to Burnham, insofar as Orwell’s three mega-nation states were basically the same, even as they continuously warred against each other. As we have seen, Burnham had called it earlier in the decade. The managers would be fighting “against each other for first prizes in the new world.”

So where does Burnham stand now? What to make of The Managerial Revolution 73 years later? We might note that in his later years, Burnham became a conservative; he was a prominent part of William F. Buckley’s National Review.

Yet that 1941 work is his most famous, and it haunts us still. To be sure, he did not know about the full horrors of Hitlerism and Stalinism. So in that sense, Burnham was giving American managers a bad rap by lumping them together with the managers of death camps.

Nevertheless, in his argument that managers would displace fascists and communists, he was correct; today, there are no fascists and communists to speak of. Of course, as we survey the economic systems in, say, China and Russia, we see that something much less than free enterprise is dominant there. Indeed, the authoritarian systems of those countries–in which the capitalists can be rich only so long as they kick back some of their wealth to the managers–could be described as a kind of residual communism, fascism, or both.

In America today, what’s the situation? Do we have a free market, or is it a kind of crony capitalism? Do the people rule, or do the institutions rule? Are we in charge, or are “They” in charge? We all sense the answer to those questions.

Today, the course of our lives, whether we like it or not, is substantially defined by managers in the conflated public and private sectors–just as Burnham had foreseen, many years ago.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.