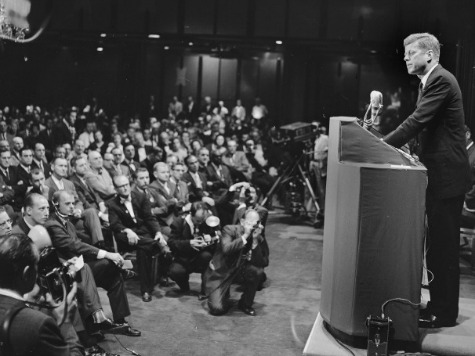

On September 12, 1960, John F. Kennedy delivered an historic speech to a group of Protestant clergy in Houston — the Greater Houston Ministerial Association — an address that continues, to this day, to be the subject of much discussion among Catholics.

The nagging questions are whether JFK’s speech was simply a rhetorical attempt to shake off the intense Protestant bias against him at the time, whether it served as a demonstration to Catholic politicians of how to leave your faith behind in public office while still calling yourself a “Catholic,” or whether he taught that there really is no difference between what is “right” to do as an American and what is “right” as a Catholic.

Though it is said that John F. Kennedy attended Mass even as he campaigned across the country, the nation’s first Catholic president kept outward signs of his faith to a minimum. Some say his privacy about his faith was a function of his own reserved style, while others believe JFK knew his Catholic faith would be a prominent subject of the political fight of his life.

In 2007, Nancy Gibbs wrote “The Catholic Conundrum” for Time, in which she advances the notion that JFK presented “the case study for candidates ever since who have faced some version of the Religion Test.” Current-day Catholic writers still consider whether the outcome of his “test” has set a positive example for Catholics in public life.

The “Catholic issue” would indeed be prominent, since by the time JFK was a presidential candidate in 1960, the Catholic population in the United States was about 42 million, more than double what it had been in 1928 when Catholic Al Smith ran for the presidency.

Gibbs wrote about Kennedy’s faith life:

Kennedy wore his faith lightly; he was “casual about religious rituals and observances,” his sister Eunice once said, and “a little less convinced about some things than the rest of us.” But as Thomas Maier recounts in The Kennedys: America’s Emerald Kings, his letters home during the war suggested he was a man on a spiritual journey, if a private one…his close adviser Ted Sorensen says in all their years together, they never discussed his personal views of man’s relation to his Creator.

However, Kennedy knew that with a run for Congress in 1946 in a heavily Catholic town like Boston, demonstrations of Catholic faith in public could be helpful. Boston’s Archbishop Richard Cushing invited JFK to recite the rosary with him on the radio, and a photo of Rose Kennedy and her son presenting a $600,000 donation to Cushing for a new Catholic hospital for children appeared in the Boston Pilot.

A presidential race was a completely different challenge, however. During his campaign against Republican Richard Nixon, Kennedy faced fear and bigotry, two strong enemies that he would ultimately conquer with a vigorous affirmation of a stiff boundary between church and state.

As George J. Marlin writes at The Catholic Thing, throughout much of the presidential campaign of 1960, “392 different anti-Catholic publications were distributed to voters, with an estimated circulation as high as 25 million.” The distributed pamphlets and brochures publicized that a Catholic’s first allegiance is to the pope; that a Catholic president will establish a Catholic state; and that a Catholic president will force his Church’s morality on the American people.

In his Houston address, Kennedy declared:

I believe in an America where the separation of church and state is absolute–where no Catholic prelate would tell the President (should he be Catholic) how to act, and no Protestant minister would tell his parishioners for whom to vote–where no church or church school is granted any public funds or political preference–and where no man is denied public office merely because his religion differs from the President who might appoint him or the people who might elect him.

I believe in an America that is officially neither Catholic, Protestant nor Jewish…and where religious liberty is so indivisible that an act against one church is treated as an act against all.

Finally, I believe in an America where religious intolerance will someday end–where all men and all churches are treated as equal–where every man has the same right to attend or not attend the church of his choice–where there is no Catholic vote, no anti-Catholic vote, no bloc voting of any kind–and where Catholics, Protestants and Jews, at both the lay and pastoral level, will refrain from those attitudes of disdain and division which have so often marred their works in the past, and promote instead the American ideal of brotherhood.

That is the kind of America in which I believe. And it represents the kind of Presidency in which I believe–a great office that must neither be humbled by making it the instrument of any one religious group nor tarnished by arbitrarily withholding its occupancy from the members of any one religious group. I believe in a President whose religious views are his own private affair, neither imposed by him upon the nation or imposed by the nation upon him as a condition to holding that office…

But let me stress again that these are my views–for contrary to common newspaper usage, I am not the Catholic candidate for President. I am the Democratic Party’s candidate for President who happens also to be a Catholic. I do not speak for my church on public matters–and the church does not speak for me.

Whatever issue may come before me as President–on birth control, divorce, censorship, gambling or any other subject–I will make my decision in accordance with these views, in accordance with what my conscience tells me to be the national interest, and without regard to outside religious pressures or dictates. And no power or threat of punishment could cause me to decide otherwise.

Kennedy’s words might easily be described as inspirational, and they served, perhaps, to humble Protestant ministers who feared the Pope could become the next President of the United States. However, as conservative Catholic writer George Weigel writes in National Catholic Register this week:

No one should doubt that hoary Protestant bigotry was an obstacle the Kennedy campaign had to overcome in 1960. Still, a close reading of the Houston speech suggests that Kennedy neutralized that bigotry, not only by deft rhetorical moves that put bigots on the defensive, but by dramatically privatizing religious conviction and marginalizing its role in orienting a public official’s moral compass.

Kennedy, Weigel writes, essentially signaled the start of “an American public space in which not merely clerical authoritarianism, but religiously-informed moral conviction, is deemed out-of-bounds.”

The secular media, as Marlin writes, declared JFK’s Houston speech a triumph, while prominent Catholics were vexed by his attempt to sever any connection whatsoever between a public official’s religious creed and his public life.

Marlin quotes Jesuit Catholic political thinker at the time, John Courtney Murray as objecting, “To make religion merely a private matter was idiocy.”

Murray had advised Kennedy to emphasize in his address that “while Church hierarchy should never coerce a public official, they should always be free to instruct Catholics from the pulpit as to the Church’s teachings on moral issues debated in the public square.”

In retrospect, Marlin sees JFK’s comments about religion being “private” as opening a “can of worms that haunts American Catholics to this day. That’s because many Catholic pols argue that one’s religious views should not have any role in the public square, because faith is nothing more than a personal thing.”

Fifty years later, American Catholics are hardly dealing with public officials who would want the United States to become a “Catholic state.” Nancy Pelosi, Joe Biden, Mario Cuomo, John Kerry, and other self-proclaimed “Catholics” seem to have found the ultimate degree of separation between the tenets of their Catholic faith and their public service.

Marlin concludes that, while the election of John F. Kennedy removed a barrier in politics for American Catholics, it also came at a great price.

“By ceding ground to secularists in his Houston speech,” he writes, “JFK marginalized those Catholics in the public square who are actually guided by Church teachings, and they have been branded public villains ever since.”

John B. Kienker, managing editor of the Claremont Review of Books, however, has a different view of Kennedy’s Houston speech.

Kienker contrasts JFK’s address with that of Mario Cuomo at the University of Notre Dame in 1984, in which the governor of New York stated that although he opposed abortion personally he would continue to support it publicly.

“Delivering his address… Cuomo certainly wanted it to appear as if he were building on the foundation laid by John Kennedy in Houston…” Kienker writes. “But unlike Cuomo, Kennedy did not call for religious indifferentism or moral relativism. His support for an ‘absolute’ separation of church… was… a firm rejection of theocracy, which too many Americans still suspected the Catholic faith required.”

“The crucial difference between Kennedy’s and Cuomo’s speeches is that Kennedy denied, as he put it, ‘any conflict to be even remotely possible when my office would require me to either violate my conscience or violate the national interest,'” Kienker writes. “What is right to do as an American doesn’t conflict with what is right to do as a Catholic because the laws of nature and of nature’s God cannot conflict.”

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.