President Obama and Congress continue to wrestle with competing ideas to fix America’s housing crisis, ranging from abolishing Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to introducing new regulations for repairing the rickety mortgage-financing system years after it crashed. To understand the enduring nature of today’s housing-system mess, it is not really necessary to do much more than to look backward. To look, that is, at the careers of two former prominent politicians, each of whom has played an integral role in American finance in recent decades.

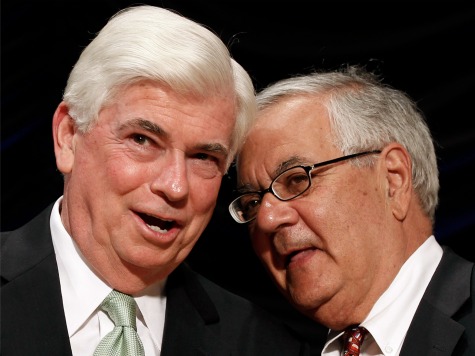

The first is former Connecticut senator Chris Dodd; the other is former Massachusetts representative Barney Frank. Both men have a lot in common. Both are Democrats. Both were influential members of their chambers’ banking and financial-services panels (they chaired their respective committees when Congress passed the Dodd-Frank financial-reform law in July 2010). Both personified the cozy tripartite relationship involving big banks, big housing and big government. And both pooh-poohed the skeptics and stoutly defended Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac–long after many experts were warning that those huge government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) had overextended themselves in the frothy U.S. housing market before the crash.

When it came to listening to dissenting voices, Frank was a bully and proud of it. During one subcommittee hearing, when Congressional Budget Office director Robert Reischauer expressed concerns about taxpayer liabilities if Fannie and Freddie encountered financial difficulty, Frank responded so vehemently that the subcommittee chairman, the gentlemanly Texan Henry B. Gonzalez, admonished him to stop badgering the witness. His propinquity to Fannie Mae was manifest when the company hired his domestic partner upon his graduation from business school at Dartmouth and in the $75,000 that Fannie donated to a Boston nonprofit group cofounded by Frank’s mother. As Gretchen Morgenson and Joshua Rosner observe in their 2011 book, Reckless Endangerment, “Frank was a perpetual protector of Fannie, and those in his orbit were rewarded by the company.”

And what about Dodd? He, too, defended Fannie and Freddie, denying that they were in serious financial straits even after Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson sought to augment capital and regulatory requirements for the GSEs as part of a bailout package. Dodd promoted legislation to assist troubled subprime-mortgage lenders such as California-based Countrywide Financial when they faced collapse after the housing bubble burst. It later turned out that he had accepted below-market mortgage rates from Countrywide for refinancing his Washington and Connecticut homes. The Senate Ethics Committee concluded that, while Dodd had not knowingly pursued special treatment, he should have investigated the matter when he discovered that Countrywide had placed him in a special category of customers.

Mark Calabria, director of financial-regulation studies at the Cato Institute, wrote in 2010 that nothing in the Dodd-Frank legislation ended the huge intervention by the U.S. government in the mortgage market. Nor would it help avoid the next crisis.

Read the rest of the story at The National Interest.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.