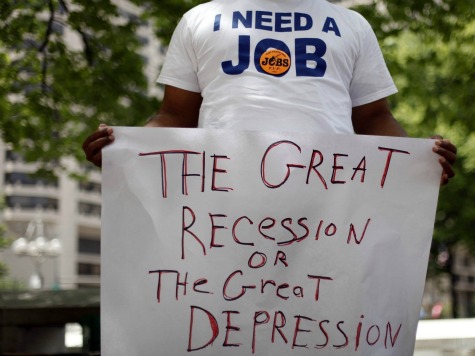

The Labor Department announced the economy added 175,000 jobs in May, but that is hardly the 360,000 thousand jobs needed each month to bring unemployment down to 6 percent over the next three years.

The jobless rate rose to 7.6 percent.

Adding in discouraged adults and part-timers who want full-time jobs, the unemployment rate becomes 13.8 percent. And, for many years, inflation-adjusted wages have been falling and income inequality rising–this remains a buyer’s market.

Sluggish growth is one culprit–the Bush expansion delivered only 2.1 percent annual GDP growth–that’s about the same as the Obama recovery after 45 months.

Now, defense cutbacks negotiated with Congress during President Obama’s first term have subtracted some $62 billion from federal spending since last fall, and an additional $200 billion in higher taxes and sequestration spending cuts are further reducing consumer outlays and government spending in the second and third quarters of this year.

With all this fiscal drag, economists expect growth to slow to less than 2 percent in the second quarter, and jobs creation is likely to slow through the spring and summer. With southern Europe’s depression dampening continental demand for goods made in Germany and other northern states, the prospects for U.S. exports and cut-priced competition from Europe in U.S. markets is heating up–growth and jobs creation could stay depressed for a long time.

Similarly, the Japanese Prime Minister’s much heralded stimulus and reforms appears to come down to debasing its currency to jack up exports to North America, and very little else–labor market reforms have been shelved, and no sign of easing immigration policy or new incentives for family formation to counter its declining population–that spells yet more cut-rate competition for U.S. manufacturers.

It is hard to imagine the Federal Reserve could do more to support growth. Already, it is buying virtually all the new mortgage backed securities and 70 percent of the new federal debt issued each month.

This is keeping interest rates low and boosting new home construction, but new home construction is less than 3 percent of the economy and cannot carry the recovery. Low rates also penalize the elderly who rely on CDs and fixed-income investments, reducing their spending on goods and services. Many cash-strapped elderly have returned to work, often taking jobs from younger workers.

Stronger growth would help and is possible. Forty-five months into the Reagan recovery, GDP was advancing at a 5 percent annual pace–nowadays, that pace would bring unemployment down to 5 percent pretty quickly.

More rapid growth requires importing less and exporting more–dealing with the $450 billion trade deficit on oil by drilling more offshore and in Alaska, and with China, by addressing its undervalued currency and protectionism.

Faster growth also requires rightsizing business regulations to make investing in new jobs less expensive and time consuming. Regulatory enforcement is needed to protect the environment, consumers, and financial stability but must be delivered cost effectively and quickly to add genuine value.

Overall, more jobs require trimming back on tax increases and spending cuts, while enacting more pro-growth trade, energy, and regulatory policies.

Peter Morici is an economist and professor at the Smith School of Business, University of Maryland, and widely published columnist. Follow him on Twitter.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.