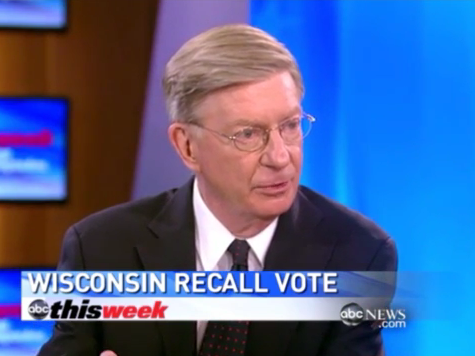

Dr. George Will is a respected social scientist and acclaimed writer, but he’s not a lawyer. And he shows it by suggesting the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) is unconstitutional as the Supreme Court prepares to hear a challenge to that federal statute this week in U.S. v. Windsor.

DOMA prevents the federal government from giving federal marital benefits to gay marriages or polygamous marriages, and the Constitution allows Congress to make that judgment.

Will has made valuable contributions to the issue of gay marriage. And on a personal note, I’m grateful for Will’s very positive Washington Post column last week on the Supreme Court legal brief that Prof. Nelson Lund and I authored on behalf of nationally-renowned social scientists and filed in the marriage litigation.

Our brief explains how there is currently no social science supporting the conclusions of liberal interest groups like the American Psychiatric Association when they support gay marriage. “Back off, man, I’m a scientist,” might have been a great line for Bill Murray in Ghostbusters, but it’s a lousy way to interpret the Constitution and make federal laws.

In our constitutional system, states define marriage. But that means states determine issues such as how old you must be to get married if you are not yet an adult, or which relatives (e.g., brothers and sisters, first cousins, second cousins) are considered too close to be married without committing incest. Until recently, all those laws required two persons, one man and one woman.

Will mistakenly says that before 1996 federal law accepted whatever each state’s definition was about marriage. That’s false, as Paul Clement–the lawyer defending DOMA at the Supreme Court and probably the greatest Supreme Court lawyer alive today–explains in detail in his brief submitted to the Court.

There are over 1,000 provisions of federal law that involve marriage, and while most do not define marriage (and therefore rely upon DOMA), others separately define marriage and ignore any contrary definition from states. For example, if you are married but separated from your spouse and living separately, federal law does not permit you to file a married joint tax return; you must file as an unmarried person. Or if you are married to a foreigner and that person is not currently in this country, you must file an unmarried person tax return. Or if you want to claim social security survivorship benefits, the Social Security Act defines marriage as one man and one woman.

DOMA simply clarifies that this definition applies to every provision of federal law. Section 3 of DOMA, which the Court is considering this week, defines marriage as “a legal union between one man and one woman as husband and wife.”

Will is also evidently confused, saying that DOMA is unconstitutional because it’s not authorized by the Necessary and Proper Clause. He says the question becomes, “Does the federal government have the power . . . to define and protect the institution of marriage?” No, that’s not the question at issue, because defining a term is not any exertion of federal power.

The Necessary and Proper Clause is actually completely irrelevant to DOMA. If the law using “married” is a tax law, then that whole law is authorized by the Taxing Clause. If it’s Social Security benefits, then it’s the Spending Clause. If it’s military benefits, then it’s the Army Clause. If it’s determining who can immigrate with their spouse into this country, it’s the Naturalization Clause. And so on. All DOMA does is create a federal definition; it’s not an exertion of any congressional power and does not require some separate “necessary and proper” analysis.

One point not discussed by Will–but critically important–is the issue of polygamy. Over 50 nations on earth currently have legal polygamy, and many millions of people are in polygamous marriages. Studies even show that in this country there are currently 600,000 people in polygamous marriages. Yet the federal government does not recognize those marriages, regarding the man as only married to one woman in the marriage, and leaving the others will no recognition or benefits.

Imagine what a person’s tax return would look like if a man had four wives. You get to claim five personal exemptions, and everyone can cross-claim all child tax credits for all children born to all four women. The IRS would have to completely redesign Form 1040, and the resulting returns would have a significant fiscal impact on the nation.

And if you are, for example, a Muslim man immigrating from Saudi Arabia who was legally married to four women in that country–as is allowed in Islam–the federal government does not allow you to bring in your wives as “spouses.” As a family you are denied immigration. So federal law actively discriminates against law-abiding polygamists trying to enter into this country.

DOMA authorizes this, defining marriage as one man and one woman. If Will’s argument were correct, them the federal government would now have to recognize polygamy if any state in the country chose to do so.

For that matter, Windsor is a case about two lesbians who got married in Canada in 2007, long before their home state of New York created gay marriage in 2011. If the justices agree that the federal government must recognize their marriage and strike down DOMA Section 3, then they probably must recognize all foreign marriages, including all foreign polygamous marriages.

Under longstanding Supreme Court precedent, DOMA is constitutional because it is rationally related to advancing legitimate public interests. It involves conferring federal payments and other legal benefits, not determining who can and cannot get married. The Supreme Court has clearly held since Helvering v. Davis in 1937 that being a steward of taxpayer money gives Congress a legitimate interest in determining who can receive federal benefits. The only question was whether Congress was literally irrational in thinking that marital benefits should go to unions consisting of one man and one woman.

It’s also longstanding precedent, reaffirmed in U.S. v. Turley in 1957, that Congress defines almost all terms in federal law. Borrowing definitions from state law is a rare exception, not the rule.

George Will is a very thoughtful man. But he’s no more qualified to conduct a legal analysis than I would be to walk into the hospital room of one of my wife’s patients and attempt to diagnose and treat her patient. The fact that I’m married to a doctor and talk with her every day will never qualify me to practice medicine. And being an Ivy League-educated social scientist talking every day to lawyers will never qualify him to practice law.

In a National Review column by Ed Whelan (a brilliant constitutional lawyer who once clerked for the Supreme Court), Will was “snookered” by the false arguments offered by liberal law professors on this issue. But you don’t have to be a lawyer; anyone who reads Clement’s excellent brief can learn what the Constitution and the law says on this controversy.

Federalism means that the states are sovereign in their domain, and the federal government is sovereign in its domain. The feds can’t tell the states who can be married, and the states can’t tell the feds who must receive federal marriage benefits. The liberals’ argument here rejects the second part of that equation, and must be rejected by everyone who claims to adhere to the text and structure of the Constitution.

If the Supreme Court decides U.S. v. Windsor on the basis of the law, then it will uphold DOMA.

Breitbart News legal columnist Ken Klukowski is on faculty at Liberty University School of Law, and filed a brief for social scientists on the issue of marriage.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.