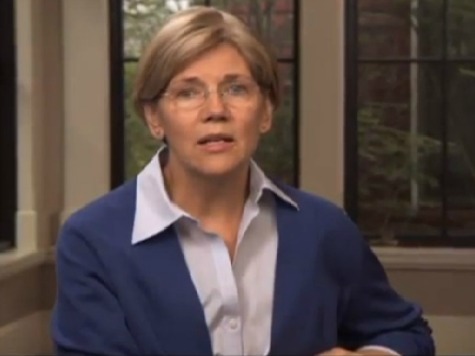

In her new “Family” television ad, Elizabeth Warren directly responds to the controversy surrounding her claims to Native American heritage.

Here are the three central claims Ms. Warren makes using the same phrasing she’s tested out with crowds over the past several months:

1. That she has Native American heritage.

2. That her parents were forced to elope because her father’s parents objected to their marriage due to her mother’s heritage.

3. That she did not benefit from “checking the box” as a Native American in a law school professor directory several times during the 1980s and 1990s.

Let’s analyze these three claims, one by one:

Claim #1: “[My mother] was part Cherokee and part Delaware.”

As Breitbart News and many other sources have documented in excruciating detail, there is zero credible evidence to support the claim that Elizabeth Warren’s mother had any Native American heritage, either Cherokee or Delaware. The only “evidence” Ms. Warren has ever presented to support those claims are her recollections and the recollections of her brothers that her mother and grandmother made such claims while they were children.

Claim #2: “[M]y parents had to elope.“

Ms. Warren repeated this claim that Breitbart News debunked in June at the debate with Scott Brown last Thursday.

Her parents were married in a religious ceremony in Holdenville, Oklahoma on January 4, 1932, twenty miles from their hometown of Wetumka, Oklahoma. The marriage was announced days later in their local Wetumka, Oklahoma weekly newspaper.

As Cherokee genealogist Twila Barnes notes, what Warren’s mother told her about the wedding, as described in this Boston Globe article, is simply not true. According to the Globe:

One day Warren, then about 7, asked her mother about her own wedding dress, and her mother said she had not had one. When Warren pressed for details, “she said no one came to her wedding at all.”

Alyne Geren, a friend of Pauline’s from school, possibly her best friend, attended the wedding. We know because she was a witness to the marriage.

Claim #3: “I never asked for, never got any benefit because of my [false] heritage [claims].”

When Ms. Warren decided to actively “check the box” and make the false claim that she had Native American heritage, she was, in fact, asking for the benefit of preferential treatment in future law school hiring.

In 1986, Elizabeth Warren “checked the box” and began listing herself as a “Minority Law Teacher” in the American Association of Law Schools directory. She continued checking the box until 1997, when she suddenly stopped the practice.

As I wrote in May here at Breitbart News, Warren also told faculty and students at Harvard Law School that she was a “woman of color” back in 1993. Harvard Women’s Law Journal published an article that spring which listed Ms. Warren as one of 250 “women of color” in legal academia:

The methodology the editors used in preparing the article for final publication indicates that it is likely that Warren provided the information which identified her as a “woman of color,” and that she actively consented to her listing as a “woman of color.”

While Ms. Warren did not benefit from these claims when she was hired at Penn in 1987, it was a different story at Harvard in 1993:

There is no evidence to suggest Warren’s newly-made claims of Native American ancestry… played a role in her hiring by the University of Pennsylvania.

There is, however, evidence to support the notion that she fostered a “Native American persona” which she later used to secure employment at Harvard Law School–the most prestigious law school in the country.

Five and a half years after being hired as the “trailing spouse” at the University of Pennsylvania, she was offered a tenured position during the spring semester of her professorship at Harvard on February 5, 1993, where students and members of the faculty and administration were well aware that she called herself a “woman of color.” Family circumstances prohibited her from accepting Harvard’s standing offer until the fall of 1995. Then, two years later, having used her undocumented claims of Native American ancestry to secure the golden ring at Harvard, she quietly stopped listing herself as a minority after the 1997 AALS directory.

Though the members of the Appointments Committee that recommended her hiring at Harvard may not have been familiar with this article and Ms. Warren’s self-identification as a woman of color, other members of the faculty who voted on the decision to offer her full-time employment likely were. When she was offered the job at Harvard in 1993 and accepted it in 1995, Ms. Warren benefited from this:

Five years of aggressive self-promotion as a woman of Native American ancestry at Penn from 1987 to 1992 laid the groundwork for her ultimate affirmative action coup–the standing offer of a tenured position made to her by Harvard in February 1993.

Todd Zywicki, George Mason University Foundation Professor of Law, who has been a vocal critic in the past of what he calls Warren’s academic fraud, elaborated on this pattern of behavior when he wrote recently at the Volokh Conspiracy, a well-known legal blog:

I have known from highly-credible sources for a decade that in the past Warren identified herself as a Native American in order to put herself in a position to benefit from hiring preferences…She was quite outspoken about it at times in the past and, as her current defenses have suggested, she believed that she was entitled to claim it.

Warren’s former colleague at the University of Pennsylvania Law School, Professor Charles Mooney, had an office across the hall from her during her entire time there. As he recalls, “She mentioned that she had Native American heritage. She didn’t keep that a secret, but I don’t remember any particular context where she raised it.” Other Penn faculty members agree. Her frequent claims of Native American heritage were well known and common knowledge.

Despite recent denials by members of the 1993 Harvard Law Schools Appointment Committee that hired Warren, an odd convergence of unusual circumstances suggests quite a different story: that Warren was likely offered tenure because the Harvard Law School administration was under significant political pressure from faculty members and an angry student body to check off the “woman of color” box.

Additional Factual Problems: Ms. Warren’s commercial has other problems. She makes this assertion about things her mother told her as a child:

As a kid, I never asked my mom for documentation when she talked about her Native American heritage. What kid would?

The question is designed to inoculate Ms. Warren from her obligation as an adult to seek the truth about her own heritage.

It turns out, a lot of kids interested in seeking the truth would. For instance, as a kid, my grandfather told me that the Leahy family moved to Quebec in the 1720s. I investigated the historical documents — as a kid — and discovered that it wasn’t true. The Leahy family didn’t move to Quebec until the early 1840s.

Consequently, I’ve never claimed that the Leahy family moved to Quebec in the 1720s, because I’ve determined based on evidence that it’s not true. My grandfather told me it was so, and while he may have believed it, it has been factually unsound.

In 1967 when I was twelve, my grandfather told me that a “Fenian Army” had camped on our family farm in Hemmingford, Quebec in 1867 for an evening on their way to a battle elsewhere in Quebec. “Fenians” were Irish-Americans who wanted to stir up a war between the United States and Britain to promote the cause of Irish liberty.

While, unlike Ms. Warren, I never became a state high school debate champion, I did have a curious mind and a desire to seek the truth. So I wrote to a Professor of History at the University of Toronto to verify my grandfather’s claim about that purported Fenian Army encampment. Much to my disappointment, the professor confirmed what I suspected; my grandfather had told me another tall tale. A ragtag group of several hundred Fenians had attempted an invasion of Canada in the late 1860s, but the battle they fought and lost took place some distance from our family farm, and their path of attack and retreat never came close to our land.

Millions of other Americans have been told stories about their heritage by their parents or grandparents that turn out not to be true. After learning that a family story is not true, anyone — adult or child — who repeats the false story is a liar.

But more importantly, Ms. Warren was a 34-year-old adult in 1984 when she first publicly claimed she had “Native American” heritage. That claim was made when she attached “Cherokee” to her name at the end of the plagiarized recipes she submitted as part of the Pow Wow Chow cookbook.

By this time, Ms. Warren had not only won the Oklahoma high school debate championship; she had graduated from high school, college, and law school, passed the bar in New Jersey, married, given birth to two children, divorced, remarried, and secured a tenured position as a Professor of Law at the University of Texas.

She first “checked the box” in the 1986 AALS directory as a Native American when she was 36 years old. At this age, she had an obligation to apply standards of evidence to her heritage claims appropriate for a professional academic adult. Yet, she did not, and still justifies “checking the box” of the AALS directories from 1986 to 1997 based upon the childish standard that “my mother told me, so it must be true.”

In the fifth and final sentence of her ad, Ms. Warren makes a statement that we will generously call a “bonus misstatement.”

Bonus Misstatement: “Scott Brown can continue attacking my family, but I’m going to keep fighting for yours.”

In Ms. Warren’s world, Scott Brown is “attacking [her] family” because he points out that her adult reliance on false statements made to her by her mother when she was a child were not sufficient evidence to justify her claim that she has Native American heritage.

Scott Brown is not attacking Ms. Warren’s family. He’s attacking her character, and the charges are sticking.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.