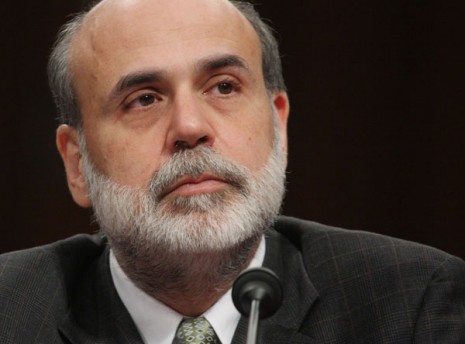

The G20, comprised of the leaders of the twenty most powerful economies in the world, met in Los Cabos, Mexico last week for a scheduled meeting to discuss global financial issues. This meeting was particularly important due to the debt crisis that is spreading across Europe, specifically the troubles in Greece, Spain and Italy that are challenging the survival of the Euro (the common currency of the seventeen-member European Union). With essentially all of the world’s wealth and military power represented at the G20, with one-on-one meetings between many of the heads-of-state of these nations, with all this power in one place – surely the global financial markets were focused on the intellectual decisions and carefully worded statements that would result from this assembly of leadership? Well, maybe not! The global financial markets were focused on one mild, bearded, former academic who was holding court in Washington, D.C. Yes, the world was waiting for words from the true power, the U.S. Federal Reserve Chairman, Ben Bernanke.

While world leaders in Los Cabos made sure that news cameras captured their serious facial demeanors and that all waiting microphones were served deep philosophical wisdom, it was Chairman Bernanke’s news conference last Wednesday that was the highly anticipated main event. His appearance before the media followed the conclusion of the most recent meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) of the Federal Reserve. The FOMC meets on a regularly scheduled basis to determine monetary policy and interest rate targets (the primary tool used by the Federal Reserve to stabilize the economy). The committee decided to leave interest rate targets unchanged. Short-term rates (those that are truly under the influence of the Federal Reserve) are currently between zero and one quarter of one percent, so lowering these rates was not an option. The FOMC decided, instead, to extend to the end of 2012 the Federal Reserve’s current program of maturity swapping. This action, referred to as “operation twist,” is a process of selling treasury bonds with maturities of less than three years that the Fed holds on its balance sheet, and using the proceeds to buy treasury bonds with maturities of between six and thirty years.

The current decision would convert approximately $267 billion of short maturities to longer maturities. The objective is to drive long-term rates lower by increasing the price of those longer maturities through increased demand. The theory is that lowering longer term rates would encourage more lending and therefore result in more cash flowing into the economy and stimulating growth. Operation twist started last year, and the Fed has already sold $400 billion of shorter maturities and purchased an equal amount of longer maturities. This action did help to drop the rate on the ten-year Treasury bond to historic lows but did little to stimulate lending. The hypothesis that another $267 billion of maturity swaps will make a difference was rejected by global markets last Thursday, as the heart was ripped out of commodities and equities. The Dow Jones Industrial Average suffered its third worse day of the year, dropping 250 points. Oil, gold and most other commodities crashed as well. The global consensus was that the world economy has stalled, is weakening, and there is little that even the all-powerful Fed could do about it.

Why twist? This is an important question and addresses the significance of where current economic and political ideology is today. The Federal Reserve has really only one means of impacting the economy, and that is control over interest rates. When the economy is in a more historically stable period of real growth, short-term rates tend to be around 2% to 3%. At the first sign of an economic slowdown, the Fed could begin a series of interest rate cuts. It does this by lowering the Federal Funds Rate (the rate that banks charge each other for overnight deposits) and by lowering the Discount Rate (the rate that the Fed charges banks for overnight borrowing from the Fed itself). This action sets a new benchmark for short-term rates. Treasury bonds, corporate borrowing and individual borrowing rates fall in unison with the new benchmark. Lower rates tend to stimulate borrowing, putting more cash to work in the economy and stimulating growth.

As the financial crisis of 2008 developed, the Fed quickly cut short-term interest rates to practically zero. To influence economic stimulus further, the Fed introduced a program of quantitative easing that became known as “QE.” The first iteration, QE1, was done in the fall of 2008 and targeted mortgage-backed securities held by banks. Simply put, the banks were holding large amounts of bonds that were collateralized by residential mortgages that were in risk of default due to the bursting of the real estate bubble at that time. The theory of QE1 was to have the Fed buy these bonds from the banks in exchange for deposits at the Fed. These deposits are accounted for as reserves at the banks. Banks can only lend money that is in excess of a level of required reserves that the banks must hold relative to their asset size. Hence, by selling their troubled mortgage-backed bonds to the Fed in exchange for Fed deposits – the banks converted risk assets into reserve liabilities and significantly increased their excess reserves. The Fed’s hypothesis was that the banks would then use these excess reserves to increase lending and therefore put more money to work in the economy and stimulate growth. Nice theory, but the reality did not play along.

QE1 resulted in the Fed adding $1.4 trillion to the banking system in the form of “electronic money” classified as Fed deposits. The banks did not increase lending for fear of risk and due to lack of demand by businesses and consumers. The Fed responded with QE2 after the midterm elections in November of 2010. This time the target was Treasury securities, and again those purchases from the banks were in exchange for Fed deposits. QE2 added another $600 billion in excess reserves at the banks.

Making matters worse, the Fed decided to encourage banks to raise capital, and further increase their excess reserves, by paying interest of Fed deposits. While the Fed is only paying one quarter on one percent or twenty-five basis points (0.25%), it is still risk free income for the banks and therefore discourages lending.

After $2 trillion of quantitative easing and no significant new borrowing by businesses and consumers who had become obsessed with reducing their debt, the Fed decided to go try another way to influence interest rates and encourage increased lending. Along came operation twist, which was first employed by the Fed was in 1960. Yes, it was named after the dance craze at the time – the “Twist!” While the dancing was fun, operation twist in 1960 only reduced long-term interest rates by fifteen basis points or 0.15%. Lending did not increase at that time and it is not increasing today.

So where are we? Interest rates are effectively at zero; bank reserves increased by $2 trillion due to quantitative easing; $400 billion of operation twist has already been accomplished; and now another $267 billion of “twisting” is in progress and with little to no increase in lending and therefore no impact on economic growth. The Fed used the tools it has and came up empty. Why? The problem is that while the Fed can have impact under certain conditions, it cannot move a giant economy that is being held back by ideological dogma. The Federal government under the current administration has taken the Keynesian view that the only way to move an economy is to borrow and spend large amounts of money. History has proven that this does not work.

In February of 2009, $780 billion of “stimulus” was put into economy and the economy continued to weaken. Four consecutive years of trillion dollar deficits to fund well intentioned income protection programs of food stamps and extended unemployment benefits as well as continued expansion of the Federal government, resulted in a 60% increase in the national debt from $10 trillion (when George W. Bush left office) to $16 trillion today. All of this debt and spending did nothing to stimulate long-term sustainable economic growth. Even John Maynard Keynes would be crying “uncle” by now!

The debt crisis in Europe emphasizes the failure of the Keynesian theory. Even the best socialists in Europe are beginning to understand that when there is no money left – there is no money left! The global markets want measures that will result in lasting growth and not short-term political posturing. The markets underscored this sentiment with a strong message last Thursday that they fear further global economic contraction that even the most powerful figure in the world, the Federal Reserve Chairman, cannot stop.

What now? The answer is again available to us from history. John Kennedy did it; Ronald Reagan did it; and George W. Bush did it – they all worked with Congress to lower tax rates and to lessen government’s grip on the private sector. The result was economic certainty and a clear path for the private sector to take risk. In all three instances, tax revenue increased from strong and sustainable economic growth. This time the necessity for certainty and less government is critical. Federalism has its benefits relative to national defense; interstate commerce; civil liberties; and similar matters. However, when it comes to the most impressive economic engine in history the American economy – the best role that government could play is to step aside and allow the people to innovate and create wealth.

Various studies over the past two years estimate that private and public corporations are holding more than $2 trillion in cash on their balance sheets; with an additional $1 trillion in overseas profits (after paying taxes to the countries where those profits were made); another estimated $3 trillion in private equity capital; and more than $2 trillion in excess reserve lending power in our banking system. Hence, if these studies are accurate, there is over an estimated $8 trillion of capital waiting to fund superior economic growth in our nation. Even if the actual available capital is half that estimate or $4 trillion, that is still powerful and debt free economic stimulus waiting on the sidelines. The only thing holding the private sector back is a failed ideology that government can control the private economy and that an extra-constitutional institution, the Federal Reserve (which was created by an act of Congress in 1913) could help the government in this miss-guided mission. Now that is twisted!

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.