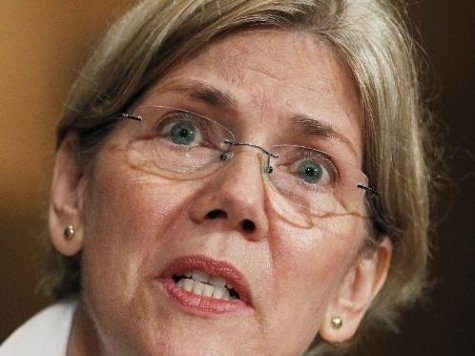

While Elizabeth Warren exploited Cherokee for special consideration at Harvard, real indigenous students suffered. At no time, evidently, did this “first woman of color at Harvard” do anything to help the appalling academic disparity between indigenous American students and those of other ethnicities.

For years the published test scores of indigenous students have shown a great need for educational improvement:

The Stanford 9 Achievement Test scores for Arizona schools reported this year by the Arizona Department of Education are about average for the nation. However, the scores for schools on the Navajo and Hopi Reservations, which were printed in last week’s Observer, are well below average and include some of the lowest scores in the entire state.

Many of the schools on the Navajo and Hopi Reservation are not funded particularly well, which hurts them in teacher recruitment and other areas. The reservation public schools lack the property tax base that suburban schools use to supplement the state and federal funds to provide a better education for their students. But, it can also be argued that when some of the Navajo and Hopi schools get extra money, it is used for interscholastic athletics and other non-academic purposes rather than cutting class sizes so teachers can give students more individual attention or supplying teachers with the materials they need to teach.

From Table III it is apparent that the Indian was achieving at a somewhat lower level than the non-Indian in all subjects and at all grade levels. However, there are some interesting patterns that seem to appear in Table III that should be noted.

The difference in total achievement between the Indian and non-Indian seems to be greater from the 8th grade through the 10th grade than from the third through the seventh grade.

As a whole, both the Indian and non-Indian experience their greatest difficulty in the arithmetic area. Whereas the Indian seems to do best in the language portion of the test, the non-Indian seems to do best in the reading area.

There is the least difference between the Indian and non-Indian in the subject of spelling. Here the Indian comes closest to equaling the work of the non-Indian. The greatest area of difference between the two groups seems to be in the area of arithmetic reasoning and the arithmetic fundamentals.

While the problems are test scores and graduation rates, variables which trigger such outcomes included ill-suited curriculum:

In addition to inappropriate teaching methods, Indian schools are characterized by an inappropriate curriculum that does not reflect the Indian child’s unique cultural background (Coladarci, 1983; Reyhner, in press). Textbooks are not written for Indian students, and thus they enlarge the cultural gap between home and school.

This is a criticism repeated often in discussions concerning indian culture and education. Warren was a self-proclaimed “woman of color” at Harvard with “high cheekbones.” This could have been a cause for her: working with publishers to develop and print curriculum better-suited for indigenous students. (Warren could have worked with schools to replicate the steps of the Cherokee Language Immersion School, which set about improving its educational approach by going charter.)

Warren could have led the effort to combat why, on average, indigenous students score lower than white students on standardized tests.

That Elizabeth Warren exploited the rich history of our Native cultures for personal gain and academic accolades while actual indigenous students struggled is reprehensible. After succeeding in that exploitation and personal gain, Warren refused to give back to the culture she exploited. How much would it have meant to have a real “woman of color,” a real American Indian female educator at Harvard who used her position to bring greater awareness to the educational needs of indigenous Americans?

Instead Elizabeth Warren snubs Cherokee activists when they try to meet with her.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.