Garden Plot: a generic Operations Plan for military support related to domestic civil disturbances.

Like charred fingers clawing skyward, columns of thick black smoke rose from a burning Los Angeles. It was April 30, 1992, and I was flying into Long Beach from the San Francisco Bay area to join my Army National Guard unit to patrol the riot-battered city.

Twenty-four hours before, I was working on a classified missile defense program for Lockheed. My wife and infant daughter had traveled with me and were staying at a nearby Residence Inn. Life was good. Only a year before, I was unemployed–laid-off during a few months of active duty in support of the Gulf War.

I went back to the hotel on the evening of April 29 to the news of the near-beating death of trucker Reginald Denny in the aftermath the acquittal of the four Los Angeles Police Department officers charged with using excessive force during their arrest of Rodney King after a drunken King led them on a high speed chase and then resisted once the police pulled him over. At 9 PM, Governor Pete Wilson called out 2,000 National Guard troops, but my unit, a tank battalion headquartered in National City just south of San Diego, wasn’t among them.

By early morning on the 30th, the violence appeared to have died down. I went to work.

The great InterWeb/Twitter/Facebook complex was as yet unformed. The World Wide Web wouldn’t get its first graphical browser until the following year. Working in the classified security vault, I was clueless about the events that started to spiral out of control 400 miles to south in Los Angeles by mid-morning.

By lunchtime, L.A.’s mayor, Tom Bradley, declared a dusk-to-dawn curfew. A television set was switched on in the program bay where I was working. A colleague walked by and said, “Aren’t you in the National Guard?” then gestured at the TV where images of burning buildings and looters filled the screen.

I called my wife and told her to be prepared to fly by the afternoon. She checked our answering machine at home, but the National Guard hadn’t yet left a phone tree message calling me up to active duty (in 1992, few people had cell phones which were very expensive and as large as walkie-talkies). I called my unit and they said it was very likely we would be activated.

We flew back home that afternoon, Los Angeles burning below us as the sun set over the Pacific.

I grabbed my gear at home and linked up with my National Guard unit at an armory in Long Beach.

We trained for a few hours in the parking lot amidst camouflaged trucks–although the training seemed wholly irrelevant to the mission at hand, since it was geared towards handling a circa 1960s mass demonstration rather than the urban warfare-like environment were about to enter.

Since the Guard had been told by law enforcement not to worry about a civil disturbance associated with the trial verdict, the Guard had loaned some of its riot control equipment to law enforcement. Finally, face shields and flak vests showed up, then the ammunition. The delay in the ammunition was a classic instance of unintended consequences: in a move designed to save money, bureaucratic paperwork, and reduce the threat of terrorists or criminals stealing ammunition and weapons from an armory, all ammunition had been centralized at a base in the middle of the state, some 220 miles away. Without ammo, the Guardsman would have been vulnerable and of questionable effectiveness, given the intensity of the violence. Lastly, as an officer (I was a captain then), I was issued two military-grade tear gas (CS) grenades.

Early in the morning on May 1, we formed into a convoy and made our way to the area that would be our home for the next few days: the Baldwin Hills Crenshaw Plaza at the corner of Crenshaw and Martin Luther King, Jr. Boulevard.

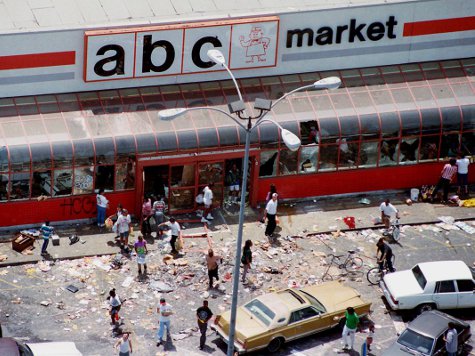

A burning fast food joint greeted us as we pulled onto Crenshaw, a couple of miles from our destination. As I was puzzling over why anyone would bother to burn down a drive-through, a burning car came into view, then another. A small group of looters in a strip mall, intent on increasing their material worth, ignored us as we rumbled by.

As we pulled into the large shopping mall, our advance party was dispersing and arresting a group of about 50 looters. We secured the parking structure. Our command group made its way to the L.A.P.D.’s South L.A. homicide and traffic division office in back of the ground level of the parking garage. The officers there were visibly relieved, saying that an angry mob had formed outside their steel doors just before we arrived.

The police gave us a quick overview of the neighborhood, drawing our attention to the neighborhood to the southwest, off of Santa Rosalia Drive, calling it “The Jungle” for its frequent violence caused, they said, by racial strife between the Mexican-Americans and African-Americans who lived there.

Our armor battalion of about 350 tankers began to send out patrols, sans armor, both mounted and on foot.

Cars were burning everywhere. Looters had stolen cars to use as battering rams to break into liquor stores and electronics shops. People even shot at firefighters who responded to the many fires. Armed escort was needed for the fire trucks.

We learned that armed men on rooftops were the good guys, mostly Korean shop owners protecting their life’s investment. The armed men on the street were the hostiles.

Of the 53 people who were killed during the 1992 L.A. Riots — 19 more than died in the 1965 Watts Riots — two were Asian, and one of those deaths was due to a “friendly fire” incident in which two groups of Korean shop owners mistook the other for looters. Despite their shops and liquor stores being frequently singled out for arson and looting, the Korean immigrants made full use of their uniquely American Second Amendment rights, protecting themselves and their property during a multi-day breakdown in law and order.

As we went out on patrol that day, the residents of the largely middle class African-American neighborhood to the east of the mall called out, “God Bless the National Guard!”

Gang members, up by Noon after a long night of looting, had a different reaction. They threatened our troops, flashing gang signs, thick gold chains hanging off their necks.

Late that afternoon, a stay bullet shattered the back passenger window of a car parked about 30 feet from where I was operating in our battalion HQ.

We found out that President George H.W. Bush was federalizing us, bringing the California National Guard under U.S. government control. The President addressed the nation, saying that he would “use whatever force is necessary” to quell the “random terror and lawlessness.”

Unbeknownst to the California National Guard troops on the scene, Secretary of Defense Cheney had put 4,000 active duty soldiers and Marines on alert the day before.

As night began to fall, I led my first of three foot patrols. I formed up the squad of eight and took point, asking a Vietnam veteran staff sergeant to follow. He had grown up in the neighborhood and, being African-American, I thought he might reduce the tension should we encounter difficulty. As soon as we stepped onto Crenshaw, the sergeant locked and loaded. Instantly, I heard the other troops do the same. I stopped and turned around. “Take the rounds out of your chambers,” I said, “This is America, not Lebanon, if someone takes me out, you’ll have plenty of time to lock and load.” Our orders were to patrol with loaded magazines, but no round in the chamber.

Around midnight, we heard a commotion in “The Jungle.” We jogged over to investigate. It was nothing more than a domestic dispute between a very drunken man and his very irate woman. She kept saying she was going to kill him. I told them that they needed to get off the street–that there was a curfew. She reluctantly headed for home, escorted by a soldier. I asked the man to decamp for home, “But she’ll kill me!” he slurred. I thought, that might be so, but she’ll have to do it in the house, not on the street. We took him home too, after he dumped the rest of his whiskey down the storm drain, a dozen sets of eyes looking down on our squad from the unlit windows of the adjacent two-story apartment.

The next patrol almost turned tragically comic. A shiny all-black sedan slowly rolled towards us, head lights off. It was tricked out with chrome rims and looked like a drug baron’s ride. The windows were part-way down. I deployed the squad into an “L” at the intersection, signaling them to be prepared for what we thought was an attempted drive-by gang shooting. I shouted out, “Halt! There’s a curfew. What’s your business?” The car lurched to a halt. I could see frenzied activity in the unlit car. Then a high-pitched, somewhat cracking voice, said from the driver’s side, “L.A.P.D. vice squad!” A hand extended police ID. I was incredulous. The vice squad was patrolling at night in a darkened, unmarked car as buildings still burned and thousands of nervous Guardsmen patrolled the streets they were unable to control.

By May 2, I had been awake for more than 36 hours straight, patrolling on foot and on the back of trucks and HUMVEEs.

It was then that we learned that federal troops were arriving and would take over command of the operation. Our morale plummeted–especially as we had quelled the violence within 24 hours of our arrival in the city and saw little need for the active duty to “save the day.” Further, with more advance notice, the 1,500 U.S. Marines and 2,000 U.S. Army soldiers took longer to muster into L.A. than did 10,000 Guard members, a force of citizen-soldiers launching into action with no advance warning. Hours later, the 7th Infantry Division commander assumed command of the joint U.S. Army-U.S. Marine Corps force, placing the National Guard commanding general in charge of all Army forces, both Guard and Active Duty, our honor restored, morale bounced back.

Since National Guard members usually operate under control of their respective governors in peacetime, the Posse Comitatus Act restrictions against federal troops assisting in civilian law enforcement duties doesn’t apply to them. That changed on May 2, however, when the military lawyers from the 7th Infantry Division mistakenly thought that the Guard’s federalization compelled us to act within the confines of Posse Comitatus. Immediately, our close cooperation with the L.A.P.D. was scaled back by the active duty general.

In fact, when President Bush signed Executive Order 12804 on May 1, invoking the Insurrection Act, he authorized the Army and Marines, as well as the federalized National Guard, to enforce civilian law to help restore law and order. Had Wikipedia been available in 1992, the 7th Infantry Division JAG officers (military lawyers) might have come to a different conclusion.

Flyers urging violence against law enforcement in service of the “insurrection” were commonplace during the riots. The flyers were written and printed by Communist organizations–which seemed ironic, given the fall of the Berlin Wall only two-and-a-half years before. Strangely enough, the El Salvadoran Communist guerilla group FMLN (Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front) has an ongoing presence in Los Angeles, where they participate in the city’s annual May Day parade, carrying their red banners.

On May 3, with the military taking a lower profile, gang members began to show more defiance. Rumors were flying around that the military had no ammunition or wasn’t allowed to shoot. We were very concerned about what might happen the next night when Mayor Tom Bradley was expected to lift the nighttime curfew.

As fate would have it, a gang member wannabe tried to run over a team of Guardsmen at a checkpoint. On his third pass to try to kill the soldiers, they fired 10 rounds at the tires of the onrushing car. He pressed on towards the checkpoint. So, the soldiers shifted fire, killing him with two bullets to the head and one in the shoulder.

The next morning, the gang members wouldn’t even look us in the eye as we made a limited number of patrols. They knew the Guard could shoot to kill.

During the far less destructive Watts Riots in 1965, a considerable amount of ammunition was expended, up to and including .50 caliber heavy machine gun rounds. In the 1992 riots, the National Guard only fired 20 rounds – a remarkable affirmation of restraint and training.

People opined that the riots in 1992 were entirely predictable, when looking at the area’s recession-time high unemployment and poverty rate of between 20 and 40 percent. Today, South Los Angeles (formerly known as South-Central Los Angeles) has a poverty rate of 30 percent, about the same as in 1992. The area’s demographics have shifted significantly, however, moving from Hispanics, mainly Mexican-Americans and African Americans comprising 47 percent each in 1990 to today, wherein Latinos outnumber blacks two to one.

There are two valuable lessons from the 1992 Los Angeles riots. First, civilization has a very, very thin veneer that can break down suddenly and with little warning (there were sympathy riots up and down the West Coast and unrest in other urban areas). Second, when civilization does break down, law enforcement is virtually powerless for a time during which a judicious exercise of one’s Second Amendment rights may be all that stands between you and destructive anarchy.

For a live Twitter feed that recreates the time line of the L.A. Riots, see: @RealTimeLARiots.

Captain DeVore on a pile of rubble a few days after the riot started (you can tell because the boots are shiny and the rubble has stopped smoking, also, no tear gas grenades).

FMLN communist marchers in the 2010 Los Angeles May Day parade.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.