CARACAS, Venezuela (AP) — Oncologist Gabriel Romero performs hundreds of life-saving surgeries a year, but he no longer takes pleasure in his work.

That’s because he believes that many of the mastectomies he does on some of Venezuela’s poorest women wouldn’t be needed in a normally functioning country. Doctors say they are being forced to return to outdated treatments because the socialist country’s economic problems make it impossible to ensure the proper running of radiation machines in public hospitals, where patients receive free treatment under Venezuela’s universal health care.

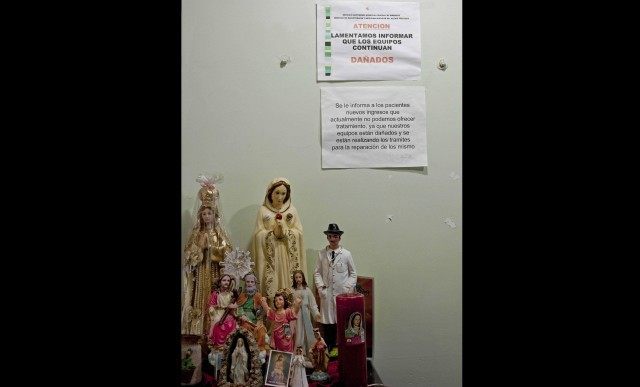

“You don’t feel comfortable with it, because you’re making a decision that goes against your professional judgment,” Romero said recently after seeing patients in the grubby basement clinic at the Dr. Luis Razetti Oncology Center, at the foot of a Caracas slum. The hospital’s only linear accelerator machine, the more modern of the two kinds of radiotherapy devices used in Venezuela, has been broken since November.

“We’re practicing medicine from the 1940s here, and we know that’s not right,” Romero said.

The challenges facing doctors are just one reflection of an economy battered by widespread shortages. The recent crash in global oil prices, which account for 95 percent of Venezuela’s exports, is creating a cash shortage that makes it difficult to buy imported goods, such as parts for medical machines. Also depressing economic activity is 68 percent inflation and a currency crisis that has seen the value of the local Bolivar plunge 46 percent this year on the closely-watched black market.

Mastectomies were once the go-to procedure for women with breast tumors, but doctors now favor radiation treatment paired with less invasive surgeries that leave some of the breast intact. Only about a third of breast cancer patients in the U.S. who are treated with surgery undergo some kind of mastectomy, according to the American College of Surgeons.

But in Venezuela, doctors are increasingly resorting to an extreme form of mastectomy that removes not just the breast, but also lymph nodes and the underlying chest wall muscle. More than half of the several dozen radiotherapy machines in public hospitals are broken, according to the country’s medical federation. The government, which controls access to foreign currency, is not providing repair companies with the cash to import the parts to fix them.

“It doesn’t make you feel good,” said Gerardo Hernandez, former president of the Venezuela Cancer Society. “But for breast tumors, without the option of radiation, it would be irresponsible not to do a mastectomy.”

No data was available from professional organizations or government sources about the number of mastectomies performed in Venezuela, and the Health Ministry did not respond to repeated interview requests. Romero estimates that at the clinic where he works, about 70 percent of all patients now undergo modified radical mastectomies.

It’s not just oncologists. Other specialists also say Venezuela’s shortages are forcing them to practice a more old-fashioned kind of medicine, including conducting coronary bypass surgeries for cardiac patients instead of using scarce heart stents to open up clogged arteries.

Government backers blame medical supply companies for the shortages, and accuse them of hoarding scarce materials. Detractors say the situation is part of the general collapse of the economy brought about by an administration that will not allocate dollars where they’re needed.

The Venezuelan medical supply association sent a letter to Congress in March advising that the government approved just $250 million in foreign currency for medical supplies last year, well short of the $1 billion needed, and has not made any approvals this year. The government outfits public hospitals in part with medical supplies from the group.

Retiree Ana Mercedes, who had a radical mastectomy at Luis Razetti hospital, says that six months later she still can’t trust her swollen arms to pick up a glass of water. Mercedes lives a three-hour drive away from the Venezuelan capital and came to Caracas for treatment.

Her doctors said saving the breast wasn’t an option and recommended a mastectomy and radiation. But the machine for her treatment gave out midway through the prescribed sessions.

“People don’t understand how serious the surgery is,” she said while waiting for a follow-up appointment in Caracas. “But having to rely on the radiation machines is worse. I was so terrified that something would start growing again.”

Venezuela has seen one of the steepest increases in breast cancer mortality in Latin America, according to a report sponsored by the Pan American Health Organization.

The company under contract to maintain most of Venezuela’s linear accelerators— machines popularized in the 1980s that generate beams of high-energy radiation— hasn’t been able to import anything since October, because the government hasn’t approved the firm’s access to foreign currency, said Antonio Orlando, president of the medical equipment firm Meditron.

“We’re completely paralyzed,” Orlando said, adding that his company gets calls daily from worried patients. “It does make me feel bad; we’re talking about cancer patients here.”

___

Follow Hannah Dreier on Twitter: https://twitter.com/hannahdreier

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.