In her store located a stone’s throw from the wall separating the United States and Mexico, Ida Pedrego sighs at the thought of White House hopefuls visiting the border to talk about immigration.

Last month, she saw Democrat Kamala Harris arrive in Douglas for a photo op at the looming metal barrier and then a speech in a nearby building.

The month before, Donald Trump was about an hour’s drive away, holding forth about what a disaster he thinks the situation is.

“The problem is… they come and they’re here for a few minutes,” the 72-year-old told AFP.

“What can you see? What can you learn in such a fast time?”

Immigration is repeatedly cited as a major issue for voters ahead of next month’s presidential election.

But of the seven swing states expected to decide who gets the keys to the White House, only Arizona has a border with Mexico.

That means it gets a lot of attention from the candidates and their surrogates.

For Pedrego, a Democrat, the attention — and the misrepresentation she feels she hears from Trump — is tiring.

His apocalyptic vision of a country overwhelmed by hordes of the insane and the unrelentingly criminal, where unsanctioned foreigners wreak violence on a cowering population, is utterly unrecognizable to her.

“Douglas is one of the safest communities,” she says, noting that violent crime is a rarity and there is so little petty theft that she doesn’t even lock her car.

The town’s Republican mayor, Donald Huish, agrees.

“We don’t have the crime that people seem to think is associated with living on the border,” he says.

“That’s not true. It’s totally not true.”

Huish, who describes himself as “an old school Republican,” says neither side of the political debate takes the issue of the border seriously.

Trump’s inflammatory sensationalism — with his talk of immigrants eating people’s pets — is no better than what he considers the Democratic Party’s laissez-faire talk of decriminalizing illegal crossings.

“People don’t understand the border,” says the 65-year-old Huish, a native of Douglas.

‘Frustrating’

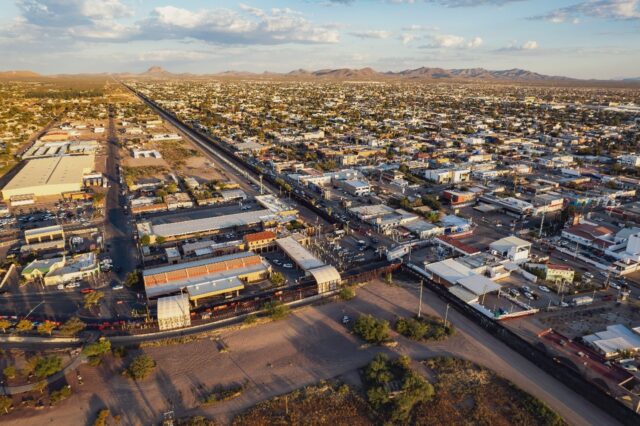

In this dusty town of 16,000, Spanish jumbles freely with English in the restaurants, bars and stores.

Many here have family in Agua Prieta, a 100,000-strong city on the other side of the wall, whose factories and economic dynamism are crucial to the lifeblood of Douglas.

The record influx of migrants recorded under President Joe Biden was not felt in Douglas for a long time, but when they began arriving last winter, the city organized itself.

Migrants were housed in a church, or transferred by bus each day to somewhere else in the United States.

Between September and March, Douglas saw 8,400 people pass through.

Dealing with them stretched the border police force, which usually dedicates itself to the fight against drug trafficking — a problem that has beset the town for decades.

Huish says he wants more resources to tackle the scourge — like those promised in the bipartisan immigration bill that Congress drafted in the spring, which Democrats say Trump sank because he did not want the problem fixed before the election.

“It’s frustrating,” the mayor says.

Immigration is being used like “a political football” that the parties are passing back and forth, he says.

“I wish somebody would just stop and bring out the (video replay) and look at the situation and see what’s best.”

– Deadly consequences –

During her visit to Douglas, Harris said she would resurrect the bipartisan bill if she wins, and would maintain an executive order issued by Biden that has largely shut off the flow of migrants.

But like many Republicans, Timm Klump has no confidence in the vice president.

On his ranch that abuts the border, flood gates designed to protect the land in the event of heavy rainfall have been left open since 2021, he says, allowing anyone to just wander across from Mexico.

“I think it says like, ‘hey, the previous administration built a wall, we’re not maintaining it. We just want to destroy what they did, come in as much as you want’,” he says.

The 35-year-old rancher says he often comes across thirsty migrants on his land. Occasionally, he finds their desiccated corpses.

People who have died in the desert are honored every Tuesday at a vigil in Douglas, with dozens of white crosses placed on the sidewalk.

The crosses are tended by Mark Adams of the Frontera de Cristo, a Presbyterian ministry that works on both sides of the border.

In the 25 years he has been helping migrants in Douglas, Adams says he has seen the wall grow a little in some way under each president.

But the problems continue.

At fault, he says, is Congress, which for decades has refused to take on the difficult but vital issue of immigration reform, which needs to go hand-in-hand with border security.

Without one, you’ll never have the other, Adams says.

“Instead of addressing the root causes of the realities of migration… we’ve continued a policy that has led to death,” he says.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.