KABUL, Afghanistan (AP) — Threatening letters from the Taliban, once tantamount to a death sentence, are now being forged and sold to Afghans who want to start a new life in Europe.

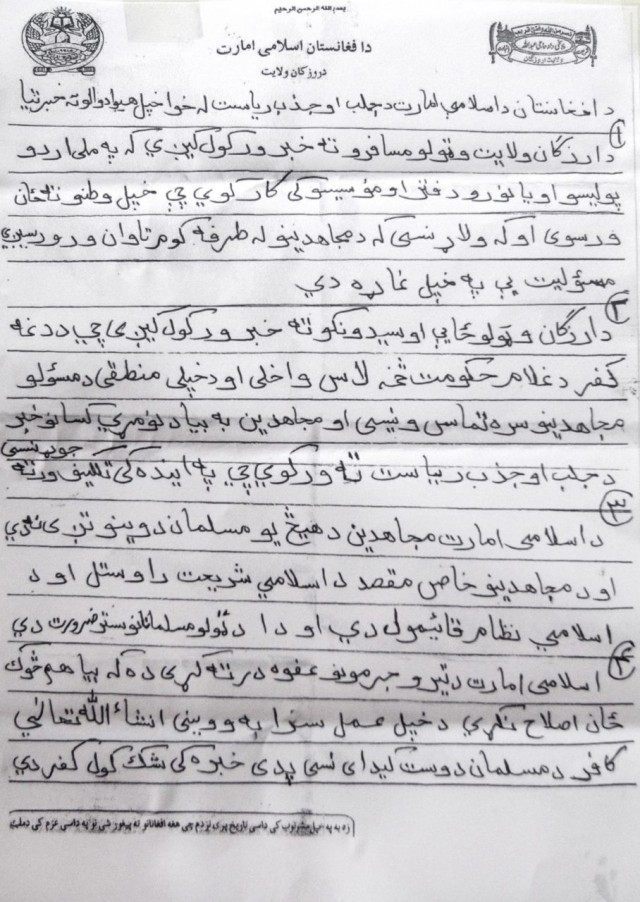

The handwritten notes on the stationery of the so-called Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan were traditionally sent to those alleged to have worked with Afghan security forces or U.S.-led troops, listing their “crimes” and warning that a “military commission” would decide on their punishment. They would close with the mafia-style caveat that insurgents “will take no further responsibility for what happens in the future.”

But nowadays the Taliban say they have mostly ceased the practice, while those selling forged threat letters are doing a brisk business as tens of thousands of Afghans flee to Europe, hoping to claim asylum. Forgers say a convincing threat letter can go for up to $1,000.

“Of the threat letters now being presented to European authorities by Afghans, I’d say only one percent are real and 99 percent are phony,” said Mukhamil, 35, who has forged and sold 20 such letters. Like many Afghans, he has only one name.

He sticks to a simple formula — accusing the buyer of working for Afghan or U.S. forces — and adds a Taliban logo copied from their website.

“To this day I have only ever known one guy who genuinely got a threat letter from the Taliban. All the rest are fake,” he said.

There is no shortage of customers. With unemployment at 24 percent and the insurgency raging across much of the country, the government expects that 160,000 Afghans will have left by the end of the year, four times the number of departures in 2013.

Germany is struggling to accommodate hundreds of thousands of refugees, but has said economic migrants must return to their home countries. Last month, Germany’s top security official complained of an “unacceptable” influx of Afghans from relatively safe areas of the country. Germany, a longtime contributor to international forces in Afghanistan, currently has more than 900 soldiers in the NATO-led training mission there.

Germany’s Federal Office for Migration and Refugees said it was aware of the letters but that no statistics are kept on them. Spokeswoman Susanne Eikemeier said that since such letters are not official documents, the weight granted to them is generally limited.

“Such documents are assessed in the context of examining the credibility of the overall account of the applicant,” said Eikemeier. “While they can be drawn on as evidence of a threat by the Taliban, the applicant’s entire account has to be coherent, comprehensible and credible.”

Even the Taliban, who have stepped up their 14-year insurgency in recent months and spread to new areas, say most of the threatening letters are forgeries.

Taliban spokesman Zabiullah Mujahid said that when fighters suspect someone is working with the government or security forces, they contact the person’s relatives to request that he stop. “We don’t send threat letters, that’s not our style. Only very rarely would we use the phone, in cases where we perceive serious problems,” he said.

“All these so-called Taliban threat letters are fake,” he added, reeling off a list of people who he says falsely claimed to have received threatening letters from the Taliban. “We are trying to provide a good environment for our youth to remain in their country,” he added.

An official at Afghanistan’s intelligence agency, the National Directorate of Security, also dismissed the letters, saying it was clear many people were buying them to strengthen their case for asylum. No one has been arrested in connection with the forgeries.

“The government does not believe it is worth our effort to go after the people making or buying them. We concentrate our efforts on people who receive genuine threats,” he said. The official was not authorized to speak to media so spoke on condition of anonymity.

The Taliban have a long history of threatening Afghans, and their brief seizure of the northern city of Kunduz earlier this year offered a brutal glimpse of what could await the country if they return to power. The group issued clear threats, not only against those working with the government, but journalists and women’s rights activists. The U.N. estimated that half the city’s population of 300,000 residents fled the takeover.

Gul Mohammad, 28, said the Taliban came to his home and accused him of being a spy because he worked as a security guard for an international charity in Kunduz. The militants tried to force their way into the house, but when his father resisted, they stole two of the family’s cars instead, he said.

Government forces drove the Taliban out of Kunduz in a two-week operation, but the insurgents still control a number of rural districts scattered across the country. Fear of the Taliban is a key factor driving the country’s exodus, even if many of those leaving have not received personal threats.

Hazrat Gul, 25, made it to Italy more than three years ago with a fake Taliban threat letter, saying it helped him to successfully claim asylum along with his wife and their three children. But while it worked for him, Gul said it is becoming well-known in Europe that most letters are fake.

“It is rare these days for European courts to accept these letters, as the word is out that you can buy them in shops in Afghanistan,” he said.

___

Associated Press writer Frank Jordans in Berlin contributed to this report.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.