The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ), the group behind the “Panama Papers” leak of financial data five years ago, released a sequel of sorts on Sunday. Dubbed the “Pandora Papers,” the new trove of leaked confidential financial documents suggests dozens of world leaders and hundreds of public officials are stashing large sums of money in hidden bank accounts and secret investment projects.

The Pandora Papers leak includes almost 12 million documents, weighing in at 2.94 terabytes of data, harvested through undisclosed methods from 14 financial services providers. Most of the information was dated between 1996 and 2020, although some older records dating back to the 1970s were included as well.

ICIJ noted that by contrast, the Panama Papers came from a single provider, the Mossack Fonseca law firm, and was only about half as big as the Pandora trove. Some of the same corporate entities exposed in the Panama Papers leak also appear in the Pandora Papers, some of them using new identities or registrations.

The documents “cover a wide range of matters,” from establishing shell companies and trusts to buying luxury goods and planning estates. ICIJ claimed some of the documents are “tied to financial crimes, including money laundering.”

ICIJ said over 600 journalists from 150 media outlets in 117 countries participated in analyzing the leaked documents, making it the largest journalistic collaboration in history.

The papers name over 330 politicians, plus “celebrities, fraudsters, drug dealers, royal family members and leaders of religious groups around the world.”

The authors said smaller individuals and entities exposed by the leak, including “small business owners, doctors and other, usually affluent, individuals away from the public spotlight,” were excised from the report to preserve their confidentiality because they “don’t represent a public interest.”

“ICIJ matched Forbes’s billionaires lists against the Pandora Papers to find more than 130 who had entities in secrecy jurisdictions. More than 100 of them had a combined fortune valued at more than $600 billion in 2021,” the report said.

International media organizations reporting on the Pandora Papers leak, such as Reuters on Monday, noted they could not “independently verify the reports or the documents detailed by the consortium.”

“The use of off-shore companies is not illegal or by itself evidence of wrongdoing, but news organizations in the consortium said such transactions could be used to hide wealth from tax collectors and other authorities,” Reuters observed.

One of the marquee names appearing in the initial Pandora Papers leak is King Abdullah of Jordan. The papers showed the king spending some $106 million to buy luxury homes on the Pacific Coast of the United States.

The Jordanian Royal Palace responded to the report on Monday by stating there was nothing “unusual or improper” about King Abdullah’s real estate purchases, which it said were made with his own money, not funds from the government treasury.

“These properties are not publicized out of security and privacy concerns, and not out of secrecy or an attempt to hide them, as these reports have claimed,” the Royal Palace stated.

“Many Jordanians were quick to defend the king, calling the accusations defamation of the monarch. Others derided him over reports that he spent more than $100 million on properties through offshore companies at a time when aid was flowing into his country,” observed the Washington Post, which participated in the Pandora project.

Jordanian nerves may also be a little raw after the unusual palace drama of April 2021, when the king’s half-brother, Crown Prince Hamza bin Hussein, was accused of conspiring with “foreign parties” to destabilize the government. Some of Hamza’s complaints against the monarchy involved corruption.

Jordan’s King Abdullah II and Crown Prince Hussein (R) arrive for the opening session of the fourth ordinary parliamentary session in the capital Amman on November 10, 2019. (Photo by KHALIL MAZRAAWI/AFP via Getty Images)

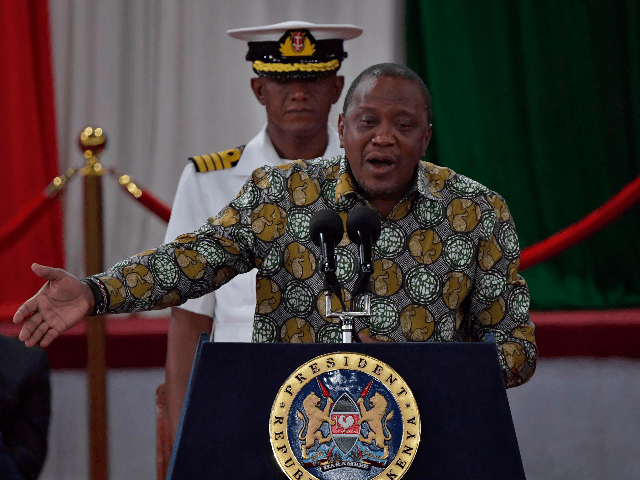

Another notable name was Uhuru Kenyatta, the president of Kenya. According to the Pandora Papers, Kenyatta’s family has half a billion dollars tucked away in offshore foundations, shell companies, and tax havens, administered by Swiss bankers.

Kenya’s President, Uhuru Kenyatta gives an address on November 27, 2019, during the launch of the Building Bridges Initiative (BBI) report in Nairobi. (Photo by TONY KARUMBA/AFP via Getty Images)

Kenyatta billed himself as an anti-corruption crusader during his 2013 presidential election campaign, and as ICIJ sourly noted, he used his last State of the Nation address to “acknowledge that too many Kenyans live in poverty and too many officials loot the country’s public resources.”

The BBC quoted Kenyatta claiming in 2018 that all of his family’s holdings were “open to the public” and duly declared to the proper Kenyan regulatory authorities. According to the BBC, Kenyatta is currently traveling abroad on state business, and plans to “respond comprehensively” to the Pandora Papers when he returns.

The report accused a number of individuals linked to Russian President Vladimir Putin of concealing their wealth, at the lower end including a woman named Svetlana Krivonogikh who acquired an apartment in Monaco through a Caribbean company in 2003. The Pandora Papers strongly implied Krivonogikh was Putin’s mistress and the child born shortly after the purchase of the apartment was Putin’s daughter.

The Kremlin dismissed all of the ICIJ’s implications and allegations on Monday, describing the information as unverified and demanding more concrete evidence of wrongdoing before any action could be taken.

“For now it is just not clear what this information is and what it is about. If there are serious publications that are based on something concrete and refer to something specific, then we will read them with interest,” said Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov.

“Honestly speaking, we didn’t see any hidden wealth of Putin’s inner circle in there,” Peskov added.

Russian President Vladimir Putin gestures while speaking at the annual meeting of the Valdai Discussion Club via video conference at the Novo-Ogaryovo residence outside Moscow, Russia, Thursday, Oct. 22, 2020. (Alexei Druzhinin, Sputnik, Kremlin Pool Photo via AP)

On the other hand, Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan “welcomed” the revelations and vowed on Monday to investigate all of the dubious financial arrangements exposed by the Pandora Papers and take action if illegal activity was confirmed.

Over 700 Pakistanis were named in the leaked documents, including finance minister Shaukat Tarin, whose family apparently owns four offshore companies, and water minister Chaudhry Moonis Elahi, who allegedly “pulled out of making planned investments through offshore tax havens after he was warned the investment would be reported to the country’s tax authorities.”

Prime Minister Andrej Babis of the Czech Republic was accused in the report of using shell companies to buy a $22 million chateau near Cannes, France in 2009.

Czech police immediately stated they would take the allegations seriously and fully investigate “all citizens of the Czech Republic who are mentioned” in the papers.

Babis, in turn, claimed the document dump was a scurrilous effort to “influence the Czech election,” which will be held this week, and insisted he has done nothing “illegal or wrong.”

“I paid all the taxes. This is completely absurd. The money was sent from a Czech bank; it was my money, it was taxed, and then it came back to a Czech bank,” Babis complained in a TV interview on Sunday.

The UK Guardian noted Babis already faces a “mounting list of controversies” going into the election, including allegations of fraudulently obtaining millions of dollars in European Union funds to construct a hotel. These scandals were serious enough to make the EU threaten to suspend subsidy payments to the Czech Republic.

Former British Prime Minister Tony Blair and his wife Cherie appear in the Pandora Papers, having allegedly used an offshore company to avoid paying about $425,000 in taxes on an expensive London townhouse in 2017. The Blairs rejected the allegations on Monday and insisted they have “never used offshore schemes either to hide transactions or avoid tax.”

NEW YORK, NY – SEPTEMBER 11: Tony Blair attends the Annual Charity Day hosted by Cantor Fitzgerald, BGC and GFI at Cantor Fitzgerald on September 11, 2018 in New York City. (Photo by Noam Galai/Getty Images for Cantor Fitzgerald)

The ICIJ criticized financial providers for turning blind eyes to suspicious transactions from powerful politicians and billionaires – including U.S. companies that did business with foreign nationals exposed in the Pandora leak, although none of the purportedly corrupt politicians and oligarchs exposed by the leak were themselves Americans.

An early reaction from observers such as Oxfam International, a prominent charity organization, was that so many world leaders are busy making extravagant purchases and hiding vast troves of personal wealth while their countries are wrestling with underfunded social services or receiving international aid.

“This is where our missing hospitals are. This is where the pay-packets sit of all the extra teachers and firefighters and public servants we need. Whenever a politician or business leader claims there is ‘no money’ to pay for climate damage and innovation, for more and better jobs, for a fair post-COVID recovery, for more overseas aid, they know where to look,” Oxfam complained.

“Tax havens cost governments around the world $427 billion each year. That is the equivalent of a nurse’s yearly salary every second of every hour, every day. Ordinary taxpayers have to pick up the pieces. Developing countries are being hardest hit, proportionately. Corporations and the wealthiest individuals that use tax havens are outcompeting those who don’t. Tax havens also help crime and corruption to flourish,” Oxfam said.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.