An “emergency ordinance” against “wholly or partly false” news content related to the coronavirus pandemic went into effect in Malaysia on Friday, prompting criticism from opposition politicians and international free speech activists.

Violators of the ordinance face heavy fines and up to six years in prison.

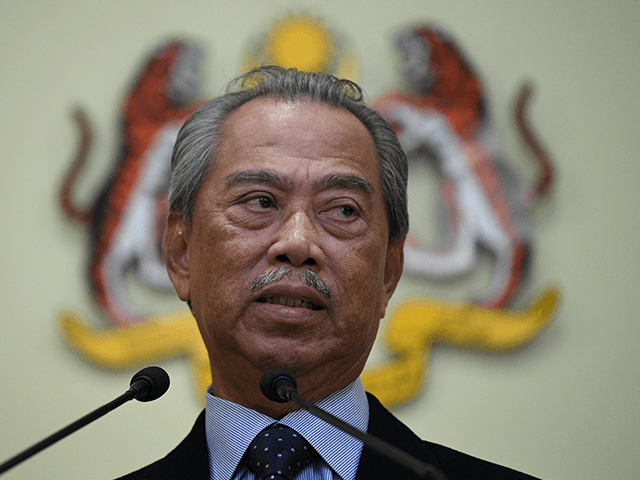

On the same day, Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin’s office issued a government circular “prohibiting civil servants from making negative public statements, or sharing or distributing any content deemed detrimental to government policies or its image,” Reuters reported.

These actions fueled fresh accusations that Yassin’s government is exploiting the coronavirus pandemic to silence dissent and consolidate political power. Sadly, Malaysia’s is far from the only government accused of exploiting the pandemic for political gain.

“Our interest is in fighting COVID-19 [Chinese coronavirus] and we will do whatever it takes,” insisted Communications Minister Saifuddin Abdullah in defense of the ordinance. “We take cognizance of the fact that we have to be fair, we have to be just in carrying out our duties.”

Abdullah gained international notoriety in July 2020 for a failed effort to regulate all social media videos by requiring their creators to obtain the same licenses needed by a full-blown documentary film production. This would have required every user of Instagram, YouTube, and TikTok to fork over thousands of dollars in fees whenever they decided to upload a short video clip.

The fine for spreading fake coronavirus news can be up to 100,000 ringgit, or about $24,000, which is close to the average annual income in Malaysia. The ordinance also allows the police to take all “necessary measures” to remove misinformation, including additional fines for users who refuse to give their passwords and data encryption codes to the police on demand.

Critics noted the ordinance was shoved through as an “emergency” measure, so it was not debated or approved by the Malaysian parliament, and it does little to define exactly what constitutes “fake news” about the pandemic. The police were also empowered to investigate suspected fake news purveyors located outside of Malaysia, even if they are not Malaysian citizens.

“We anticipate further surveillances and invasions of our privacy, arbitrary censorships of critical and dissenting media reports, and thus, attacks on media freedom, and disproportionate crackdowns on legitimate speech,” warned Center for Independent Journalism director Wathshlah Naidu.

Yassin probably would not have been able to get his media restrictions through the Malaysian parliament, as he enjoys only a thin majority and was not actually elected to the office of prime minister – he was selected by King Al-Sultan Abdullah in February 2020 after Prime Minister Mahathir Mohammad resigned suddenly.

Yassin has been perpetually nervous about losing power ever since, an anxiety he alleviates by insisting elections could not possibly be held until the coronavirus emergency is over. By an interesting coincidence, one form of speech punishable under the new emergency ordinance is criticism of the state of emergency, and one provision of the state of emergency was the suspension of parliament, so challenging Yassin’s power in any way has become effectively illegal in Malaysia.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.