Experts are “stumped” and “perplexed” by the dramatic decline in Indian coronavirus cases, which began in September 2020 for no obvious single reason, cutting daily coronavirus cases by almost 90 percent as of February 2021 the Associated Press (AP) wrote Tuesday.

India logged 100,000 coronavirus infections per day at its peak, a caseload that threatened to overwhelm the country’s health care system, but now it has only 11,000 cases per day.

Theories for the sharp decline range from the development of “herd immunity,” or the spread of Chinese coronavirus topping out because many Indians have “some pre-existing protection from the virus,” to unexpectedly high levels of success from social distancing practices or masking.

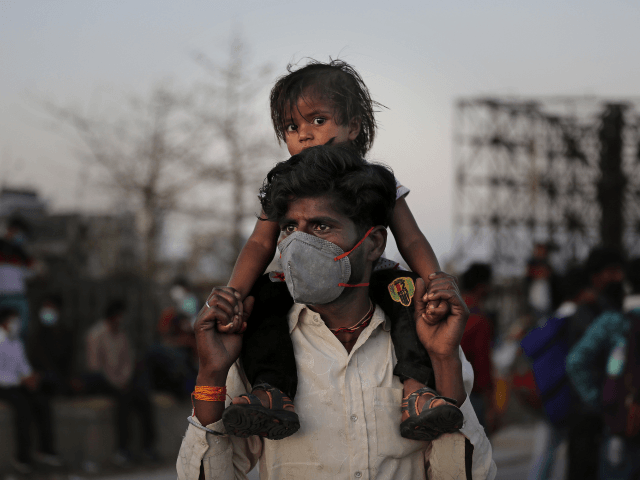

On the latter hypothesis, the AP noted, “the decline is uniform even though mask compliance is flagging in some areas.” NPR saluted India for having an exceptionally aggressive compliance program — so aggressive that when Indians make phone calls, they hear lectures about washing their hands and wearing masks instead of dial tones. This purportedly brought mask compliance up to 95 percent in July, but the decline in cases did not begin until September.

Experts ruled out vaccinations as the primary cause of the decline since the steep downward trend began in September but inoculations did not begin until January.

Herd immunity is also questionable as an explanation because the estimated number of Indians who have been exposed to the coronavirus remains well below the most generous estimates of the percentage necessary before the herd response could stamp a virus out.

A modified version of herd immunity theory holds that Indian cities are so densely populated that they have reached the threshold, while the virus is spreading more slowly or stalling out in rural areas, which feature lower population densities and better-ventilated homes. India’s rural population has less direct contact with city dwellers than in most other large countries, and the country folk spend a great deal of their time outdoors.

NPR pointed to research that found Indians who contract Chinese coronavirus generally seem to be less contagious than most other demographics. Some scientists think India’s warm climate accounts for the slower spread of the disease, although others think India’s climate and air pollution should be making the pandemic worse.

Among other theories for the decline are that Indians could have exceptionally tough immune systems because much of the population has been exposed to epidemics like malaria and cholera that are largely unknown to Westerners; they might even have stronger immune systems thanks to the poor quality of their air and water.

The AP suggested the decline of Indian coronavirus cases does not appear to be a purely statistical artifact, or a result of India counting infections differently, because hospitals have reported a correspondingly steep decrease in demand for intensive care beds and ventilators.

The BBC added Tuesday that India’s dramatic decline in coronavirus cases “is not because of lower testing,” although the tests could be missing some asymptomatic carriers, and the overall downward trend continued in spite of “short and fierce spikes of infections in cities like Delhi.” Delhi reported zero coronavirus deaths for the first time in ten months Tuesday. Over half of India’s states also reported zero fatalities.

“India imposed a sweeping, early shutdown in late March to halt the spread of the virus. Scientists believe that the shutdown, which stretched to nearly 70 days, did prevent a lot of infections and deaths,” the BBC postulated.

As with health experts in other countries, Indian doctors are reportedly concerned about encountering coronavirus variants that prove resistant to the current vaccines. They also worry that people who developed some resistance to the coronavirus might be more vulnerable to the new strains. A particular region of concern is the southern Indian state of Kerala, which looked to be doing well against the coronavirus until recently, but now accounts for almost half of all new infections.

“With the reasons behind India’s success unclear, experts are concerned that people will let down their guard. Large parts of India have already returned to normal life. In many cities, markets are heaving, roads are crowded, and restaurants nearly full,” the AP reported.

Public health experts in other countries are keenly interested in learning why India’s infection rates dropped so steeply, hoping to draw some conclusions that could help other nations control their own epidemics.