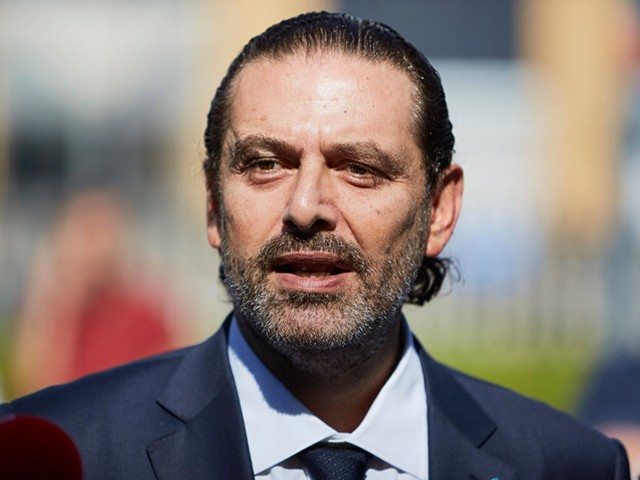

Saad Hariri was designated as the next prime minister of Lebanon on Thursday, his fourth time at bat since 2009 — The previous prime minister-designate, Moustapha Adib, resigned on September 27, barely a month after receiving his appointment.

The prime minister before Adib, Hassan Diab, resigned along with most of the Lebanese government after the gigantic explosion at the Port of Beirut in early August.

Hariri enjoyed the support of his own party, the Future Movement, plus Druze heavyweight Walid Jumblatt and the Shiite Muslim party called Amal. Amal is normally aligned with the terrorist organization/political party Hezbollah, which announced that it would “contribute to maintain the positive climate” but did not openly support Hariri or nominate its own candidate. Hariri is a Sunni Muslim, which is a requirement for serving as prime minister under Lebanon’s unique factional system.

A few other key voting blocs sat this particular nomination out, including the big Christian groups, and the party headed by the son-in-law of President Michel Aoun. Reuters quoted observers who took this as a sign the Lebanese political establishment knows the electorate is deeply frustrated with it.

CNN and the New York Times, on the other hand, interpreted Hariri’s appointment as the Lebanese elite quite literally giving the public more of the same, tapping a politician who has already held the office three times before, and the protest-weary public grudgingly accepting the return of a prime minister it booted out of office in a popular uprising last year.

“Hariri won’t be the best option, but I would say better to be half-blind than fully blind. This country is falling below hell,” one Beirut resident told the New York Times.

“Hariri’s return is the peak of the counter-revolution,” disgruntled political activist Nizar Hassan complained to Al Jazeera News. “A pillar of the political establishment, a multi-millionaire who represents the banks and foreign interests, and a symbol of inefficient governance and widespread corruption: He represents everything we revolted against.”

Hassan thought it might be “more worthwhile to work internally on strengthening our movement” than protesting against Hariri’s appointment, although Al Jazeera noted there was a significant clash on Wednesday between Hariri supporters and anti-establishment protesters in Beirut, concluding with the pro-Hariri forces symbolically burning the clenched-fist icon of the Lebanese protest movement. The anti-establishment protesters proceeded to build even bigger clenched-fist totems to demonstrate their resilience.

Hariri presented himself as the only candidate who could assemble a government quickly enough to avert political and economic doom.

“I tell the Lebanese people, who are facing despairing hardships, I say that I am dedicated to my promise to them to work on stopping the collapse that is threatening our economy, our security, and to rebuild the destruction of the terrible port explosion in Beirut,” he said, vowing to assemble a technocratic administration that could rise above Lebanon’s vicious factional power struggles.

“This is the only and last opportunity for our beloved country,” he warned on Thursday.

Hariri expressly promised to implement reforms desired by Lebanon’s patrons in France, saluting the efforts of French President Emmanuel Macron to deliver humanitarian aid and financial relief in the wake of the Beirut port explosion. Macron was furious when Hariri’s predecessor Adib resigned, saying Lebanon’s feuding parties and interest groups prevented him from forming a government.

Skeptics noted Hariri won even fewer votes in parliament than his two short-lived predecessors and said his ties to the banking industry made it unlikely he would implement the dramatic financial reforms Lebanon needs.

“For whom will he be working and serving? I think he will serve in particular the banks and richer segments of society and the political parties,” Lebanese Center for Policy Studies director Sami Atallah told Al Jazeera.

The Wall Street Journal (WSJ) wondered if Hariri would be able to reassure exasperated international supporters who “have become wary of investing political and financial capital in Lebanon with little or nothing to show for it.”

For that matter, the WSJ warned a growing number of Lebanese are “struggling to adjust to a new economic reality” and “seeking to bail out of the country.”

The government’s absolute inability to hold anyone accountable for the massive explosion that shocked the world three months ago threatens to destroy what little faith remains for the system, both domestically and abroad; inflation is now over 460 percent; banks are locking depositors out of their accounts; crucial subsidies for food, medicine, and fuel may soon expire; and the Wuhan coronavirus is adding its customary share of fear and misery to the dismal situation.

The UK Guardian glumly noted that Hariri was swept out of office by protesters a year ago because he tried to recapture lost revenues for the faltering government — and the Lebanese economy is now much worse than it was then. A fresh attempt to claw back revenue could trigger a civil war, but if Hariri does not shore up the government’s finances, the collapse of food and fuel subsidies could unleash panic-buying, hoarding, and absolute chaos.

Hariri’s resignation before that, in 2017, was widely seen as forced by Saudi Arabia, which invited him to a meeting in Riyadh and did not let him leave until France got involved. Tensions between Saudi Arabia, the United States, and Iran over Lebanon have only increased since then. A major political crisis nearly erupted in Lebanon in August when a United Nations tribunal found an operative of Iran-backed Hezbollah guilty for the 2005 assassination of Saad Hariri’s father Rafik Hariri, but acquitted three other defendants and held Hezbollah itself blameless for the murder.